The fresco that saved a city: Piero Della Francesca's Resurrection and its enduring power

Aldous Huxley’s praise for Piero della Francesca’s Resurrection once moved a British officer to spare a town—showing how art can outlast war and shape destiny.

Piero della Francesca’s Resurrection belongs to the numerous works that were decisive in the birth of new ways of interpreting art, both stylistically and conceptually, yet are unjustly known only to a relatively limited public of experts or true enthusiasts.

Indeed, the artist himself, though he influenced the style of more famous painters such as Raphael, is more often recognised as a name rather than through immediate association with one of his many works.

And yet, the fresco of the Resurrection recounts the depicted event in an entirely new way, with a resonance that, as we will see, has truly crossed the centuries.

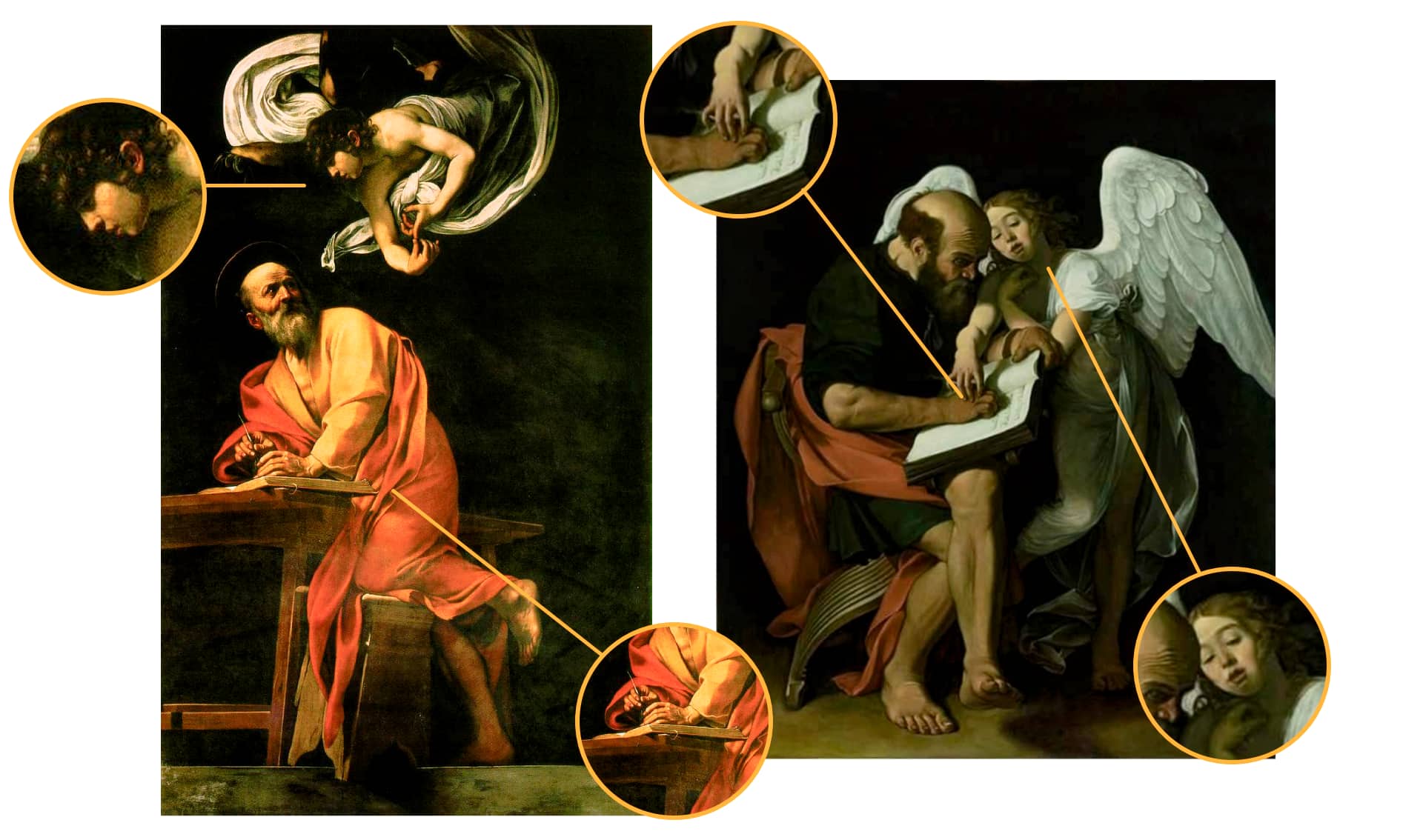

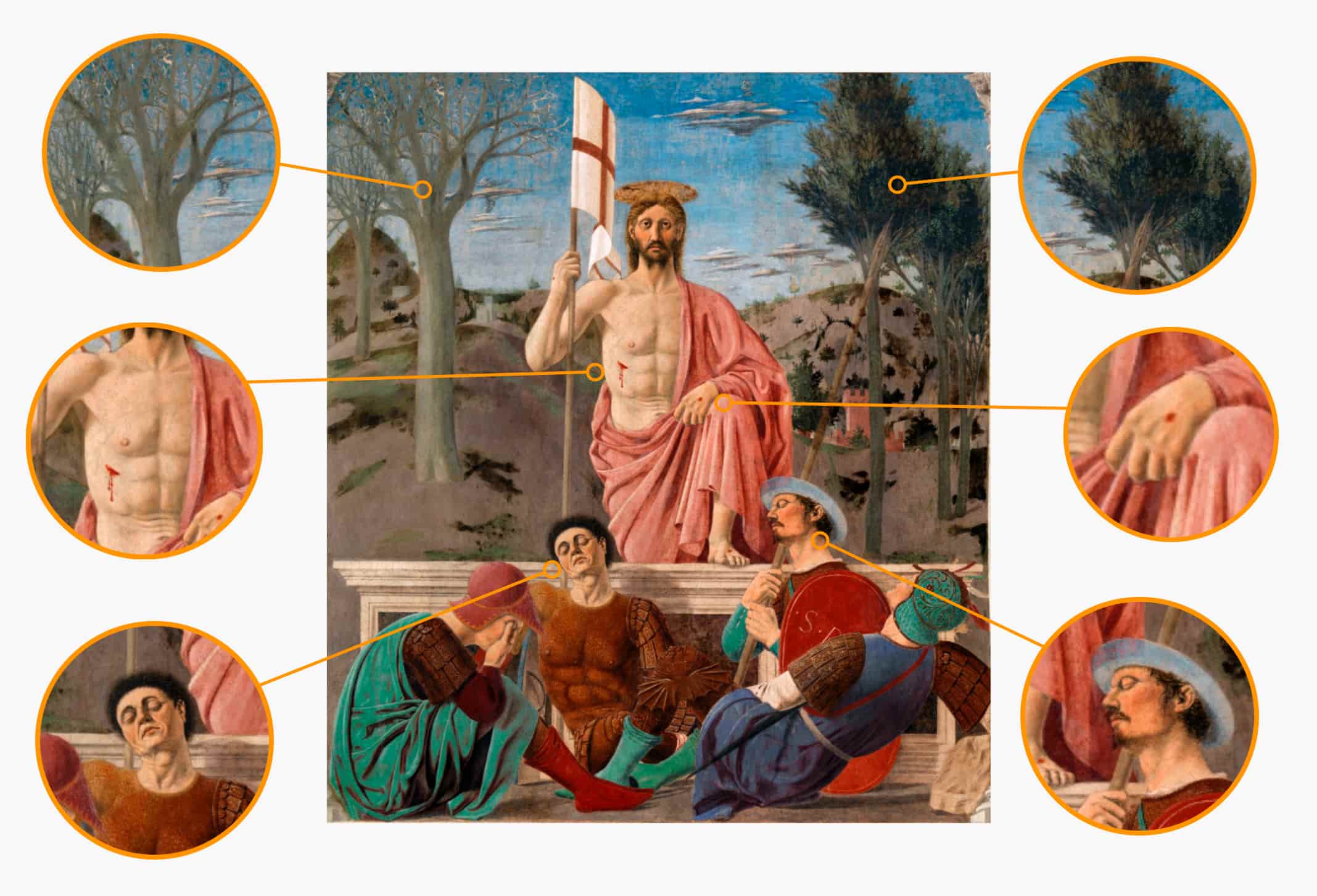

This large fresco depicts the Resurrection, the central moment of the Christian faith, with a vision and structural arrangement of the scene that is quite different from many other works reproducing the same subject.

The narrative is set within a painted frame that, with its fluted columns, unmistakably recalls classical architecture. The entire scenic construction follows an extremely rigorous, almost mathematical order.

The sleeping guards, lying at the foot of Christ’s marble sarcophagus, are positioned in such a way as to create the base of a perfect triangle, whose summit coincides with the face of the Risen One.

