From Michelangelo to Michelangelo: The story behind Caravaggio his "Death of the Virgin"

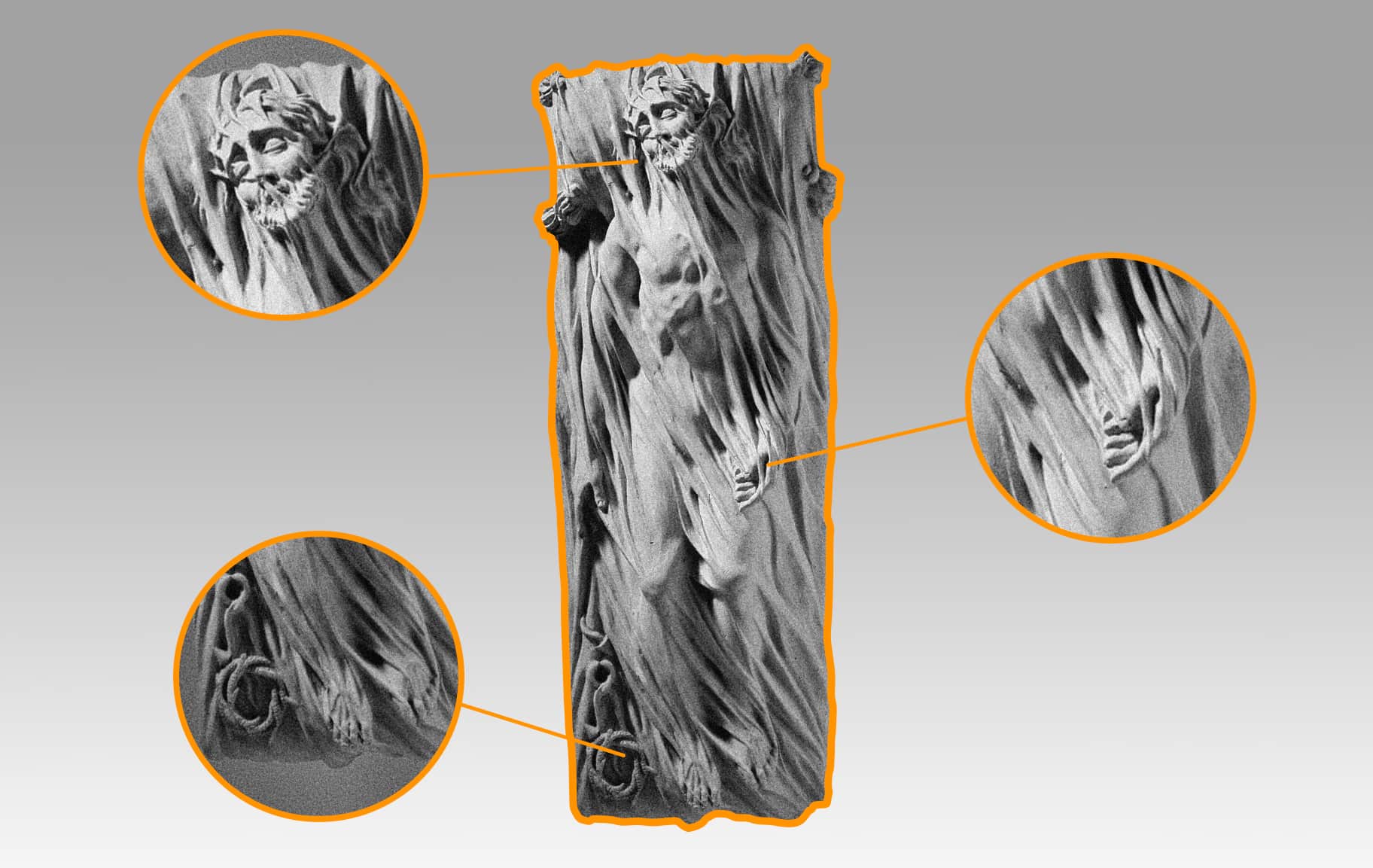

I don’t think I have yet reached my own style in writing and I don’t even think I want to reach it so as not to end up entangled in webs created by myself. I do not love to rely on chance, but do enjoy spontaneous and sudden thoughts. Precisely for this reason, following what came to my mind as soon as I delivered the last article, I decided to continue talking about freedom of expression in art, just as I had already done when talking about Michelangelo’s Pietà Rondanini.

I will continue to examine this theme by talking about another artist with the same name as the previous one: Michelangelo Merisi better known as Caravaggio (Milan: 1571 ~ although for many years it was believed that he was born in Caravaggio, Porto Ercole: 1610).

Not that Michelangelo!

