English Poetry After WWII: The Rise and Evolution of Post-War Literature in The UK

In a world recovering from the devastation of war, how did English literature find its footing? Here are the most pivotal figures and movements that reshaped the post-war literary landscape.

Post-War English Literature

As we have already seen while analysing the literary background of previous periods, the literature of each historical age often reflected the political and social situation of the time.

Post World War II literature was no different. Those terrible years of violence and devastation created a sense of general pessimism, cynicism and disillusionment.

Literature after the Second World War clearly portrayed man’s disorientation, which was not only evident in the content of literary works but also characterised by the absence of one specific major school of thought or movement.

Writers were closing in on themselves and, although showing no signs of extreme innovation, they tended to be more individual in their search for something to say. The playwright Arnold Wesker complained that those who had so much to say and so much to fight for, were “a harmless wave of nothing but lukewarm, delicate air”.

The poetry that was written in this period showed no obvious or remarkable innovation. However, the sensitivity, emotional restraint and opposition to the intellectual, cerebral poetry of T.S. Eliot did create a fresh, intense and pure style.

https://un-aligned.org/culture/your-guide-to-t-s-eliot-poems/

English literature did not stagnate and was very much alive and vibrant. Although it tended to “retreat into parochialism or defeatism”, it did have its “out-standing moments of protest, defiance, honesty or insight”, as G. Phelps wrote.

Post-war poetry was more versatile than prose. Groups, movements, individualists and traditionalists all gave their contribution to the world of verse. The older poets continued to produce substantial works, some becoming aware of the new political and social situation.

Pylon Poets: Spender, Auden and Betjeman

The Pylon Poets, including politically motivated figures like Spender and Auden, were active during the 1930s. Despite their waning political motivation, they continued to write about societal problems.

These poets focused on exploring and addressing the pressing issues of their time. Stephen Spender and W.H. Auden were notable members of this group, among others, who maintained their commitment to highlighting social concerns through their poetry.

