The last judgement of Michelangelo Buonarroti

How Michelangelo created the last judgement.

It is amazing how the mind and hands of artists make abstract and elusive concepts visible. I’m talking about all those stories whose origins are lost in the mists of time: mythological stories, religious testimonies, legends, which although familiar in terms of knowledge, lack a real visual concreteness.

The images chosen by artists to convey their thoughts, their inspiration regarding these stories, become something possible, even real, for us observers. Perhaps it is thanks to these numerous testimonies that have always accompanied us in a more or less conscious way that concepts that are difficult to understand, as they are far from our daily life, become less cryptic and even, as already mentioned, familiar.

Let me give a concrete example: each of us has a certain image with which to evoke the moment of creation, yet none of us have witnessed the birth of life, whose complex dynamics of development have been explored conceptually by almost all religions even before being theorised through rigorous scientific studies. It is precisely thanks to this transposition and religious theorisation of concepts that true masterpieces of art were born, which gave us the feeling of having somehow witnessed the most mysterious moments in human life. This feeling, combined with a question of personal taste, led me to choose to speak of Michelangelo in the past, examining that image celebrating the mystery of the birth of life: the creation of Adam.

The numerous and varied creations of the artist allows me to observe another moment shrouded in mystery: the last judgement, which in fact presupposes the end of the wonderful creative process examined in the previous article Like Rings in The Water: Dante’s impact on Michelangelo. As in the case of the fresco of creation, this too was made for the Vatican, therefore under papal commission, in particular that of Pope Clement VII.

How Michelangelo created the last judgement

Placed on the wall behind the altar of the Sistine Chapel, this work, like almost all those signed by the master Buonarroti, is universally known. The fresco was requested by the pontiff to conclude the biblical accounts and stories of the apostles already present in the chapel. In addition to being already involved in many construction sites, the artist was no longer very young, yet he still accepted the challenge. Upon the death of Pope Clement, the commission was renewed to Michelangelo by the new pontiff: Paul III Farnese.

The realisation of the work involved difficult choices, which were not directly linked to his genius as an artist. One of the main challenges, in fact, was having to make room for the majestic fresco. Buonarroti opted to have images already present on the wall destroyed and this was followed by a quarrel with Sebastiano del Piombo who until then had been a precious collaborator of Michelangelo. Sebastiano, assuming a lack of strength of the now elderly master, with the support of the Pope, had the wall prepared not for a fresco but for an oil depiction. Michelangelo did not even take this working hypothesis into consideration and had the preparation, which had already been made, destroyed in order to make room for the arriccio, the necessary basis for the fresco technique. Michelangelo was not prepared to let his advanced age limit his expressive genius, irrespective of what others assumed.

