The Rise of the Angry Young Men in British Drama

Exploring social injustice and generation gap in post-war Britain drama through the works of John Osborne and other playwrights of the Angry Young Men movement.

‘A Look Back in Anger’ by John Osborne

Drama, like the novel, reflected the discontent and disillusionment of the younger generations. The Angry Young Men were not only novelists but also playwrights.

Look Back in Anger by John Osborne was certainly the turning point of British drama. The main character, Jimmy Porter, an intellectual who had to work in the market-place to support his family, represented that new kind of dissatisfaction and rage. He, in fact, was rejected by society and subsequently turned against it with indiscriminate fury.

Like Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim, Jimmy Porter was dissatisfied with his situation and reacted against it. Social injustice is one of the major themes in the work of John Osborne.

The term Angry Young Men was coined in the wake of his Look Back in Anger.

Osborne attacked the complacency of the English and the main character Jimmy Porter expressed the human suffering and the social struggle. The angry young men were those who belonged to the lower classes, but who were given the chance to exploit a complete formal education; neo-intellectuals who reacted to the old conservative standards of class distinction with strength and disdain.

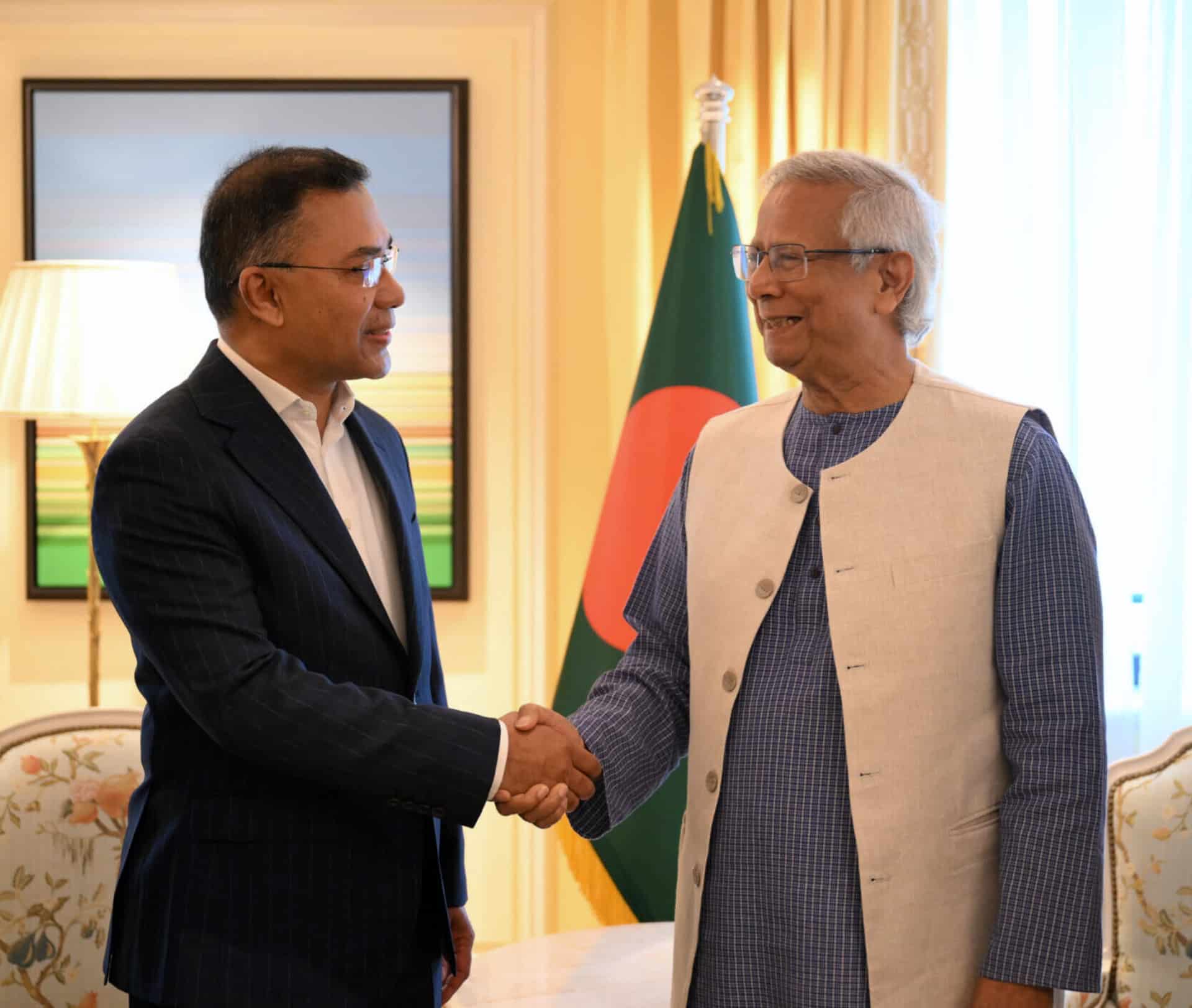

Richard Burton and Mary Ure in Look Back in Anger (1959). Photo: Screenshot from the movie.

Another characteristic of Osborne’s work is the study of the generation gap, which highlighted the fracture between the stable values and national greatness of the past, and the social protest and declining importance of Post-War Britain.

Learn more: John Osborne: his life and works

The structure of his plays reversed the traditional settings and conventional parameters of post-war English drama by doing away with classical theatrical methods.

The structure followed the basic three-act play created by the French dramatists Eugene Scribe (1791-1861) and Victorien Sardou (1831-1908).

John Osborne

Osbome did away with flashbacks and created a circular development in the progression of his story. In Look Back in Anger, for example, the setting in the first act is identical to the third act, a fact which underlines the repetitive nature of daily routine.

Apart from the social sense of frustration in Osborne’s plays, which marked a break from the traditional themes of the plays belonging to pre-war Britain, the innovative language was also uniquely distinctive.

The language, up to that point in time, had been created for the upper-class theatregoers, polished and somewhat ostentatious, Osborne’s characters, by contrast, used slang, colloquialisms and the everyday simple language; the language of the middle and lower classes.

It must be remembered that Osborne had worked in the theatre when he was a young man as an actor and it was that experience which helped create in him the acute sense of stage and theatre. His work always reflected those essential theatrical elements which revealed man’s relationship with society and with himself.

