The Ultimate Guide to Caravaggio's Nativity with Saints Lorenzo and Francesco

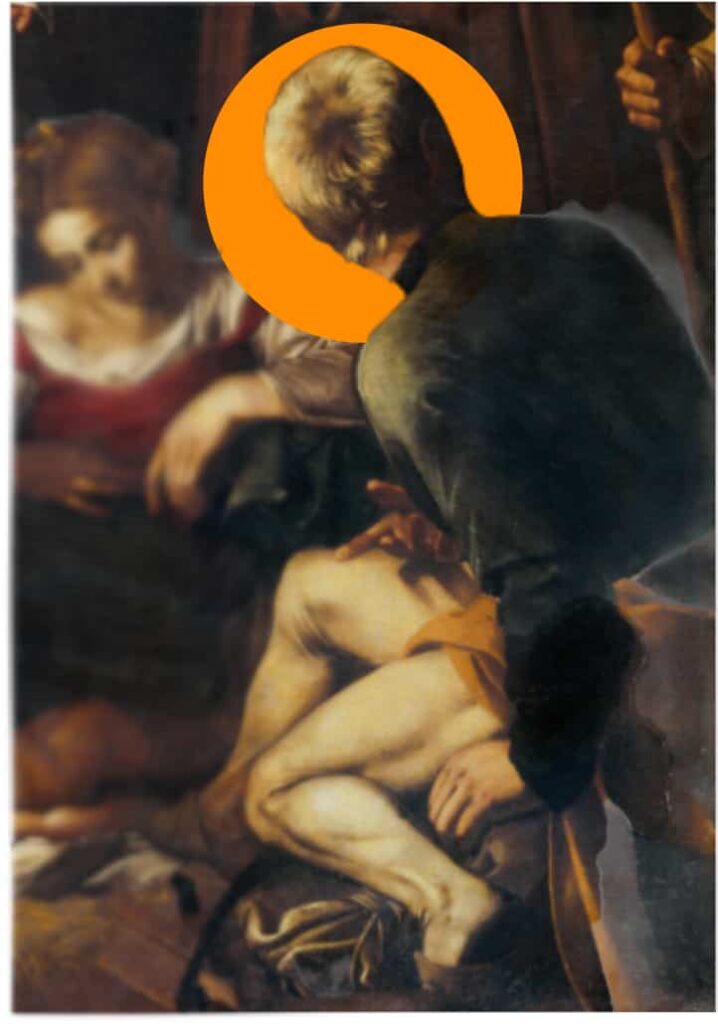

Painted during the 1600s and stolen in 1969, Caravaggio’s Nativity With Saints Lorenzo and Francesco is a master work that celebrates the sacredness of the moment without idealising its origins.

The Lost Nativity

The multiplicity of subjects and themes present in Caravaggio’s works allows me to continue talking about him, through his works, even in the period of the year when each of us could succumb to the easy temptation to choose discounted topics, through clichés. During the month of December we were constantly bombarded with images that create romantic and idealised suggestions. Despite the decidedly muffled atmosphere, I will try to talk with you about the nativity in art trying to maintain a critical, attentive and open attitude.

For a very long period of time almost all works of art were mainly focused on sacred subjects and themes. For this reason there are countless nativities that I could offer you, but as always I have preferred to share with you a profound emotion rather than in depth knowledge. Relying exclusively on my feelings and my personal taste, I chose to talk about a work by Merisi: the Nativity with Saints Lorenzo and Francesco, created by Caravaggio more or less in 1600.

Caravaggio’s Nativity with Saints Lorenzo and Francesco is one of the gorgeous examples of Nativity in art. The photo has been slightly brightened.

An emotional analysis: Nativity with Saints Lorenzo and Francesco

This canvas offers a vision of the nativity that manages to celebrate the sacredness of the moment without idealising its origins, and it does so through a construction of images and atmosphere, which I feel is close to my very personal idea and image of the nativity.

