The need for an International Anti-Corruption Court (IACC) is greater than ever before

While the ICC is busy with sanctimonious show trials in the Global South, the need for a supranational criminal court that prosecutes corruption without fear and favour is rising.

In the law of the jungle, kleptocracies are shielded by plutocracies. The latter keeps the former in power. A reality all too familiar in a world dominated by the black and white absolutisms of realpolitik. It is for this reason that geopolitical power alliances currently assume complete precedence over the rule of international law. Dictatorial regimes almost always double up as localised kleptocracies. They serve as the ultimate fodder for competing foreign policy interests allowing world powers to act unilaterally outside the purview of international law. Such exchanges are all too typical of fledgling geopolitical arenas in the Global South.

Authoritarianism is applied through totalitarian decree. Both share a top-down and bottom-wide connection to corruption. A kleptocracy derives its economic lifelines from wealthier plutocracies in the Global North in what is otherwise a lopsided system best described as “state welfare economics.”

A world governed by the law of the jungle is a world threaded by corruption

This explains why corruption is a fact of everyday life in developing countries. In such socioeconomic environments, simple clerical tasks cannot be facilitated without bribes or some form of bureaucratic extortion. This mirrors the overall quality of society people in fledging nations live in, while surviving at strictly subsistence levels. A world governed by the law of the jungle is a world threaded by corruption.

Few will disagree with the need for a supranational criminal court dedicated to fighting the scourge of political corruption, but any grand proposition is not without conceptual shortcomings when rectifying practical applications.