Other Angry Young Men playwrights

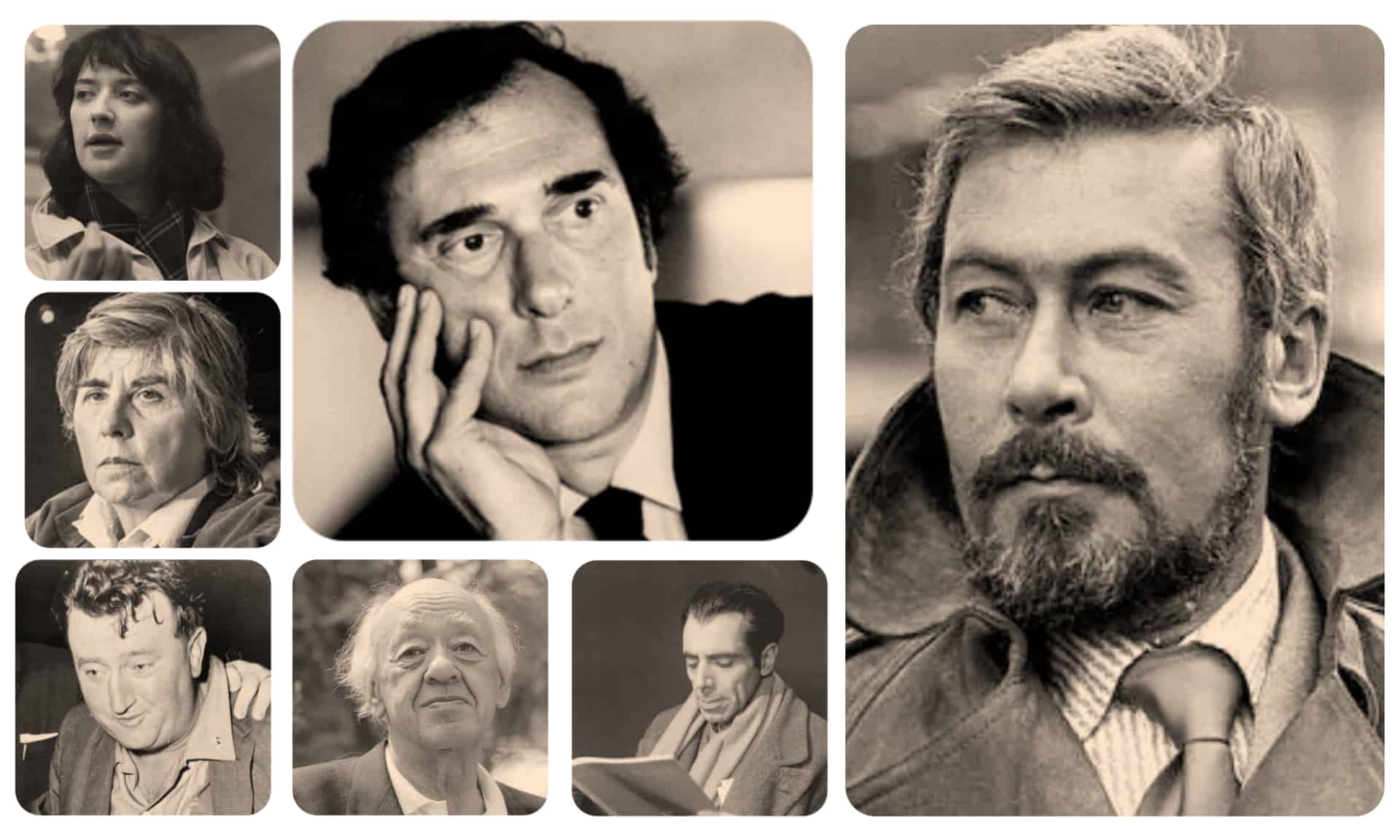

Other dramatists who expressed anger and sarcasm at the post-war society were Arnold Wesker and John Arden.

Wesker dealt with the discontent of the working classes. His work was politically motivated and it highlighted the problems of Osborne’s Jimmy Porter, as being those of society and not merely of an individual. Arden’s Musgrave’s Dance (1959) was his best work. It dealt with war and peace and was influenced by Brecht. Other writers worthy of mention are Brendan Behan, Shelagh Delaney, Ann Jellicoe and Bernard Kops.

Protesting against society and the situation of man, but in a different way, were the giants of the Theatre of the Absurd Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter.

Learn more: Samuel Beckett & Harold Pinter: 2 Giants of the Theatre of the Absurd

Both playwrights developed a new drama which was characterised by features that had nothing in common with the prevailing criteria of the time.

‘Waiting for Godot’ by Samuel Beckett

Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (1952) shocked the traditional critics who desperately searched for plot, characterisation, orchestrated dialogue or just a plain simple story… and found none.

This new drama, known as the Theatre of the Absurd, was in fact the incarnation of the imperceptible situation man found himself in during the post-war society. So imperceptible and so undefinable, that the characters of Beckett’s play are surrealistic, as is their incoherent dialogue and the setting itself. Time loses all sense and meaning.