Caravaggio was a man who I believe had an innate sense of freedom of expression. In fact, right from the start, he possessed a very clear and personal conception of art, which led him, regardless of personal stylistic or conceptual evolution, to overcome the artistic clichés of his period. This Michelangelo was a rebellious man, a victim of his own character, or perhaps as some recent studies also suggest, a victim of a difficult character combined with the reaction of his body to prolonged contact with the substances used to obtain his sensational colours.

Background and beheading sentence

Caravaggio’s first artistic training took place in Milan where he only rarely manifested the rougher aspects of his character, subsequently the places where he found himself living and creating works were mainly Rome, Naples, Malta and Sicily. In the very early Roman period Caravaggio achieved some success, because at the time he limited himself to painting portraits and reproductions of sacred subjects.

Over time he began to introduce revolutionary elements and colours that indeed led him to fame, but also to the inevitable scrutiny that has always accompanied innovation.

Some of his commissioned works were even rejected by clients, not only because they did not know how to interpret the artistic innovations, but also because of the controversial choice of his models. The refused works, however, were only a small part of Caravaggio’s problems, especially in Rome. In fact, it was in this city that the first violent episodes related to the painter’s excesses of anger occurred. These resulted in the very serious episode culminating in the murder of his rival, Ranuccio Tommasoni, which took place during a ball game (Jeu de paume).

The crime was said to have been provoked by the victim who was Caravaggio’s rival in love. Caravaggio was sentenced to death by beheading, which legally could have been carried out by anyone who met him on the street. The painter managed to survive only thanks to the protection of the Colonna family, especially Philip I, who after hosting him in several of his properties, managed to help him escape to Naples, Malta, and Sicily.

Once in Naples, thanks to the protection of the Colonna, he was able to create several paintings, certainly some of his best known works. Beheading scenes or severed heads, are a recurring theme, which testify to Caravaggio’s inner torment relating to his sentence.

After Caravaggio managed to reach Malta with Colonna’s help, he painted a number of works including his famous ‘Beheading of St. John the Baptist’. Here Caravaggio, thanks to his artistic merits and a series of acquaintances, managed to become a Knight of Grace, but following a quarrel with his superior he had to move again. He travelled to Sicily, where he continued to produce paintings and began to take an interest in archeology; his restless spirit led him to move back to Naples where among his various works he painted his last painting: the “Martyrdom of Saint Ursula”.

Martyrdom of Saint Ursula

When the news of a possible revocation of the death sentence arrived, Caravaggio decided to head for Rome. Even though the papal pardon was confirmed, the painter never completed his journey because he died in Porto Ercole probably due to a long-neglected intestinal infection.

I considered it useful, if not fundamental, to touch upon the history of Merisi in order to understand the inner torment of this outstanding artist who during his life sowed death (he was actually involved in two murders), while at the same time touching eternity at its best and giving us, as I said at the beginning, his particular perception of art. His having to constantly move from one place to another, always running away from something or someone, is not only the consequence of violence, but a reflection of the fury of the indomitable spirit of the painter.

The Death of the Virgin

Deciding which painting to talk about in this article was difficult because the entire Caravaggesque production leaves me speechless. My instinct, however, helped me in this endeavour and led me to choose a painting that falls within the list of works that were refused by his clients, namely, ‘The Death of the Virgin’.

The Death of the Virgin currently exhibited in the Louvre Museum

The painting, currently exhibited at the Louvre Museum in Paris, was completed between 1604 and 1606, under commission of the jurist Laerzio Cherubini who wanted to exhibit the canvas in his private chapel in Santa Maria della Scala in Rome. Not only did Caravaggio not respect the deadlines of the contract, but he presented a work that had nothing in common with the aesthetic and iconographic canons of the other artistic works of the time.

