The Story of My Great Uncle Pamfilo of Magliano

Pamfilo of Magliano (Giovanni Paolo Pietrobattista) was a Franciscan friar who lived a life characterised by intelligence, determination, and resilience, writes Carla, Giovanni’s great niece.

The story of Giovanni Paolo Pietrobattista, although chronologically distant, are incredibly close, because their protagonist was my great uncle. Despite never having met Giovanni Paolol, he is very dear to me thanks to the stories my grandmother and my father have shared with me. Nor only have they instilled in me admiration for what my uncle had been able to achieve, but also a strong affection and empathy towards him.

I really care about this story and though I know what I want to relate, I have stopped and started so many times that I feared I would not finish it.

My initial idea was to draw a personal picture of the history of Giovanni Paolo, but then I felt it was right to insert some historical information in order to give the right objectivity that every study, intended for common reading, deserves.

So, to broaden my knowledge, I typed my uncle’s name on the internet to look for other data to add to those already in my possession. A sort of synthesis of the religious life of Giovanni Paolo came out which presents him as an exemplary Franciscan. The adjective ‘exemplary’ kept coming back to me more than I would have liked, but ultimately I think it encompasses much of what he was.

Giovanni Paolo lived a life between tradition and innovation, with originality and awareness, in a way that offers an example to everyone. His story is not only a window into the past, it is above all a light for the future. His was an existence characterised by intelligence, determination and resilience; qualities that should accompany anyone with dreams for a better future.

The early life of Giovanni Paolo

A plaque dedicated to Panfilo da Magliano. Photo: Marica Massaro

Giovanni Paolo was born in Magliano dei Marsi in Abruzzo, in the same house that I now live in, on April 12, 1824, and he passed his youth in a rather serene family atmosphere. He immediately manifested a great intelligence, curiosity and open-mindedness that led him to undertake a personal path that I would define as both traditional and revolutionary, particularly with regards to some of the uncommon subjects that he decided to pursue.

Giovanni Paolo’s meeting and associating with the Franciscan community in Magliano dei Marsi at an early age proved life-changing. The friars resided in the convent of San Martino, where they managed what in ancient times was the most important religious establishment in the vicinity.

In this structure, no longer in existence due to the massive earthquake that rocked the area in January 1915, the friars welcomed and gave assistance to anyone in need. The charisma of the friars that brought them close to the whole community, inspired Giovanni Paolo to become part of the Franciscan order.

Pamfilo was an appropriate name he choose for his new life

On July 5, 1839, my uncle began his journey in the Province of San Bernardino da Siena in Urbino, choosing the name of Panfilo for his new life as a member of the clergy. This name of Greek origin is composed of two terms: pan, which means everything and, philos, which means friend: indeed, friend of all or, benevolent towards all. Never was a name more apt, given the subsequent history of Panfilo.

Once he became a friar, Panfilo immediately received the chair of Philosophy and Theology at the convent of the order and remained teaching in Urbino until 1852, when he was invited to go to Rome as secretary of the Minister General of the Franciscan Order.