Merisi’s gaze has always been an attentive gaze to truth, to the essence, focused on the moment, devoid of arid decorative trappings. Like modern directors, Caravaggio’s narrative ability finds perfect spaces and faces for the story he wants to tell, narrating it through looks, expressions, poses, but above all through the perfect alternation between light and shadow.

These characteristics that I would define constant in his works, we also find in his nativity, an oil on canvas, therefore during the Roman period of the artist, for an oratory in the city of Palermo. This canvas, in addition to what I would define stylistic coherence, is the most “Caravaggesque” of all the master’s works because in a certain sense it traces his history.

In fact, the painting has suffered somewhat the same fate, in beauty and “inaction”, as its author. Just as Merisi disappeared from the Roman scene after committing a murder, so the canvas of the nativity in 1969 disappeared from the oratory that housed it following a commissioned theft.

But who commissioned the theft of the painting?

In reality this mystery is still ongoing. There are those who speak of theft carried out following an order from the mafia, who simply refer to the black market of works of art.

As in any self-respecting mystery, there are many hypotheses, but none have proved reliable, so much so that even today the Nativity of Caravaggio is among the most sought-after works in the world. Precisely for this particular situation, it will therefore be possible to talk about the canvas by referring only to the photographic material prior to the date of the theft.

The most evident aspect for me from the examination of the canvas is that each character present in the nativity seems to experience the event he is witnessing according to a completely personal yardstick. Every sensitivity, every personal awareness, is transmitted to us through a silent dialogue made up of looks, expressions and movements.