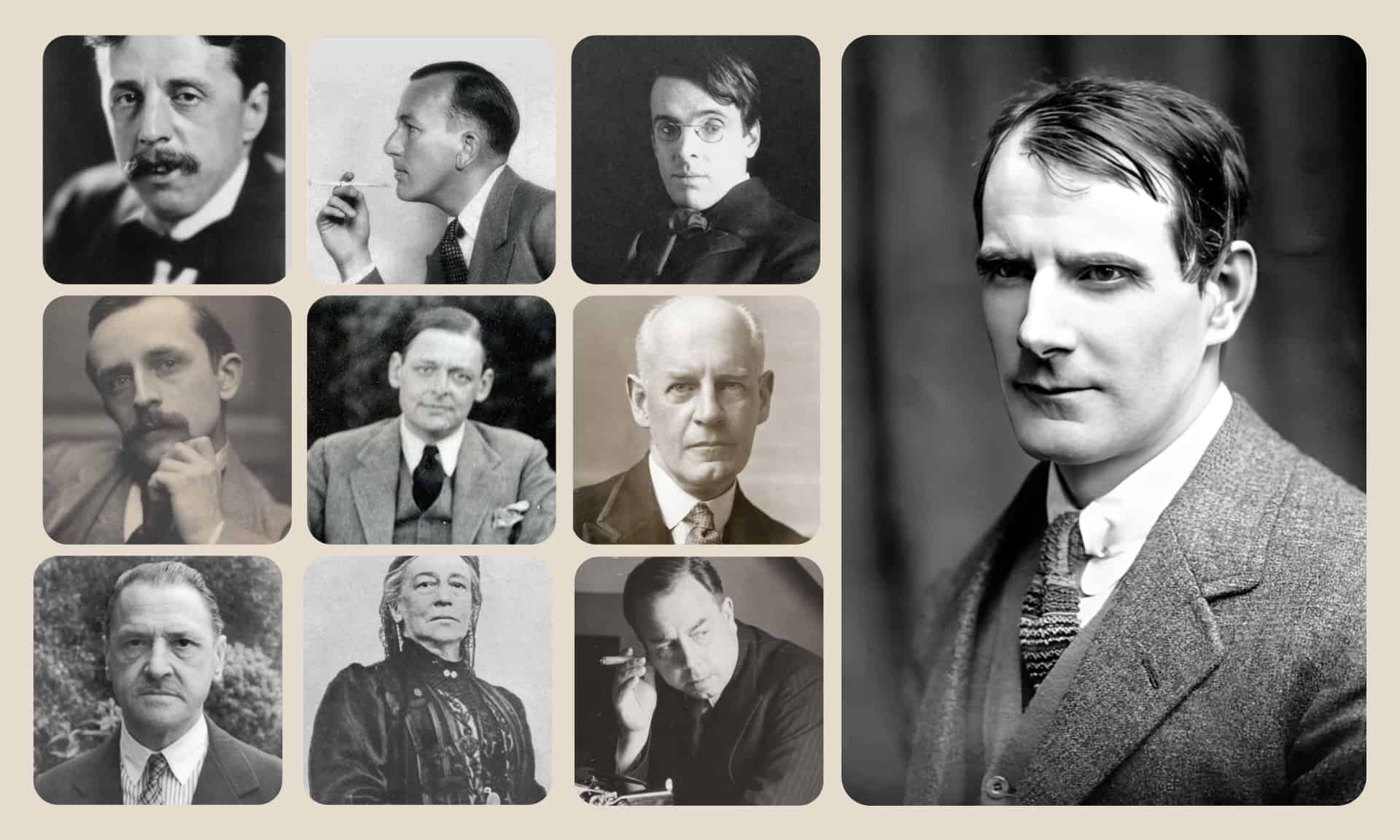

W.H. Auden, Christopher Isherwood and Stephen Spender. Photo: Howard Coster. © National Portrait Gallery. Used under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Auden was particularly concerned about the dehumanising effect of modern society. His later poems revealed a touch of mysticism as he battled with his own spirituality. His main works in this period were The Age of Anxiety (1948), The Shield of Achilles (1959) and Homage to Clio (1960).

Of the older poets, John Betjeman was perhaps the one who was most widely read and appreciated. His satirical light verse written in traditional forms and unique smooth rhythm, made him in 1958 a surprising bestseller. His Collected Poems sold over a hundred thousand copies in the original edition.

This success can also be explained by his unique ability to relate his emotions to those of his generation, who had also lived through the pre-war years. He managed to give life to the nostalgia they all felt for those happy days before the war. Betjeman became Poet Laureate in 1973.

Dylan Thomas and his transition from romanticism to social themes

Dylan Thomas, who had been writing as a so-called New Romantic, was greatly affected by the Second World War. His earlier works, during the interwar years, were subjective and personal.

In the late 1940s and the early 1950s he became more aloof and depressed. His poetry no longer revolved around his emotions on love or death, but became more varied and somewhat social.

