Five benefits of legalising drugs that may change your perspective

Legalising drugs would make drug use safer, but the bigger impact of moving to a regulated drug market is that it would defy racism, reduce chaos and violence and make us wealthier.

What does decriminalisation of drugs mean VS what does it mean to legalise drugs

When we talk about decriminalising all drugs, within a legal framework, we don’t necessarily refer to them being legalised. In other words, drug ownership and personal use would itself still be legally prohibited, but violations of those prohibitions are deemed to be exclusively administrative violations and are removed completely from the criminal realm. Ideally, we want the legalisation of all drugs, however, decriminalising them could also be an attractive short-term solution. Here are five arguments for legalising drugs.

1. Reducing drug violence and regulating its consumption

Will legalising drugs reduce drug trafficking?

The global market for goods, including drugs, is based on the simple principle of supply and demand. When a government reduces the supply of any particular drug without reducing its demand for it, its price goes up. However, unlike many other goods, the consumption of drugs is not particularly price-sensitive.

As the notorious United States’ ban of alcohol during the 1920s demonstrated, public demand for the drug remained high, which in turn fueled an increase in bootleg booze and speakeasies. But that wasn’t all. It aided the emergence of various mafia gangs and other crime syndicates.

This is often known as the balloon effect, referring to the fact that when squeezing an inflated balloon, it just moves the air around, instead of completely getting rid of it.

Legalising drugs gives us a unique opportunity to address this issue and remove much of the crime and violence associated with it. In 2018, the number of drug-related homicides in Mexico was a whopping 33,341. Imagine saving this amount of lives, just in Mexico!

Moreover, legalising drugs further allows us to regulate its consumption. Currently, most children are easily able to buy various drugs from their friendly neighbourhood dealers, since selling drugs to children isn’t a moral code most drug cartels swear by.

The solution is simple: let us run the drug market, not gangsters!

2. A unique chance to defy racism

Across many nations, drug laws are not only unnecessarily strict, but also fuel systemic racism. This is not breaking news and can easily be observed if one takes the time to look at the relevant data.

In September, Simon Woolley, an ex-No 10 adviser warned Borris Johnson’s government about this very issue: “For decades, politicians from all sides have either turned a blind eye to drug policy failures or weaponised the debate to score cheap political points,” he said. “This has led to half a century of stagnation, which has landed with force on our black communities, driving up needless criminalisation and undermining relationships with the police.”

However, this is not a unique case in the UK. Across the Atlantic, in the United States, black people are several times more likely than white people to be arrested for marijuana possession; even though both groups smoke weed at similar rates. Just in 2020, people of colour made up 94% of marijuana arrests by the NYPD.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZJMeTR227h8

But it is not only the legal system that suffers from systematic racism; the name of a drug like Marijuana, for example, has a clear racist background.

The use of the word Marijuana increased dramatically in the US during William Randolph Hearst’s desperate campaign to create hysteria around the impact of cannabis. In fact, he decided to use a foreign-sounding name (Marijuana) to scare off Americans about an invasion of marijuana-smoking Mexican men assaulting their white women. Scary heh?

True, legalising drugs will not, by itself, solve racism. However, numerous studies have already proven that as the general number of arrests decline, so do the racial disparities that come with them.

3. Stopping systematic drug-related human rights abuses around the world

Capital punishment for drug trafficking is a serious offence across human right’s violating countries such as China, Indonesia, Iran, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore and Vietnam. According to Harm Reduction International, as of 2020, thirty-five countries still retain the death penalty for drug offences.

These thirty-five nations continue to undermine the human rights and well-being of persons who use drugs and that of their families and communities. The practice is not only a blatant breach of drug user’s/traffickers human rights, but also one which is in clear violation of international law.