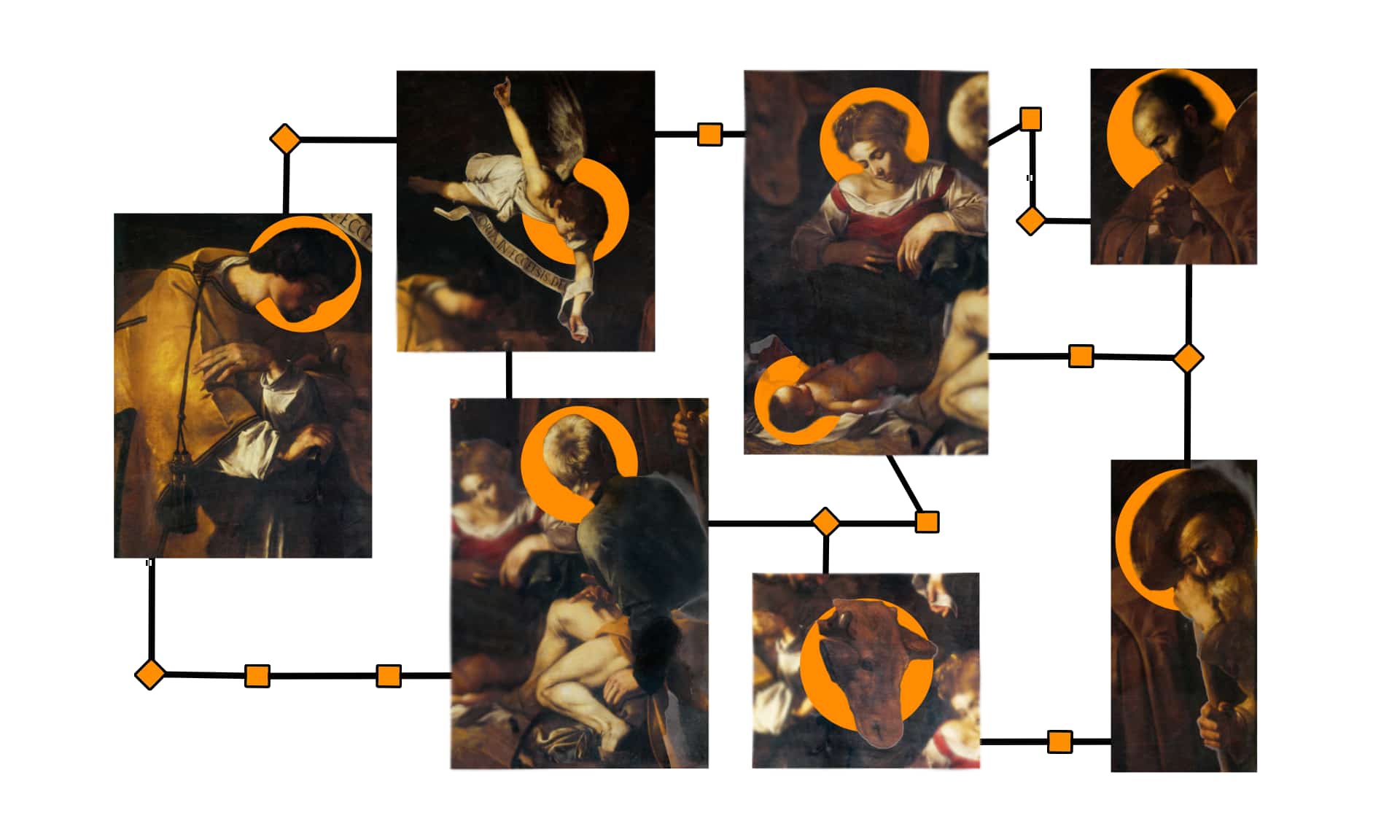

The Angel & his message

Looking at the canvas starting from the left at the top, we find an angel proclaiming glory through verses written on a cloth that the angel himself holds in his hands. The cherub is depicted in a particular pose, the position of his arms is not only linked to the functional need to create balance within the canvas; his right arm appears stretched upwards, his left downwards. This different inclination in addition to the scenic balance already mentioned, transmits to us the very purpose of the presence and message of the angel which is a symbol of God’s closeness to men.

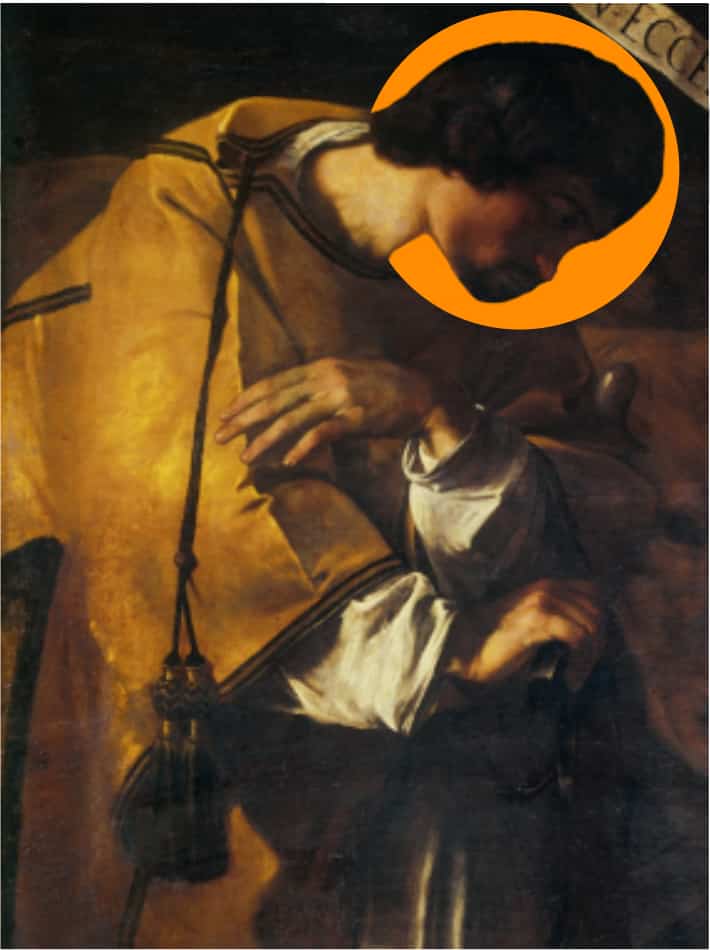

San Lorenzo

Still on the left but below, we find San Lorenzo, depicted inside the nativity because he is the owner of the Palermo chapel. The saint appears dressed in a golden religious robe, his gaze is turned towards the child Jesus. Lorenzo appears absorbed in his thoughts, in a meditation that is something more than simple prayer, almost an awareness made perceptible above all thanks to the play of light, as always, expertly orchestrated by Caravaggio.