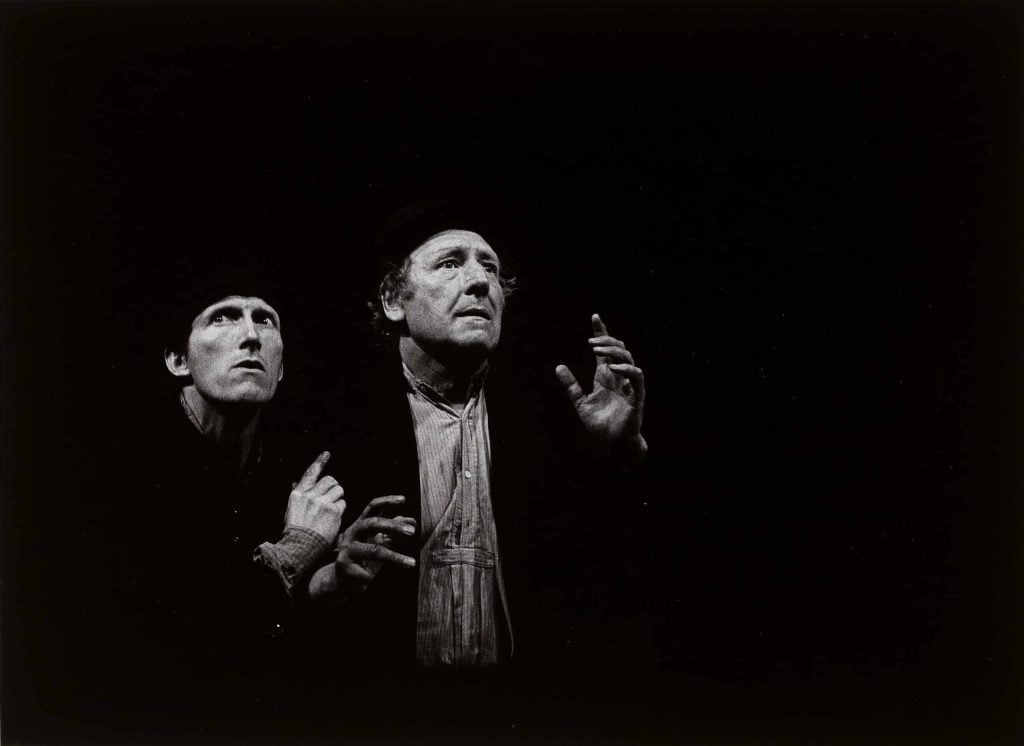

A 1978 staging of Waiting for Godot by Otomar Krejca. Rufus (Estragon) and Georges Wilson (Vladimir). Photo: Fernand Michaud.

In a period of two days, a dreamlike situation unfolds as a dead, withered tree regains its full bloom. Two characters, Pozzo and Lucky, who are normal on the first day, are both handicapped on the second, Pozzo is blind and Lucky is dumb. What is more surprising is that we learn that they have been blind and dumb for a long time.

This surrealistic quality of the play is also evident in the static development of the two main characters, Vladimir and Estragon. They talk to each other, but they do not communicate. They take decisions which they never follow. They wait endlessly for Godot, who never appears. The whole work is more like dramatised poetry, or music.

Herbert Blau, who directed the play for 1400 convicts at San Quentin penitentiary in 1957, compared the play to a piece of jazz music in which one could search for any interpretation of feeling or understanding.

Referring to jazz, which is characterised by improvisation and not altogether harmonious rhythm, helps us understand the definition of absurd, which, in musical terminology actually means ‘out of harmony’.

Albert Camus had already described this separation between man and his environment in his essay, The Myth of Sisyphus (1942). This is how he diagnosed the disharmony in our alien world:

“A world that can be explained by reasoning, however faulty, is a familiar world. But in a universe that is suddenly deprived of illusions and of light, man feels a Stranger. He is in an irremediable exile, because he is deprived of memories of a lost homeland as much as he lacks the hope of a promised land to come. This divorce between man and his life, the actor and his setting, truly constitutes the feeling of Absurdity.”

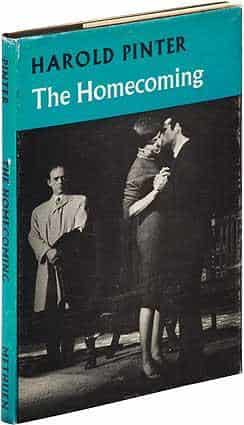

‘The Homecoming’ by Harold Pinter

Harold Pinter’s plays also belong to the Theatre of the Absurd in that they express visually what is felt poetically. His characters, like Beckett’s Vladimir and Estragon, speak in nonsequiturs and are unable to explain their actions.

Learn more: Harold Pinter: a mirror for the common people

Pinter’s characters are even more inconsequential when they converse. They just talk for the sake of talking. This Pinteresque style of dialogue, as it has come to be known, is really typical of the disharmony Pinter wanted to portray.

He saw man as an object that simply existed. He echoed Beckett’s description of man as “a scrap of life surrounded by death, a something encircled by nothing”.