Most likely, the guard in the brown robe, directly beneath the victorious banner held by Christ, is a self-portrait of Piero della Francesca himself.

In this way, the artist is present at the described moment but not truly: like the other guards, his eyes are closed, overcome by sleep, and thus he does not witness the Resurrection, just as described in the Scriptures.

Christ is depicted nude; his muscular body follows Greco-Roman artistic canons, and he is draped in a cloth that, though red, lacks the scarlet intensity found in other works. Instead, its lighter hue signifies that the power of the Risen Christ here is not expressed in terms of kingship, but divinity. On Jesus’ body the marks of his Passion are clearly visible—traces of Good Friday—but without the agony of the Crucifixion. That suffering, though indispensable for fulfilling the salvific mission, has already been overcome.

Christ steps out of the tomb, his earthly experience now complete. Yet the positioning of his legs conveys the deeper message of the work: the leg flexed atop the sarcophagus suggests his thrust toward heaven, while the other, still inside the now useless and empty burial place, anchors him to this world and this dimension—symbol of the God who remains beside humankind until the end of time.

Even the natural background is not a mere decorative filler, but an image of the passage from death to life. On Christ’s right, a barren tree without leaves or fruit, untouched by spring, is mirrored on the opposite side by a flourishing shrub, full of leaves and promising new growth and fruit. This is a clear symbol of springtime—the season in which Easter is celebrated, and which, according to ancient belief, was also the time of Creation.