While the mantle of the saint, directly illuminated, seems to light up until it becomes gold, the half-light envelops the face of the saint, an evident sign of the awareness of his future martyrdom (by fire); a foreshadowing that also transpires in the pose of Lorenzo who leans, almost to draw strength and support, towards the grill that will be the instrument of his death. The saint’s gaze is turned to the child Jesus, he observes him with tenderness and once again I underline with the same strong awareness, of which I spoke before, of their common destiny.

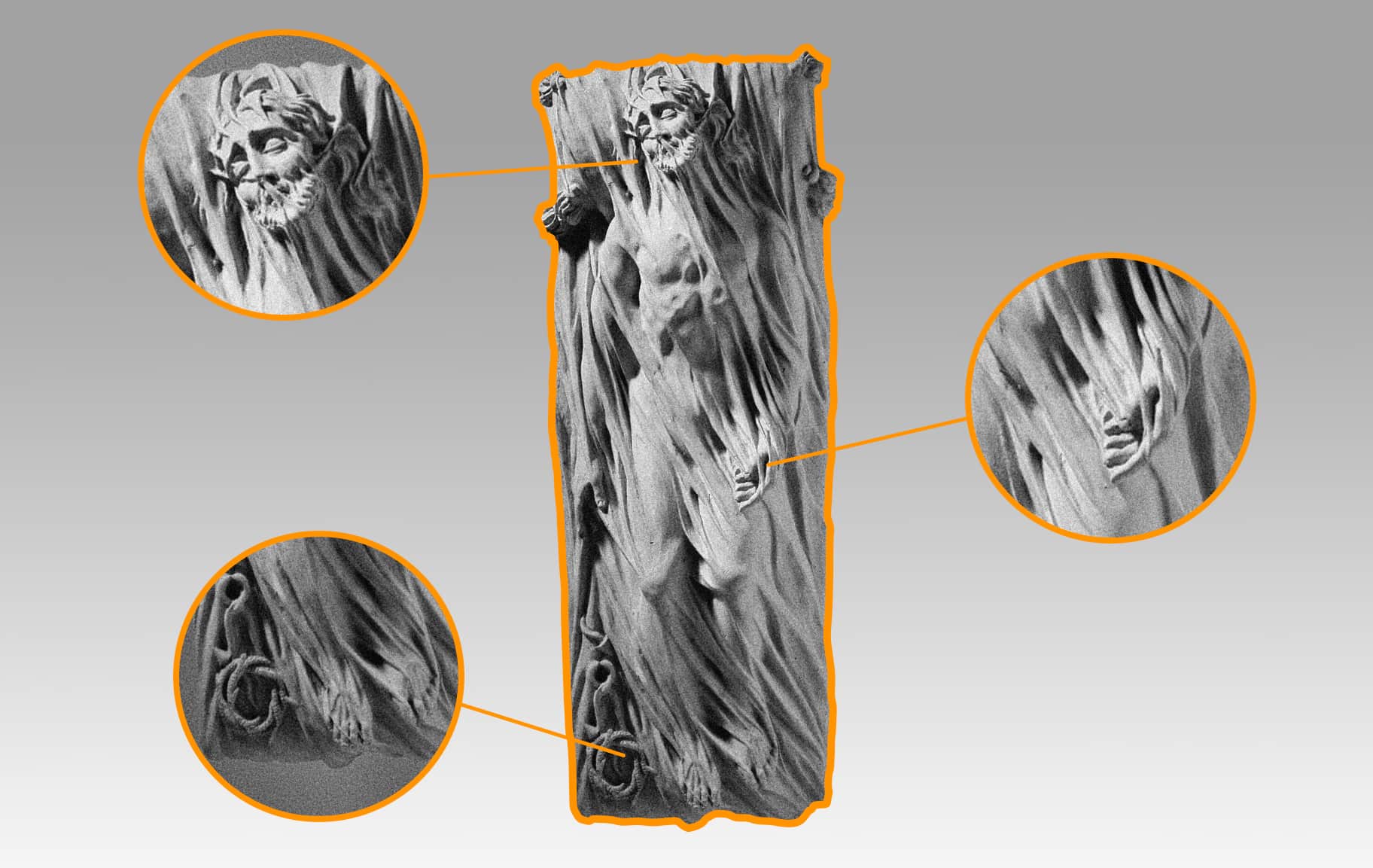

The ox and the donkey

Proceeding in the reading of the images next to Lorenzo we find the ox hiding the body of the donkey. The figure of the two animals, traditionally accepted within the nativity, is in most cases depicted behind the main characters. In our