The artist spent 450 working days to finish the work

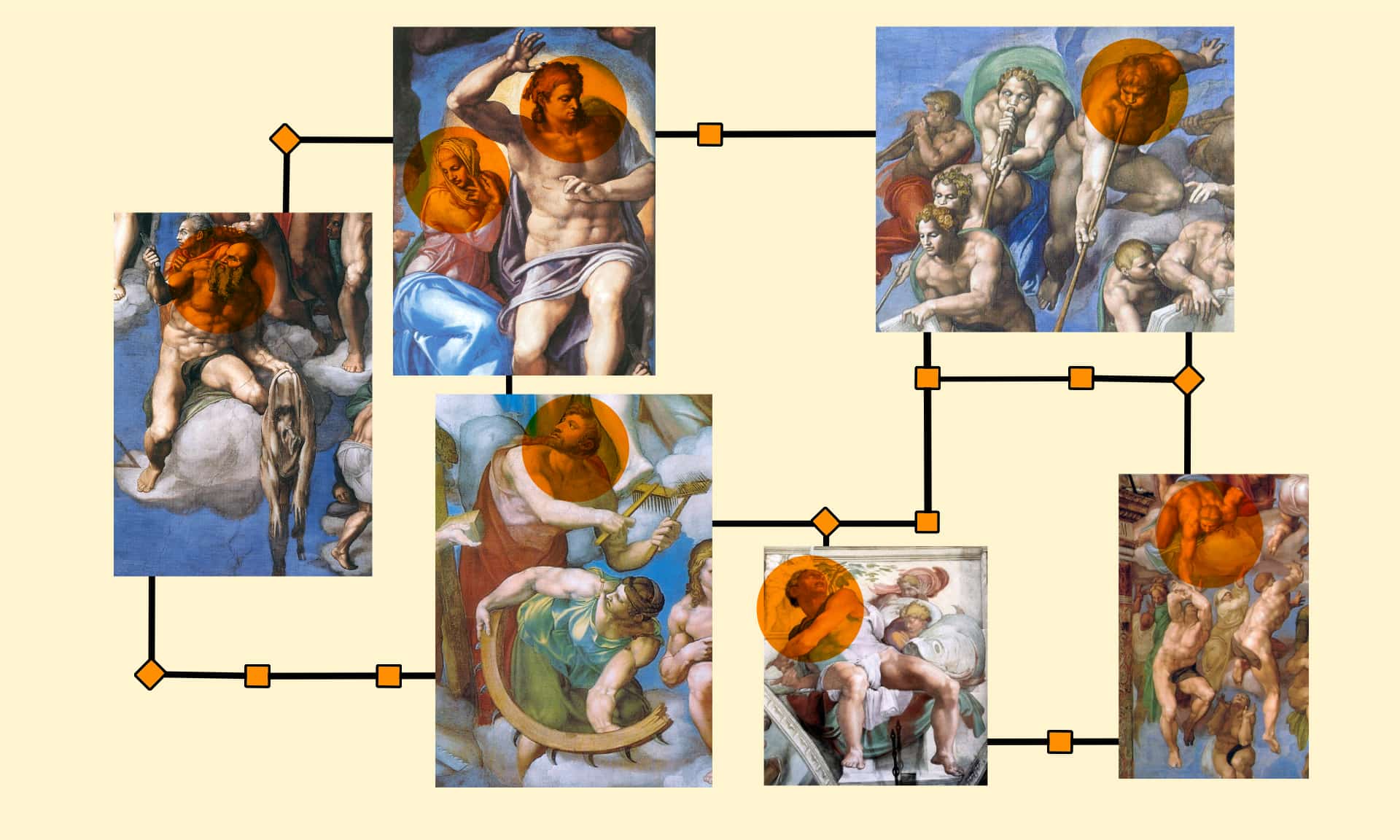

In fact, Michelangelo, apart from the help of attendants who worked to prepare the colours, worked alone on the creation of this fresco. He climbed the scaffolding to begin his work during the summer of 1536 and finished it in 1541. The artist spent four hundred and fifty working days (the duration of which was actually quite limited because it was linked to the fast drying times of the wall), working in horizontal bands from bottom to top. In addition to the imposing dimensions, the grandeur of the fresco was also obtained thanks to a novelty in the setting of the overall image that does not appear limited by frames or divisions, but expands on the wall without being contained or delimited by obstacles.

On the left the cross while on the right the column of the flagellation.