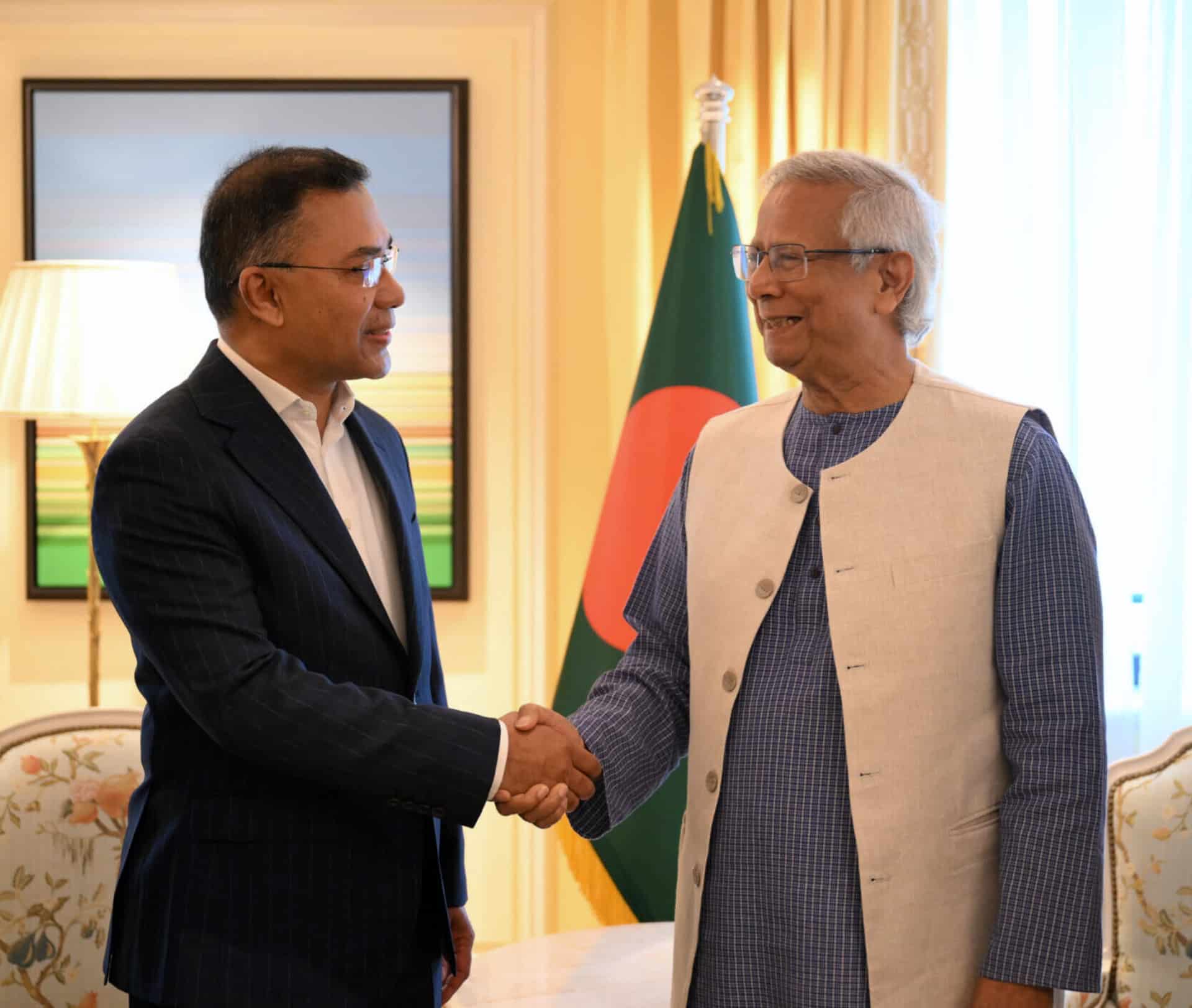

Mark Wolf proposed an IACC at the 2012 St. Petersburg International Legal Forum, an annual conference established on the initiative of the Ministry of Justice of Russia. © Martha Stewart/CC BY-SA 4.0

First proposed in 2012 at the St. Petersburg International Legal Forum by the American federal jurist Mark L. Wolf, the argument for an “anti-international corruption court” was made. This is ironic considering Judge Wolf made the proposition for such a supranational court in what is otherwise the most recognisable kleptocratic plutocracy today: Putin’s Oligarchical Russia.

Therefore, in the case of Russia, one can make the argument that a plutocracy is nothing beyond that of a sophisticated kleptocracy with a permanent seat at the United Nations Security Council. We will even find kleptocrats and their plutocratic counterparts agreeing on the need for an international anti-corruption court.

However, in a world riddled with geopolitical corruption as the de facto standard of international relations among competing world powers, a series of “centenarian questions” must be raised to initiate dialogue on the formation of such a supranational legal entity; but where to begin? Will the court function independently of the International Criminal Court? Would a supranational court dedicated to fighting corruption on the highest levels of government be better served as a direct subsidiary of the ICC?

Read more: What is the difference between the ICJ and the ICC?

Where to begin?

The big picture question prosecuting the effectiveness and impartiality of such a propositional supranational authority comes crashing down to a rather simple conceptual question: how can an International Anti-Corruption Court bring offending state actors and their officials to justice in a world where superpowers impose their own legislation against supranational authorities?

This can, for instance, be seen in the “American Service Member Protection Act” evidenced in Washington’s dealings with the ICC. How will a future International Anti-Corruption Court (IACC) negotiate challenges associated with extraditing offenders from nations that:

- Never recognised the supranational authority of the ICC in the first place or;

- Nations that signed the founding charter of the ICC, but subsequently withdrew due to conflicting interests associated with their respective foreign policies as seen with the United States and the Russian Federation?

Secretary of State for Justice, Dominic Raab holds a meeting with President Judge Piotr Hofmanski. © Tim Hammond/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The United Kingdom and France are the only world powers that have fully committed to the charter of the ICC and stand ready and willing to extradite their own nationals before the seat of international criminal justice, but does such a “matter of fact reality” truly suffice to meet the needs of international criminal justice considering the double standards seen in power alliances shared with greater powers like the United States and China that have since withdrawn or refused to recognize the ICC altogether?

When tasked with the enforcement of international criminal law, the prosecution of political corruption is assumed to be its central modus operandi. Officials standing trial are often implicated in corruption leading to greater crimes against humanity, like war crimes and crimes of aggression, with the latter two prosecuted, but with the former left out.

It is for this reason that the need for a separate supranational legal authority dedicated to fighting political corruption is indisputable, but can only be achieved with an enforcement arm dedicated to the extradition of offenders.

What if INTERPOL was absorbed into IACC?

This calls for a daring proposition: what if INTERPOL was absorbed into the would-be supranational authority of the IACC and housed in a geopolitically neutral nation like Austria or Switzerland? Is such a subordinated alliance possible in a world defined by geopolitical entanglements and diplomatic hypocrisy where immunity is defined by the underlying rulings of realpolitik?

The future success of an IACC will rest in its ability to extradite offenders from the world’s leading powers, rather than just being limited to former washed-up dictators and generals from the Global South where sanctimonious show trials become the standard of international criminal justice.