case, on the other hand, the ox is placed right next to San Lorenzo, as if to testify to the university of the message of the divine birth.

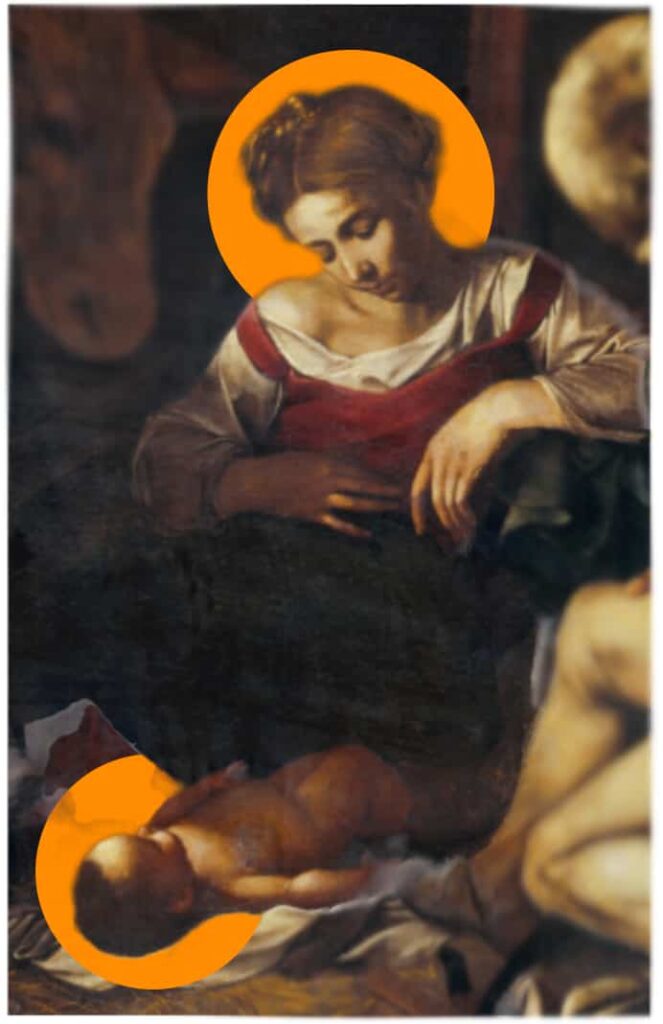

Mary and baby Jesus

At the centre of the scene, almost as if to divide the characters on the right from those on the left, we find Mary and the baby Jesus. The latter, lying on a sheet placed on straw, seems to observe the angel but above all seems to seek the gaze of his mother.

Although Mary is obviously present in the scene, she seems to be elsewhere. By carefully observing her image, in fact, you can notice that although the Virgin has her gaze turned downwards, she is not looking at the child, but at an unspecified point. Like Lorenzo, she seems to be meditating more than observing. She too is not living the present but the future, projected towards the destiny of her son.

