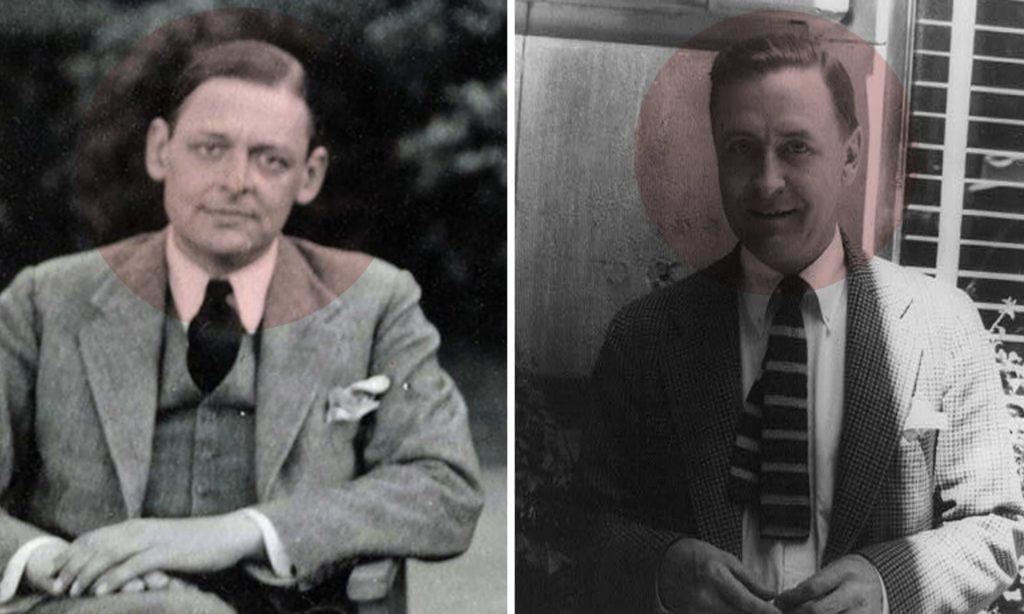

The situation that plagued the world after World War One was one of callous apathy and emotional aridity. My last article on T. S. Eliot’s poetic portrayal of the early 20th century ended with the line, “The dehumanisation of the modern world is complete.” This ‘dehumanisation’, which Eliot portrayed as a waste land in his poetry, was also described very clearly in prose by F. S. Fitzgerald in his novel The Great Gatsby.

Fitzgerald was a very different individual and a very different writer. Like Eliot he was an American, however his focus was not on the ‘Unreal City’ of London, where the inhabitants moved around like dead souls from Dante’s Inferno:

Unreal City,

Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

Fitzgerald’s characters, also morally and spiritually dead, were American through and through. They were like zombies moving around from party to party, ignoring the cultural and moral aspects of life. The author was almost prophetic, in that he gave a name to his time, the Jazz Age, and lived through it as though he were a character from one of his books.

Besides his best known novel, The Great Gatsby (1925), he also wrote four novels, The Beautiful and Damned (1922), This Side of Paradise (1920), Tender is the Night (1934), and The Last Tycoon (his last and unfinished work which was published in 1941). He also wrote five volumes of short stories, which include The Crack-Up, and a selection of autobiographical pieces.

The Jazz Age, or the Roaring Twenties, was characterised by an intense ‘joie de vivre’ that bordered on the extreme…

Extravagant parties were held regularly and fancy nightclubs, where everybody tirelessly danced the Charleston, were very fashionable. Fitzgerald captured this rollicking lifestyle in The Great Gatsby.

Naturally things changed with the Great Depression. The fleeting splendour of the twenties became a mere memory. Life turned into a struggle for survival and the country fell into the hands of the relief program. The 1929 economic slump was inevitable and Fitzgerald had prophetically foreshadowed it through his depiction of the putrefaction of the moral and social fibre of the society that had preceded it.

The Great Gatsby, The Valley of Ashes & The Waste Land

The Great Gatsby is a short novel that depicts the essence of the 1920s lifestyle and the frivolous importance society placed on money and material things. Fitzgerald managed to highlight the contrast between the grandeur and the illusion of the period. The United States, although very different from Great Britain, was undergoing the same dehumanising aridity that T. S. Eliot had so strikingly depicted in his The Waste Land.