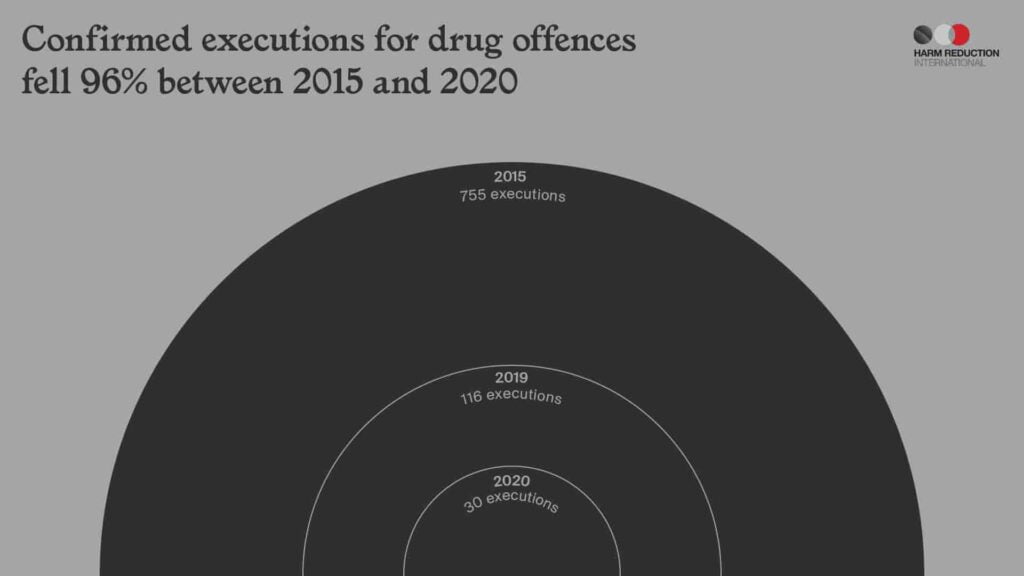

In 2020, Amnesty International recorded at least 30 executions for drug-related offences carried out in only three countries (China, Iran and Saudi Arabia), a decrease of 75% from 2019. Do keep in mind though that the 75% reduction in executions is during a period when most countries are hit by the Covid pandemic and were likely to have strict quarantine and lockdown measures in place. The figure was drastically higher in the anteceding years. In 2019, 122 drug-related executions were confirmed, whereas in 2015 the number of executions was a whopping 755.

Confirmed executions for drug offences fell 96% between 2015 and 2020.

Legalising drugs will have an immense impact on the lives of hundreds who are killed as well as thousands of others across the globe who are on death row for various drug offences.

The United Nations’ 2019 report “What we have learned over the last ten years” is a comprehensive resource on the organisation’s commitments on drug-related matters. One only needs to hope that the UN approaches its solutions with adamant hands.

4. Actually helping addicts

Would legalising drugs increase addiction?

Pretty much everything we have been taught about addiction is a fab. Most don’t get addicted because it is fun, most don’t enjoy being junkies.

During the 1970s, Bruce Alexander, a Canadian psychologist, published a number of studies known as the “rat park experiments”. The experiment essentially studied two groups of rats, both of which were pre-addicted to morphine. The first group was placed in separate cages, while the other group was added to a rat colony, with regular social access to other rats where they could play and have plenty of sex.

Already becoming jealous? No? Just me? Moving on…

During this period, both groups were offered a choice between water and a morphine solution. The shocking result was that the rats living together in the colony drank significantly less morphine than those living alone in isolation.

A similar conclusion resulted from a study conducted on US servicemen returning from the Vietnam war. During various military urine tests in 1971, it became clear that drug use amongst soldiers in Vietnam had reached epidemic proportions. In September 1971, a random sample of 470 soldiers, as well as another sample of 495 soldiers who had previously been tested positive for opioids, were selected and interviewed by sociologist Lee N. Robins.

All the men had been serving in Vietnam for exactly one year, so their exposure to the country’s heroin and opium resources was the same. After a closer inspection, it became known that almost half of all army men enlisted in Vietnam had tried heroin or opium and that 20% of them had developed an addiction to them.

It may seem common knowledge that the availability of a certain drug directly correlates with its consumption. However, what surprised the research team in this particular study was that eight to 12 months after the soldiers had returned home, heroin use was uncommon, even amongst those who had previously become addicted to the drug in Vietnam. In fact, during the first year back home, only 5% of men had relapsed to addiction.

Although both experiments have their limitations when it comes to the repeatability and applications to society, they both teach us a valuable lesson: environmental factors matter and must be an undeniable aspect in prevention programmes and policies impacting drugs and crime.

Our penal system must be rehabilitative, not vindictive. Let’s not forget that a criminal conviction relating to drugs can have devastating effects upon someone’s life. It can cause personal relationships to fall apart and limit future work opportunities and further alienate those who are in desperate need of our help. This doesn’t need to be the case. Instead of stopping drug users, let’s support them instead.

5. More tax money

Legal drugs present the possibility of tremendous benefits to economies especially as a means to recover from the pandemic induced economic downturn.

Looking at this again, over the past few years, the sale of a drug like marijuana in states like Colorado and Washington have resulted in buoyant tax revenues. According to a report from Arcview Market Research and BDS Analytics, cannabis sales in the country were $12.2 billion in 2019 and projected to increase to $31.1 billion by 2024.

But that’s not all, we will also be able to save vast sums of money as fewer law enforcement officers would be required and fewer court cases involving drug substances would go to trial. Legalising drugs can also create more jobs and investment opportunities.

Reform! The drug legalisation debate can be a complex one, however what is clear is that the war on drugs was an ill-advised policy that we have been pursuing for the last 80 years.

It is time we listen to experts. It is time that we understand that nations don’t live in a vacuum and global challenges require global solutions.

Drugs can bring us joy; drugs can harm us. Legalise them and give them to doctors, pharmacists and regulated retailers, not criminals.

Please contact us if you have any comments or would like us to write about potential arguments against legalising drugs.