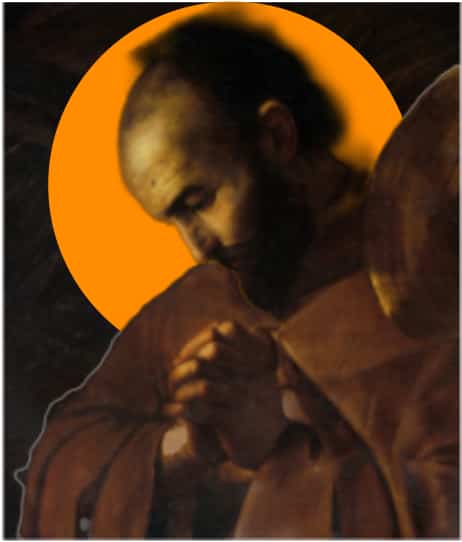

St. Francis

Behind Mary, absorbed in prayer, we find the image of St. Francis, according to tradition the first to have staged the nativity. Both St. Lawrence and St. Francis are inserted in the pictorial context of the canvas to satisfy the cult reserved for them by the faithful of the oratory. Observing the whole scene with a more “technical” than an interpretative gaze, we find a clear and precise line that can be traced by joining the three points represented by the heads of Jesus, Mary and Francis.

This line of inclination with the flight of the angel, contributes to the perfect balance of the represented scene. Every single character examined so far, shares a role in my introspective opinion, linked to a personal meditation that does not belong to the last two characters depicted on the right.

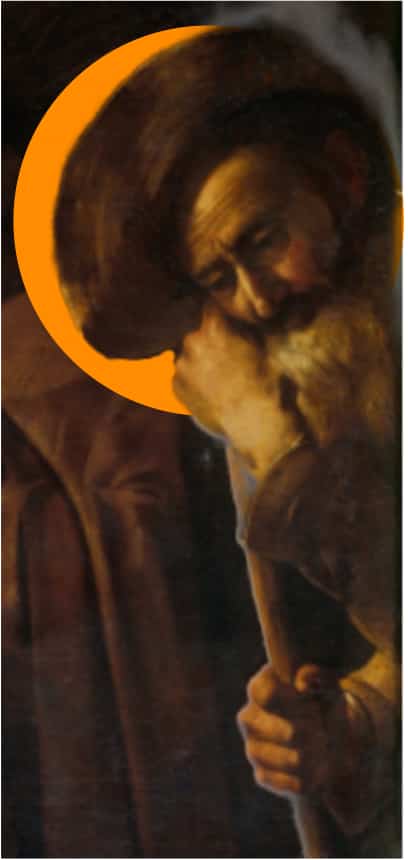

Is the mysterious man Fra Leone d’Assisi?

According to some, the elderly and bearded man represented in the upper right could be Fra Leone d’Assisi. I personally believe that this hypothesis is implausible, dictated more by the closeness to Francis than by the objective examination of the iconographic elements.

The man, although not completely visible, has a very different clothing from that of Francesco both with regards to style and fabric.

I believe that the hat and the stick with which he is provided identify him with one of the shepherds, who according to the scriptures, presented themselves in front of the Child after having listened to the good news of the angels.

Saint Joseph

Among the various characters on the canvas, the one who most of all breaks the mould, is Saint Joseph, who in the work appears depicted at the bottom right, portrayed from behind, in the act of speaking to the shepherd behind him. Although Joseph’s face is not visible, his figure appears to be equally communicative and revolutionary.

The saint, despite being depicted with white hair, does not convey the same idea of old age present in almost all the works that portray him. In fact, Joseph’s body speaks to us of something else, his muscular legs, his broad shoulders are those of a strong, young man. The dynamic pose, reserved exclusively for him, conveys the idea of a muscular tension almost completely absent in the other subjects depicted.

This very different and new vision of Giuseppe is even more emphasised by the bright green colour of his robe, a colour that is rarely reserved for this character. The dialogue between Joseph and the shepherd is then completely compatible, in my opinion, with the artistic vision of Caravaggio. A vision that has always led him to choose the faces of his characters from among the humblest, offering them that dignity that society, the real world, too often denied them.