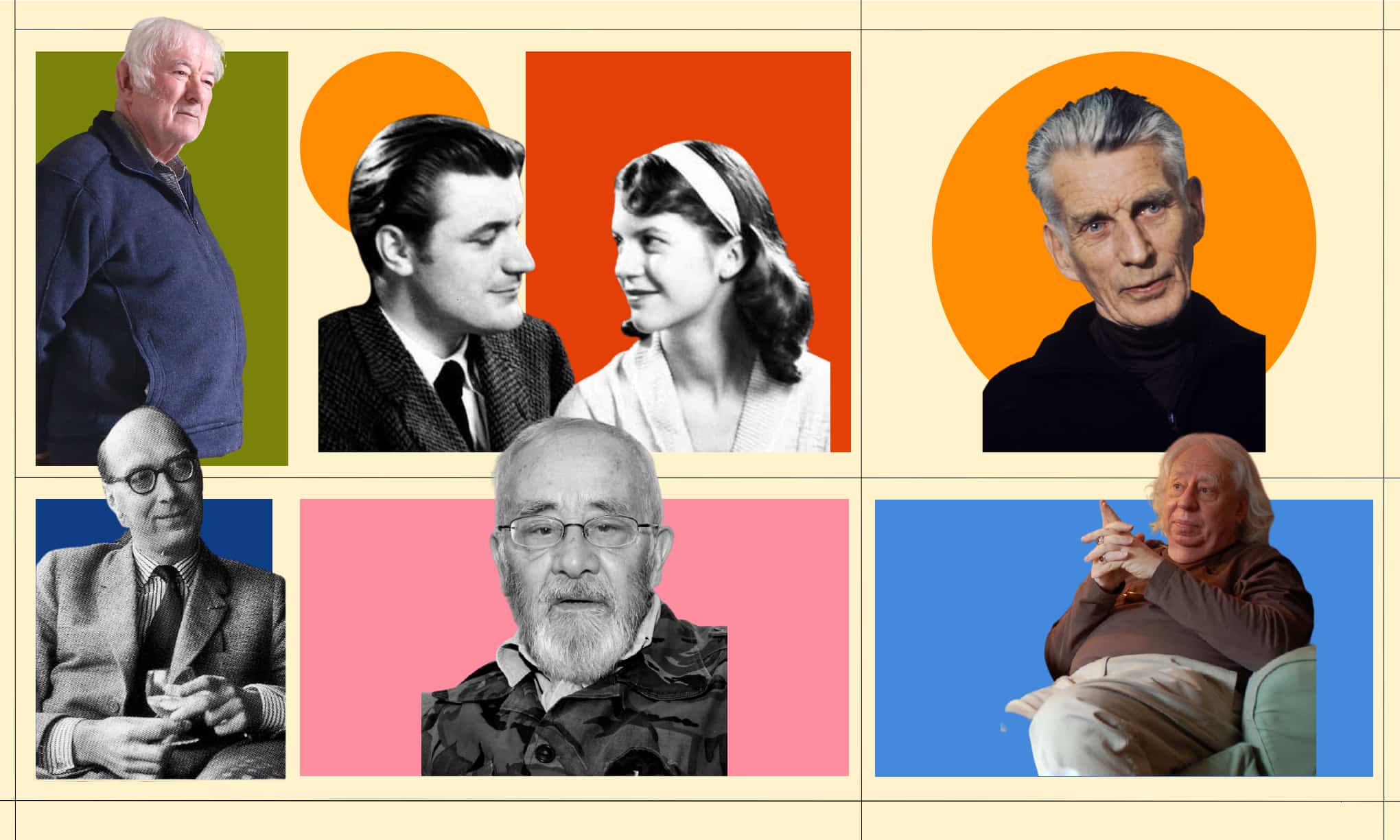

Dylan Thomas

Deaths and Entrances, for example, which was published in 1946, was an intense picture of London under the enemy bombs. Thomas also experimented with different styles and imagery.

He often contemplated pre-war life, considering death as a viable solution to his present anguish. After the war, in 1949, Thomas had a dream, which Dannie Abse recounted in a BBC television programme about him on April 9th, 1976:

“He had floated into a large unlit cave and there saw Job smitten with boils […] that cave led into another, and that one into yet another, and back and back in time Dylan wandered in his dream, seeing one biblical scene after another […] until he wandered right back to the darkest cave of all, the very first one, and then he saw a man and a woman hand in hand.”

“I doubt if this was a real dream, but it does illustrate the direction of Dylan Thomas’ imagination, a journey back to paradise.” — (Penguin Literary Biographies- Paul Ferris)

This ‘journey back to paradise’ was, in a way, a common trait in most postwar poetry, which was continuously searching for solutions it could not find.

The Angry Young Men

The literary school called The Angry Young Men was formed by writers who were writing within different genres of literature. The term, taken from Leslie Paul’s work, Angry Young Men, described all those playwrights, poets and novelists who expressed their anger and sarcasm at the emerging social friction between classes.

https://un-aligned.org/culture/the-rise-of-the-angry-young-men-in-british-drama/

The writers who best captured this sense of frustration were undoubtedly Kingsley Amis, Alan Sillitoe, John Braine and David Storey. The main themes of this school were cultural and political disillusionment; a feeling that culture had fallen to a level of degradation, becoming almost pseudo-culture.

