Bangladeshis have traded a secular autocrat for a dynastic exile. On February 12th, the first competitive polls in 18 years delivered a two-thirds majority to the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and its leader, Tarique Rahman.

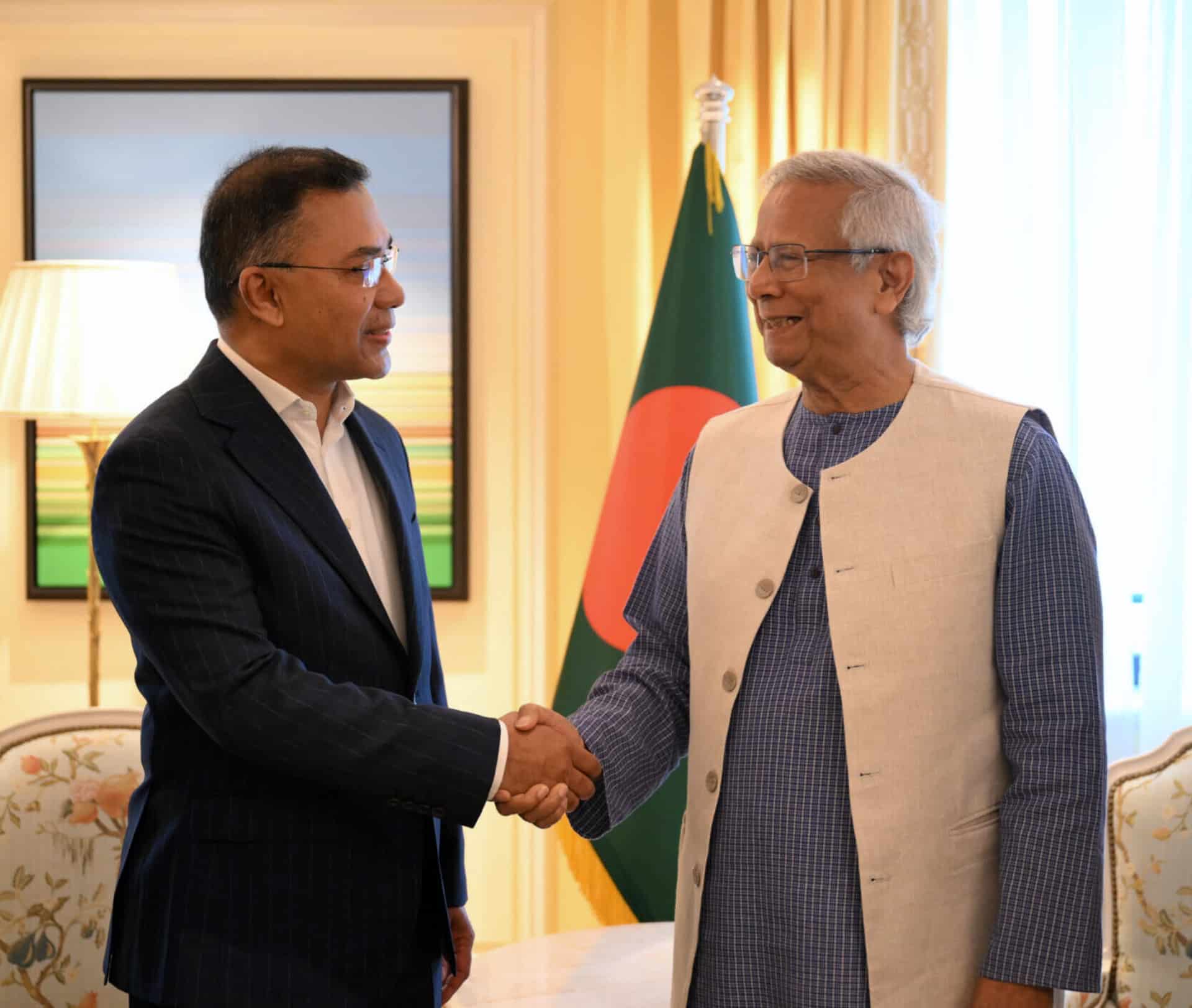

Mr Rahman, who recently concluded 17 years of London exile, now inherits a state still reeling from the August revolution that toppled the 15-year regime of Sheikh Hasina Wajed. While 1,400 lives were lost during the uprising, the subsequent transition has proved orderly.

Close to 70% of voters endorsed a constitutional referendum intended to shackle future premiers with term limits and a new upper house. Whether a party that once presided over five consecutive years at the nadir of global corruption rankings will respect these new constraints remains a matter of profound scepticism.