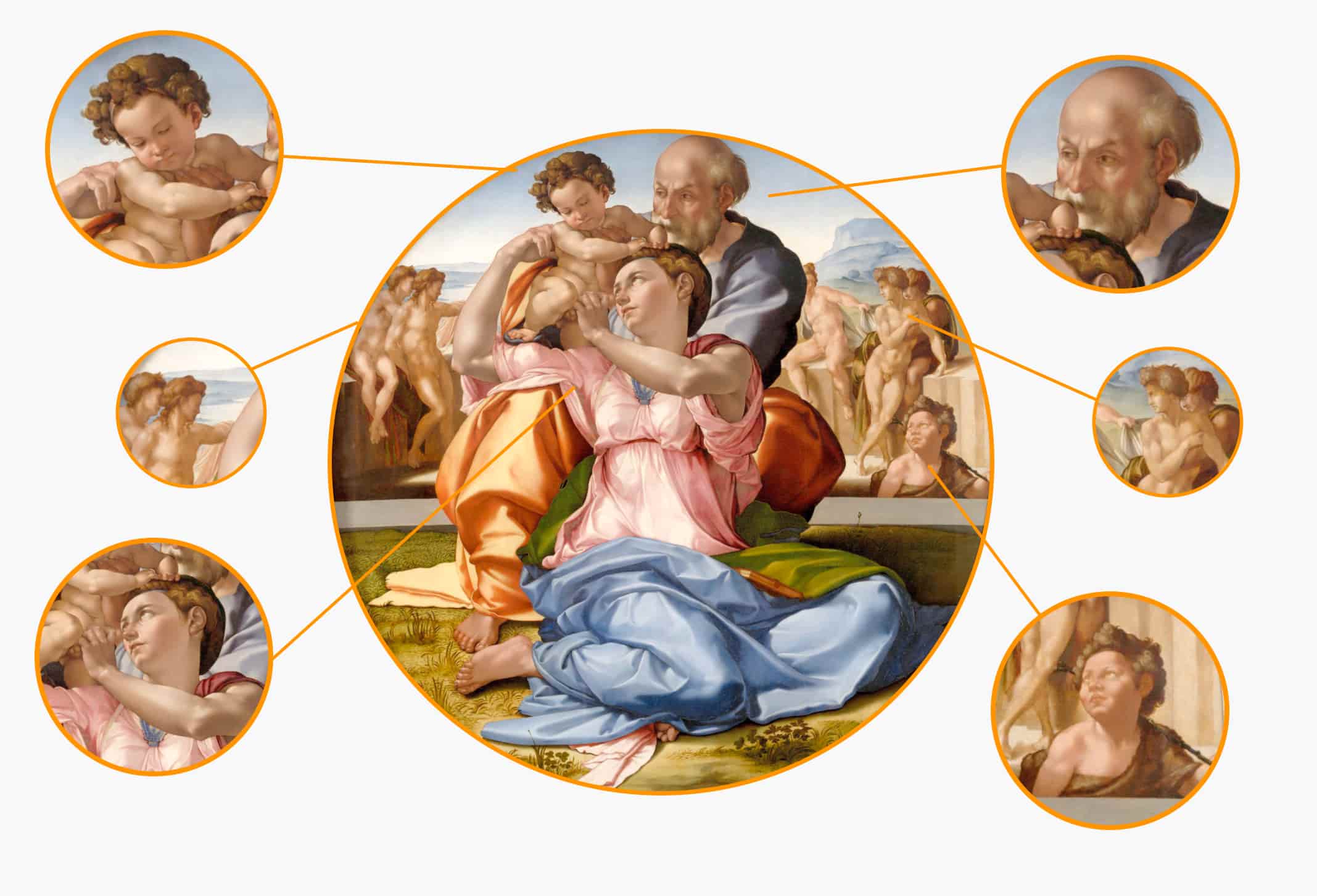

The Franciscan religious orders were established in the early 13th century by Francis of Assisi and are part of the Catholic Church. The order is open to men, women, and both genders and follow the spiritual practices and teachings of Francis and his associates. There are also Protestant Franciscan orders. Painting: Saint Anthony of Padua Taking the Habit of the Franciscan Order. © Public Domain

By December 8, 1852, Panfilo was teaching both philosophy and theology at the Irish College of St. Isidore in Rome and he remained there until January 4, 1855. During this period, Uncle Panfilo was able to improve his knowledge of English, whose rudiments he had already picked up on his own initiative.

Nowadays knowing and speaking English is certainly not uncommon, but in those times the study or knowledge of this language was not so widespread outside the British Empire. In Italy most academics dedicated themselves mainly to the deepening of classical languages, or to the study of French.

Giovanni Paolo, however, understood that for him the knowledge of this language was fundamental. It was precisely the perfect command of the English language that allowed Panfilo to pronounce the most important word of his life! A simple ‘yes’, pronounced without hesitation, to a request that came all the way from America.

Immigration to America

Portrait of John Timon, the bishop of Buffalo. © Creative Commons

The bishop of Buffalo, John Timon, needed additional support in order to be able to assist the American faithful and above all the new faithful that were arriving from Europe.