In Pinter’s The Homecoming one of the characters attacks his family with words which could very well have been expressed by Pinter himself in relation to man.

“You wouldn’t understand my works. You wouldn’t have the faintest idea of what they were about […] It’s nothing to do with the question of intelligence. It’s a way of being able to look at the world. It’s a question of how far you can operate on things and not in things [.] You’re just objects. You just [.] move about. I can observe it. I can see what you do. It’s the same as I do. But you’re lost in it.”

Other dramatists of this new drama include the Russian, Arthur Adamov (1908-1970), and the Frenchman of Romanian origin, Eugene Ionesco (1909-1994) who became one of the leading dramatists of the French avant-garde.

British Drama in the 60s and 70s

The theatre that developed during the 1960s and 1970s shifted from experimental to traditional.

Two playwrights worthy of mention are Tom Stoppard (b.1937) and Robert Bolt (1924- 1995). The former wrote Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1966) and Travesties (1974), while the latter kept to the traditional theatre with his Chekov-like Flowering Cherry (1957), A Man for all Seasons (1960) which was made into a successful cinema version, and Vivat Regina (1970), a historical drama on Queen Elizabeth I and Mary Stuart.

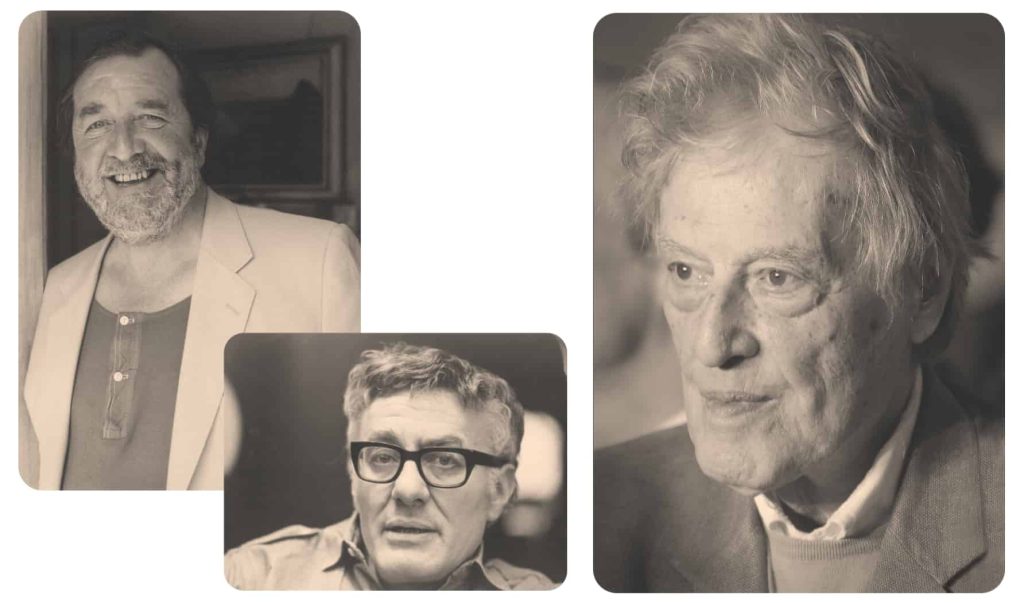

Right to left: Tom Stoppard, Peter Shaffer and Robert Bolt

Another traditionalist was Peter Shaffer (1926-2016) who wrote The Royal Hunt of the Sun (1964), a play on the conquest of Peru; Equs (1973); and Amadeus (1981) which focused on the dying Mozart’s accusations of the rival Antonio Salieri for poisoning him.

During the 1930s many critics and intellectuals had predicted doom for the theatre, foreseeing the complete take-over by the new and more enticing cinema. Even George Bernard Shaw, in the New York Herald Tribune (August 7, 1930) stated:

“The poor old theatre is done for […] there will be nothing but ’talkies’ soon!”. Jane Cowl, an American theatre actress, addressing members of the Women’s Graduate Club of Columbia University in 1929 asserted that “We are being mechanised out of the theatre by ‘talkies’ and radio, and by people who prefer convenience to beauty.”

Luckily the vigour and vitality of the theatre after the 1940s proved them all wrong.