One of the best works of this type was Lucky Jim, written in 1954 by Amis.

The Theatre of the Absurd

The playwrights of the Theatre of the Absurd managed to shift the focus from plot and structure, to surrealistic illusion and self-expression. The two giants in this field were Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter.

Samuel Beckett is best known for his masterpiece Waiting for Godot (1952), a play that shocked the traditional critics who desperately searched for plot, characterisation, orchestrated dialogue or just a plain simple story, and found none. The play, on the contrary, was more of an incarnation of an idea, a spotlight on man’s loss of communicability and self-awareness.

https://un-aligned.org/culture/samuel-beckett-harold-pinter-two-giants-of-the-theatre-of-the-absurd/

Harold Pinter became famous for the Pinteresque style of dialogue which expressed the disharmony of society. He saw man as an object that simply existed. He echoed Beckett’s description of man as “a scrap of life surrounded by death, a something encircled by nothing.”

The Theatre of the Absurd illustrated chunks of dreams and nightmares, highlighting themes of loneliness, isolation and suffering in a world in which all values and ideals were lost.

The Movement: Thom Gunn and Philip Larkin

After the death of Dylan Thomas in 1953, poetry began to be characterised by a conscious break from the poets of the inter war years.

There developed an urge to rediscover, in simple and direct language, the English tradition, which had been so badly shattered during the war. The group which governed this poetic development was The Movement, an assembly of various poets who were threaded together by Robert Conquest and Donald Davie.