All these elements express a conceptual and compositional complexity far from common, and indeed many art critics have studied and described it, including the English writer Aldous Huxley, who in 1924 called Piero della Francesca’s fresco “the greatest painting in the world.”

His words later had an unimaginable consequence. Huxley’s book was read not only by art lovers but also by British captain Anthony Clarke. In the summer of 1944, Clarke received orders from the Supreme Command of the Allied forces to destroy the city of Sansepolcro, just as had already been done at Montecassino.

Although Clarke knew he had enough shells at his disposal to carry out the operation swiftly, he chose—at the risk of being court-martialled for insubordination—not to destroy the town, which had in any case already been evacuated by Germans and Fascists.

At first, Clarke explained his decision by saying that a local boy had confirmed the evacuation. In truth, he decided to spare the city after recalling Huxley’s words about Piero della Francesca’s masterpiece. Clarke realized he could never allow himself to destroy Resurrection, along with Sansepolcro.

Once in possession of the city, the captain spent an entire day standing before the fresco. We know his thoughts well, as he recorded his decisions and emotions in a diary, whose pages were shared after his death.

In his personal memoirs, Clarke wrote that, years later, he wished he could have contacted Aldous Huxley to tell him of the power of his book, of his words—summed up in a phrase that well describes the essence of art: “The pen is mightier than the sword.”