Every single element contributes to creating perfection and greatness

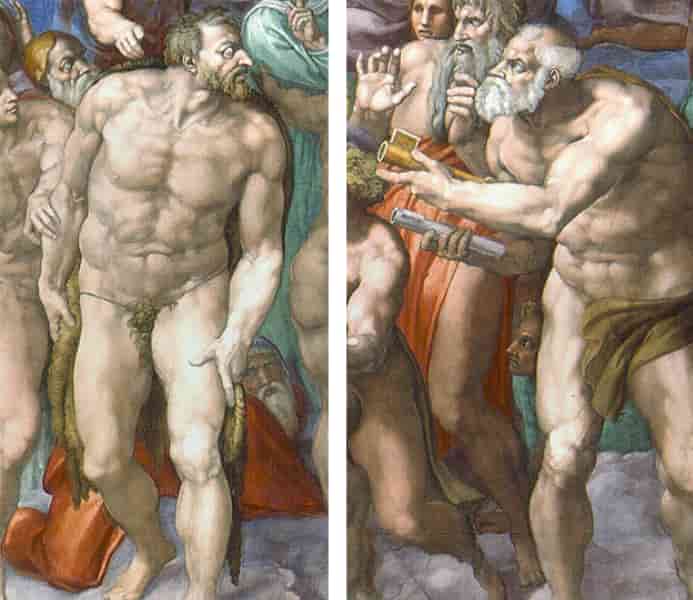

Within this huge space, figures of various sizes are inserted, depending on the position they occupy. The largest ones that exceed two metres are placed at the top, while the other smaller ones, which are about one metre and fifty in length, occupy the lower part of the wall. Observing a work of art live is always an experience that is perceived as an epiphany, a manifestation of thought and feeling and the overwhelming emotion in front of the universal judgement is just this. There is the awareness of grasping the maximum expression of a thought. Each character is clearly part of an overall discourse, but each could have an independent existence with respect to the context of the work. Each face in fact lives and transmits its emotion, its story. There is a great sensation of movement, in the intricate ups and downs along the wall, to the point of having the sensation of witnessing, and even taking part, in a tumult that is not only an inner tumult of the subjects depicted, but a whirlwind of mostly naked bodies.

The scene, clearly of a religious setting, is in fact a pictorial transposition of John’s Apocalypse, but at the same time it is a symbol of the eternal struggle between good and evil. A fight that physically manifests itself in the lower part of the scene, where the souls are flaring between angels and demons. However, it is also and above all an inner struggle, as is clearly evident from the tormented expressions of the souls awaiting judgement. The subject of the Apocalypse had already been widely “told” by mediaeval artists, yet Michelangelo’s interpretative key is so different that it is almost an absolute novelty.

In fact, the scene is seen from the eyes of a man who had lived the Renaissance in an active and conscious way, and who was now fully experiencing the historical and intellectual changes of his time. Furthermore, we must not overlook the fact that Michelangelo, who was a well-rounded intellectual whose culture covered every field, was able to bring the “modalities’’ of one of the masterpieces of secular literature: Dante’s Divine Comedy into the picture.

Read more: Dante’s impact on Michelangelo

Indeed, one of the figures in the fresco probably represents the great poet himself. In fact, it is from the description of the three kingdoms of Dante that the setting of the entire scene is most likely born, which instead of dwelling on the representation of faults, as was the norm in the past, focuses on the awareness of guilt.