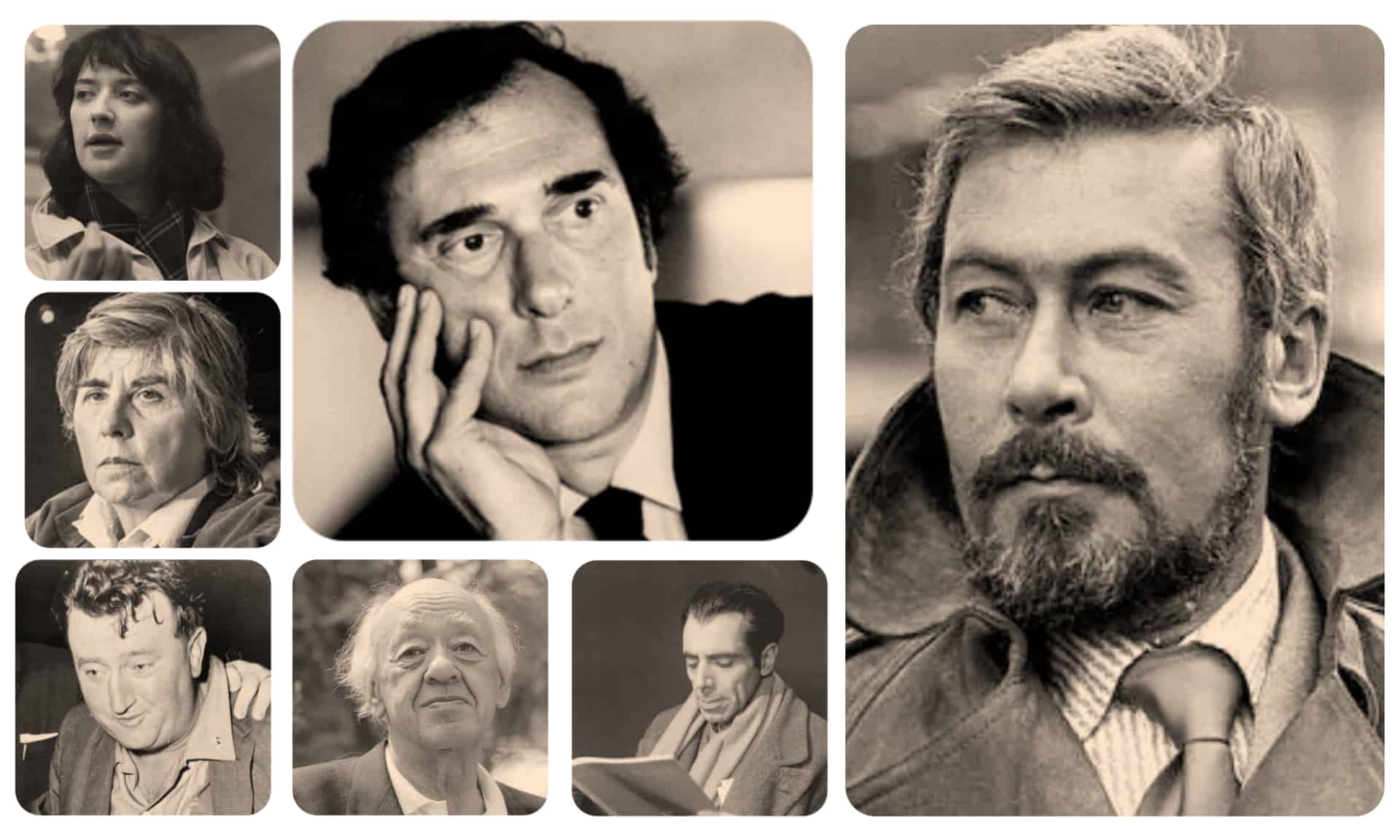

Together with these two poets in The Movement, there were Philip Larkin, Kingsley Amis, John Wain, John Holloway, D. J. Enright, Elizabeth Jennings and Thom Gunn. Gunn and Larkin are perhaps the most representative of The Movement poets.

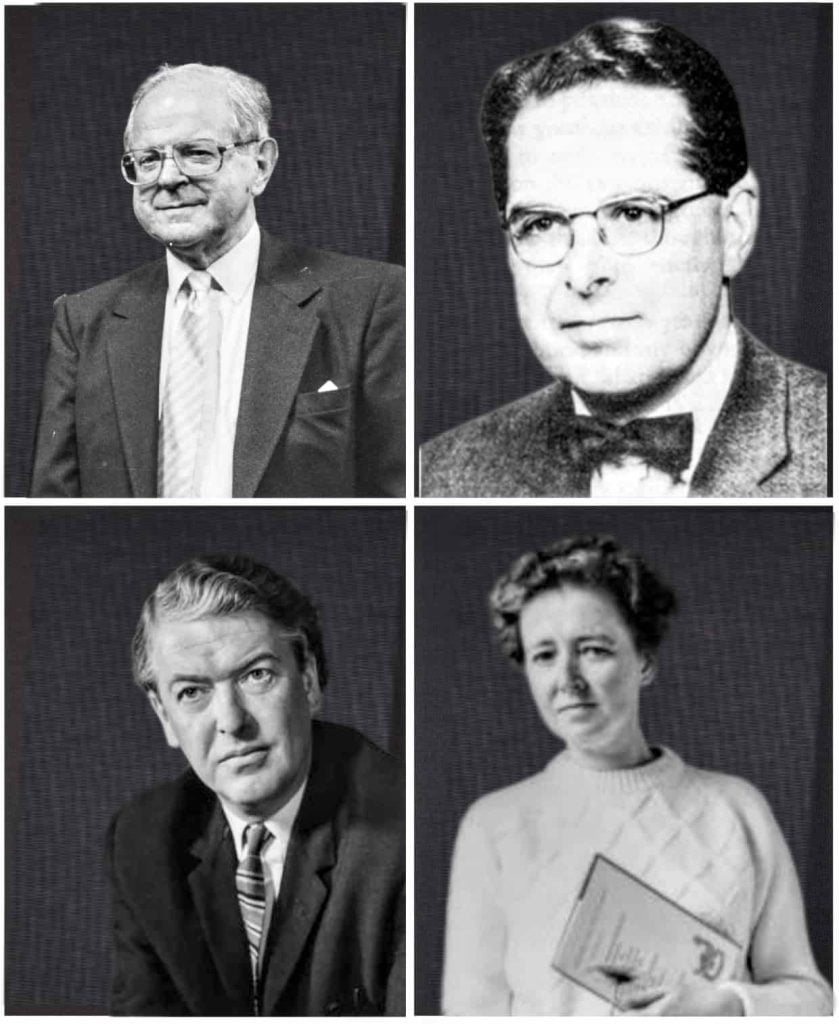

Top to bottom, left to right: Robert Conquest, Donald Davie, Kingsley Amis and Elizabeth Jennings