Bishop Timon found himself presiding over his community in a historical moment of great social and cultural transformations, during which millions of men and women, due to various emergencies, mainly of an economic nature, were forced to leave the old continent to seek their fortune in the Americas.

From Italy alone, for instance, more than four million people landed in the United States between 1880 and 1915, while a constant flow of Irish had been immigrating to America in search of new opportunities since the potato famine that struck their country in the 1840s.

To meet the multiple needs of the growing number of Catholic migrants, Bishop Timon turned directly to Rome, and in particular to the friars of the Irish College. This was partly thanks to the support he was receiving from the Irish Nicholas Devereux, a man who after leaving his home country had become a successful financier and banker in America.

Most likely the request for help did not obtain the result imagined, because the ‘yes’ to this call did not come from an Irishman, but from a young Italian full of hopes and dreams, together with the strength and faith to transform them into reality. This was precisely Father Panfilo from Magliano.

Panfilo was accompanied by Sisto da Gagliano, Samuele da Prezza and Salvatore da Manarola and the importance of their mission was underlined by the fact that the three clergymen received the personal blessing of Pope Pius IX before leaving.

Father Panfilo had previously collaborated with the pontiff, since he was among the experts who had been chosen for the definition of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception of Mary.

My uncle arrived in New York on June 20, 1855 and from there he first moved with his travelling companions to Ellicottville, where they were guests at a house that still stands, and then to Allegany in the State of New York.

It is in this city that Panfilo and the friars who were under his guidance began their mission by providing spiritual assistance to the faithful whose parishes had remained without a guide.

Notable achievements

However, Panfilo’s spirit of initiative was too great to be limited to this. My uncle founded convents, two academies and religious congregations, such as the Franciscan nuns of Allegany.

Thanks to his incessant work, the county where he worked was enriched with 22 missionary churches; five parishes and a seminary.

As far as I am concerned, though I expect that I am not alone in this assessment, the true masterpieces of Uncle Panfilo were carried out between 1859 and 1861.

In 1859 Panfilo founded, and was the president of, the Saint Bonaventure University, a prestigious college that now has more than 2,000 students.

Then, in 1861 he founded the Franciscan Congregation of Immaculate Conception, of which he was also the first superior, and which went on to found schools and hospitals in other parts of the Americas.

Panfilo also worked to involve lay women in the life of the order, providing them with guidance and above all involving them in a school education addressed to the local population. After this, Panfilo went on to found the order of the Franciscan nuns of Joliet, Illinois in 1863, with a contribution from the town of Magliano dei Marsi.

Sudden return to Italy

A plaque dedicated to Panfilo da Magliano. Photo: Marica Massaro

Suddenly, in 1867, and without too many explanations, Panfilo was recalled to Italy. After his arrival he learned that his summoning to Italy was due to misleading information that had been provided by a jealous friar.

The misunderstanding was soon cleared up, but by now Panfilo had already been replaced and for this reason he had no way of returning to America.

Obviously, this was a hard blow for my uncle’s ministry, but he knew how to exploit other aspects of his vocation by dedicating himself to writing and translating texts. In 1870 he published The Greek Church and the Procession of the Holy Spirit from the Father and the Son and in 1874 he translated Cardinal Henry Edward Manning’s The Temporal Mission of the Holy Ghost: Or, Reason and Revelation into Italian.

In 1876 he published the first two volumes of the Compendious History of St. Francis and the Franciscans; the third volume of which was left unfinished because on 15 November 1876 he died in Rome, almost certainly due to a tumour.

I do not deny that I would have liked to look for the name of the friar who managed to get Giovanni Paolo back to Italy, but then I realised that this search would have been useless because the historical truth and the authenticity of Panfilo’s vocation, his works and the enormous cultural heritage and affection he left in America.

A legacy that I touched firsthand during a visit to Saint Bonaventure University. On that occasion I took a tour of Panfilo’s landmarks which represented a profound, almost introspective experience for me; a journey that allowed me to visit places and establishments that I had never seen in person, but that somehow felt mine, because in my own way I had already lived them through stories and research. It was like that intimate feeling of being back home.