Last judgement analysis

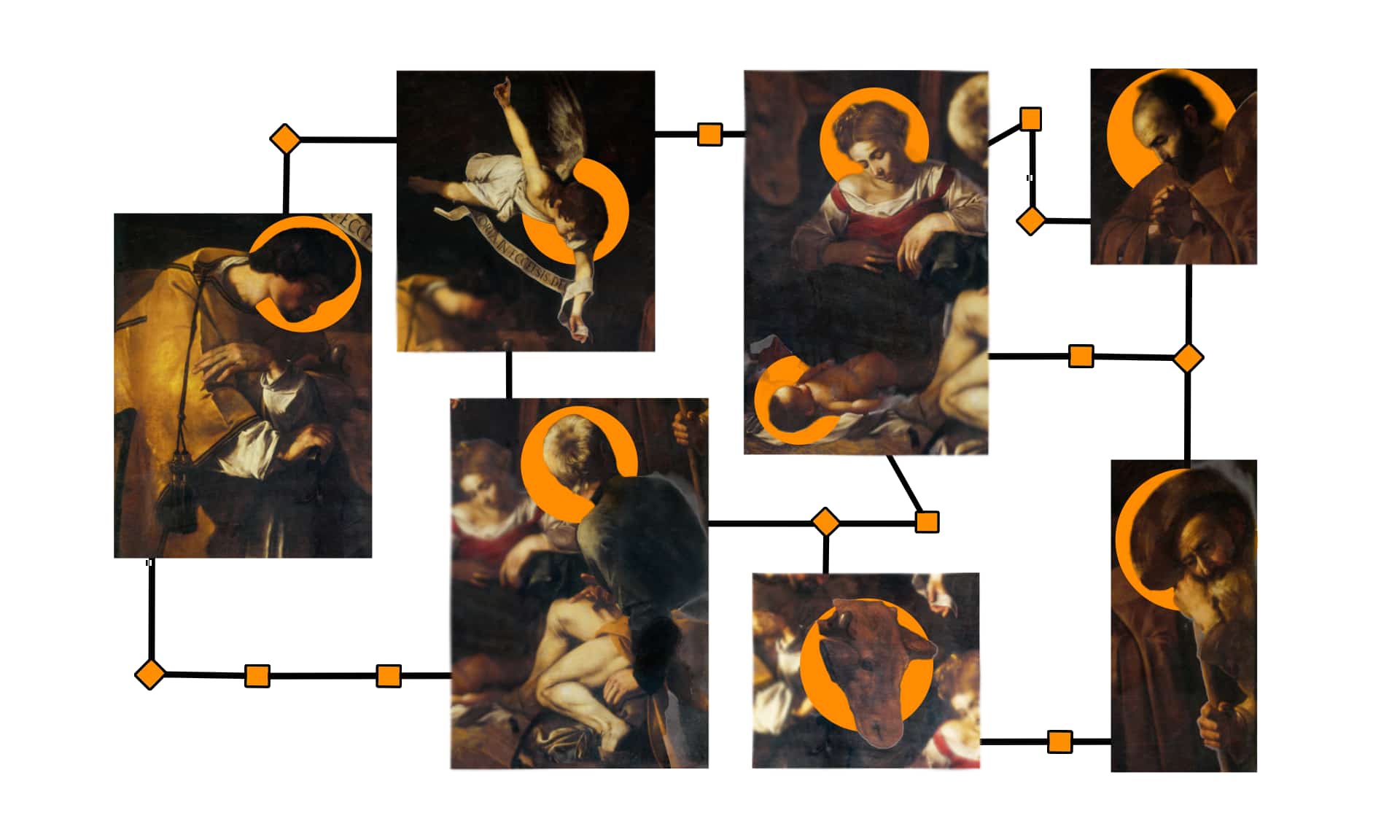

For a simple observer the scene appears immediately for what it is, without necessarily needing explanations or interpretative mediations. In fact, the main message is widely expressed through a skilful use of gestures and, as already mentioned, in every single expression of each of the characters (about four hundred figures). Obviously the master Buonarroti has left nothing to chance and despite this basic intuitiveness, there is a precise interpretation: as for the reading of a text, the fresco must be examined starting from the top left.

The first figures you meet, those that as already indicated above exceed two metres, are depicted inside lunettes and represent angels in flight or in any case suspended in the air, which support the instruments of the passion of Christ: on the left the cross , while on the right the column of the flagellation.

Jonah painted above the High Altar

Furthermore, we must not forget the figure represented outside the main scene, at the intersection of the two lunettes that contain the angels, because in this space, seated on an architectural detail, we find the prophet Jonah represented. He is easily recognisable because depicted next to the sea animal in the belly of which he had remained for three days. These three days and three nights of Jonah are a symbol of the resurrection of Jesus which took place on the third day after his death. All these elements have been represented to highlight the true protagonist of the judgement scene which is Jesus, placed at the centre of the fresco, with Mary, his mother. The two are enclosed in the typical almond-shaped space very often reserved for them. In this case, however, the almond is not depicted through architectural elements or lines, but is made using the curvature of the bodies depicted on the right and left of the characters framed here.