Eliot said about Fitzgerald’s novel: “It has interested me and excited me more than any new novel I have seen, either English or American, for a number of years.”

Fitzgerald was certainly inspired by Eliot’s The Waste Land, as James E. Miller suggested: “It is possible that [Eliot] saw in The Great Gatsby a reflection of some of the kinds of images of the horror of modern life that he himself had given currency in his poem”.

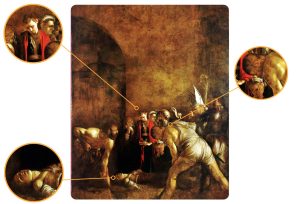

Indeed, in the novel we have the Valley of Ashes that ominously lies beyond the knowing eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg, a forgotten billboard by the side of a road. This is the same metaphorical landscape of Eliot’s Waste Land which symbolically represents the social and emotional aridity humankind has spiralled into. The Waste Land and The Great Gatsby both portray this dusty vastness where nothing thrives. The old forgotten billboard, with the looming eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg, is seen as an old forgotten God. A God who has no place in an emotionally dead society.

But above the gray land and the spasms of bleak dust which drift endlessly over it, you perceive, after a moment, the eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg. The eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg are blue and gigantic—their retinas are one yard high. They look out of no face, but, instead, from a pair of enormous yellow spectacles which pass over a non-existent nose. Evidently some wag of an oculist set them there to fatten his practice in the borough of Queens, and then sank down himself into eternal blindness, or forgot them and moved away.

Myrtel’s husband, George, believes that they are the eyes of God. He says that ‘God sees everything’. The ashes that frame those eyes are symptomatic. John W. Bicknell considered that: “This grotesque image, reappearing throughout the story, eventually becomes a symbol of what God has become in the modern world, an all-seeing deity – indifferent, faceless, blank.” This image is similar to Eliot’s Tiresias who in The Waste Land appears as the all-seeing eye, although being old and blind.

I Tiresias, though blind, throbbing between two lives,

Old man with wrinkled female breasts, can see

At the violet hour…

Blindness is a recurring theme in both Eliot and Fitzgerald

The Valley of Ashes, between West Egg and Manhattan, and the Waste Land in the “Unreal City”, make up the humus of both works. The characters are all hovering around aimlessly within a lifeless existence. The backdrop is a barren expanse in which they bump into each other in a human cycle of blindness. The absence of morality and spiritual values together with apathy and indifference create the stage on which the characters of both texts perform their robotic actions.

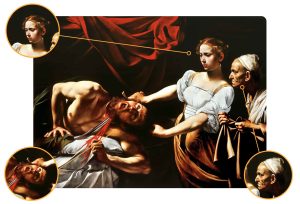

Both authors emphasize the grandeur of past civilizations, in Europe and in America, to contrast the squalor of modern life. The past is gone and will never return, however much Gatsby wants it to. Nick tells Gatsby, “You can’t repeat the past,” Gatsby replies, “Why of course you can.” Gatsby’s belief that he is able to repeat the past simply substantiates his disconnect from reality. Gatsby’s house is often compared to that of a feudal lord. His foreign clothes, antiques, and furnishings all suggest a nostalgia for the British aristocratic lifestyle. This dream of returning to a glorious past, however, results in a superficial imitation of the old European social system that America had left behind.

Gatsby’s tragic end is the inevitable outcome for all those whose belief lies in materialistic wealth and blind social climbing. Only an ‘old’ established reality can survive in this scenario, people like Tom and Daisy Buchanan. They are unscathed and invulnerable because they do not need to search for material wealth due to their inherent class privilege. However, Fitzgerald clearly suggests that the American society has fallen prey to the dictates of modern squallor. Tom’s immoral behaviour and the general debauchery of the upper classes highlight the breakdown of past values.

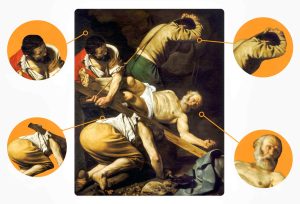

For society to survive, Fitzgerald points out, it must strive for a new social order with the objective to overcome the decadence of American cultural and moral values. By both vanquishing and remodeling the past, humankind may eventually reach its haven.

Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther. . . . And one fine morning— So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.