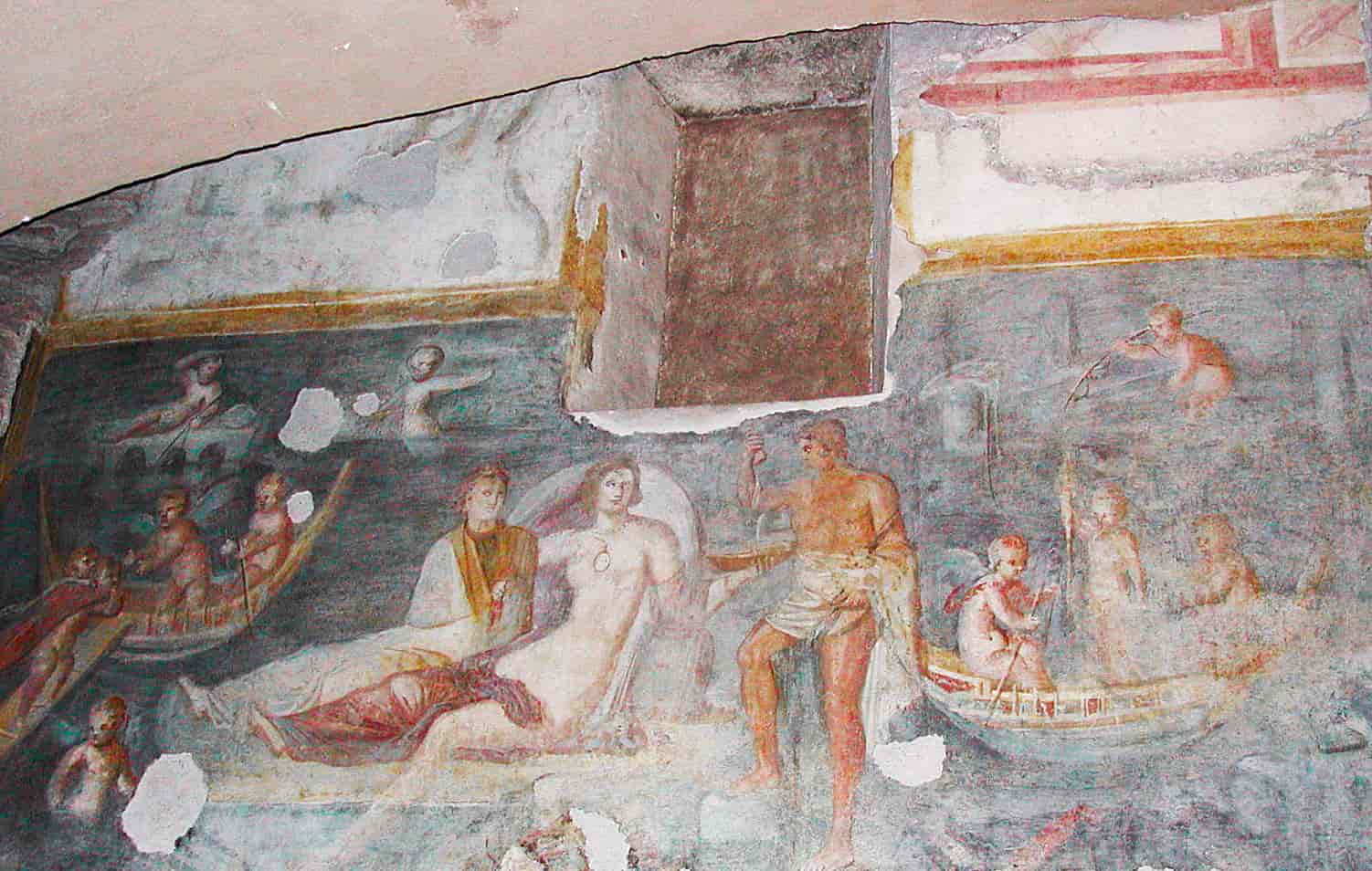

The painting reproduces a rather humble and sparse environment, enriched only by a cardinal red cloth that is conceptually linked to the scarlet red of the Virgin’s robe.

Here the shadows, so loved by the artist, are concentrated mainly on the left and in the rear area of the canvas. Flashes of intense light frame only some of the faces of the apostles, the Virgin and Mary Magdalene, whose face is not visible because the head is folded over her legs as if to hide the tears.

The serene resignation in the face of death, typical of the sacred characters of the past, disappears completely in this atmosphere of pathos, of participation and of apostolic dismay. The biggest scandal, however, was not this interpretation of pain, which by the way already had precedents in art, but the choice of the model and the pose reserved for the Virgin.

In fact, Mary has nothing of the transcendence reserved for her. She is depicted as an ordinary person in the face of death, she sees a lifeless body, in a pose that escapes the control of the mind, abandoned by physical strength and control. The bare legs, the tousled hair, but especially the swollen belly, were undoubtedly a set of excessive elements for the taste and expectations of the times that required a forced respectability detached from human reality, rather than a plausible representation.

This death scene is not doctored; it is deeply anchored in reality.

The scene is not that of people of noble or high lineage, but of the people belonging to the same reality from which the Apostles and the Virgin came. When in Rome, Caravaggio often had the opportunity to closely observe corpses, even after several days of death. It is therefore thought that the swelling of the Virgin may be the result of this observation. Tradition has it that in the picture the corpse of a prostitute, drowned in the Tiber, was reproduced; others propose the reproduction of a pregnant prostitute. Whatever the truth may be, we cannot know.

Frankly I do not even think it is important to know. Caravaggio was not understood because he did not want to filter reality. He was not able to lie, especially in the face of death; even when it really represents a rebirth as in the case of Mary, which we must not forget was, according to the Christian tradition, taken up into heaven. The religious tribute that other artists have wanted to exult through the ephemeral idealisation of beauty, here is to be found and recognised in the profound pain of the apostles and of Mary Magdalene. It is witnessed and exalted through strong colors and the true beauty of simple things.