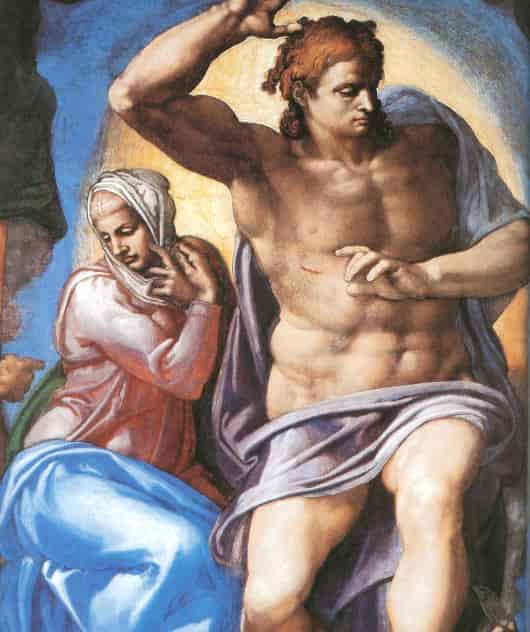

Christ and Mary

Christ, as judge of humanity, is depicted with a setting that is far from traditional Christian iconography and closer to classical sculptural language. The body of Jesus appears in fact with the physical characteristics of the heroes of classical literature, muscular and with an authoritarian air. Every gesture is specially designed to emphasise his muscles, without losing sight of the elements of faith. The arms of Jesus in fact, thanks to their different inclination, highlight the wounds inflicted by the nails and therefore his passion, and it is precisely by virtue of his divine nature and his sacrifice for men that he is now in judgement and as such his expression can only be severe.

Mary, his mother, is beside him. She is both near and far at the same time: the head of the Virgin and her gaze are in fact opposite to those of her son. This inclination balances the scene, but above all it expresses a deep awareness, because Mary is experiencing a moment in which she can no longer intercede for the souls who turn to her. It is the final judgement and this rests on her son alone.

On the sides of the central almond a host of saints attend and take part in the moment; many of the saints depicted are holding the instruments of their martyrdom in their hands. Souls are ascending to the top despite the demons who until the bitter end try to block them and to drag them down. Under the central almond a group of angels announces the arrival of the Apocalypse with trumpets, at this sound the bodies of the dead leave their tombs.

I find that even here, in this last section of the fresco, every single expression is an authentic masterpiece. In fact, all the wonder of those who awaken from the sleep of death shines through and there even bodies that are not yet clothed in flesh. The tumult of the lower floors is different from that of the upper part of the fresco, because it is full of anguish given the strong presence of demons. It is in this section that Charon’s boat is also depicted, portrayed in the act of ferrying souls of the damned while he beats them violently.

Right: A group of saved souls. Left: Charon and his boat of damned souls

The vision of this fresco, has aroused many arguments and conjectures, but it would be impossible to cover them all here, so I will only focus on some of the pictorial elements that have always fascinated me.

Where is Michelangelo’s signature? One of the features that stands out is the “signature” of Michelangelo which, interestingly, is not written but represented. In fact the artist has left a memento of himself within the scene in the detail of the skin that Saint Bartholomew holds in his hands.

Some critics have expressed some uncertainty about it, but for me there is no doubt that it represents Michelangelo; firstly, because the face depicted on the skin corresponds to other images representing the artist, and secondly, because Michelangelo, who always paid attention to the details of every single muscle of his characters, would certainly never have painted a bald Bartholomew, holding an image that was supposed to represent him, with hair on his head (his martyrdom involved being skinned alive).

Examples of the censored parts.

Was the last judgment censored? Another element that I judge to be really important is only partially linked to the observation of the work; it relates to the considerations and events that have accompanied the masterpiece over the centuries. The fresco that each of us admires today was, in ancient times, seen as a cause for shame. In fact, from the moment the scaffolding was removed, there were those who marvelled at the complexity of the layout, and those who, on the other hand, shouted “scandal!” for nudity depicted. After Michelangelo’s death, his work was subjected to censorship. The naked bodies were covered by drapery which was only partially eliminated during recent restorations. This is certainly the point that has always struck me most, because I firmly believe that this censorship, certainly the daughter of the narrow-mindedness of the time, is above all the daughter of a totally wrong way of understanding the work.

The idea of final judgement can only be rendered through nudity.

In the course of their lives, people try to dress up their weaknesses in an obstinate search for external decorum: a perfection of form which, however, too often is not a perfection of substance. This decorum, or rather this show of it, built with attention and clear awareness throughout one’s life, fades at the moment of judgement. When we are no longer the judges of ourselves, this charade is swept away by the truth that makes us naked in front of our deep nature and the tally of our actions.