The political landscape has shifted beneath the feet of the student revolutionaries who sparked the move for change. The National Citizen Party, representing the Gen-Z activists, secured a paltry six seats after a flawed alliance with Islamist forces.

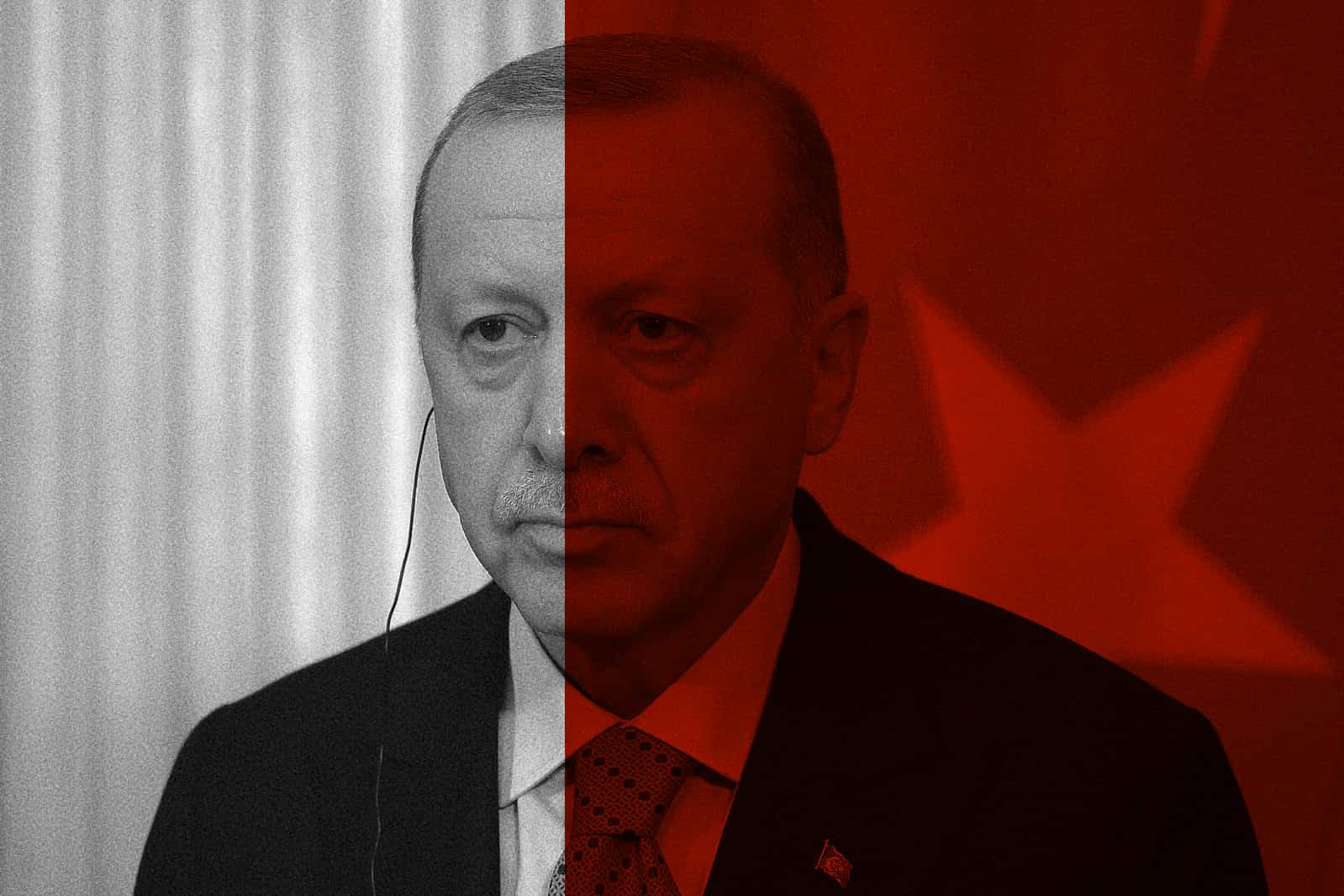

In their stead, a coalition led by Jamaat-e-Islami has surged to 80 seats to become the primary opposition. This represents a seismic shift for a group that previously struggled to exceed 18 seats and still refuses to field female candidates.

With the Awami League banned and Ms Hasina sheltering in a Delhi bungalow, a 60% turnout suggests a significant portion of the electorate stayed home. Bangladesh has successfully rewound the clock to the competitive politics of the 2000s, yet it has added a potent dose of religious populism to an already volatile mix.