Thom Gunn stressed mood, intentionally creating variations of it in his different poems. While a student at Cambridge, Gunn developed a theory. He observed that everybody seemed to behave differently when dealing with different people and in different circumstances. Therefore, he believed that it would be best to be utterly conscious of this and to use direct roles consciously.

This is evident both in his first book, Fighting Terms (1954) and in his second, The Sense of Movement (1957). The poet, in his way, also studied the various sides of contemporary life. It was, however, in Gunn’s second book that energy began to work its way to the surface. His poem To Yvor Winters, written for his teacher when Gunn was at Stanford University in California, is a case in point.

Winters had helped free Gunn from prescriptive forms, first by leading him into experimentation with syllabics and finally into free verse. Michael Schmidt wrote: “Winters showed Gunn that the intensity of a poem is intrinsic in the rhythm and the tone of the speaking voice.” In this poem Gunn wrote:

You keep both Rule and Energy in view,Much power in each, most in the balanced two:Ferocity existing in the fenceBuilt by an exercised intelligence.

With these poems Gunn explored various parts of contemporary life using his theory that there was always a conscious adoption of a different pose, in different circumstances.

The pose that was particularly favoured was that of the tough non-conformist. These were the years of the angry generation, reflected in authors like Kingsley Amis, who in 1954 published Lucky Jim, a perfect interpretation of the struggles of youth in a hostile society.

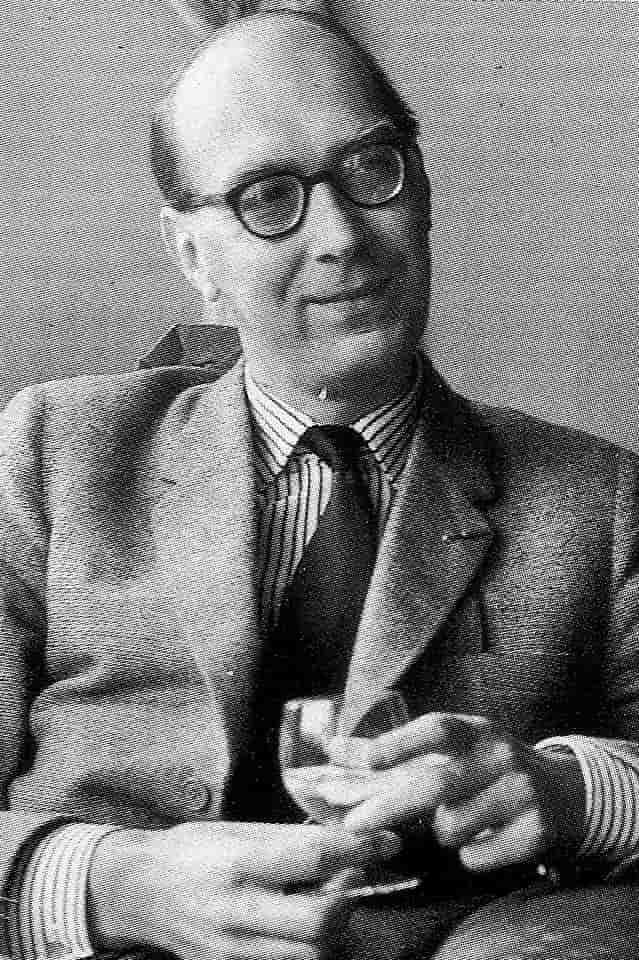

Philip Larkin © Simon Knott/Flickr

In the poem On The Move, for example, Gunn described a gang of toughs who raced their motorcycles across the landscape without a precise direction in mind. This disquiet was imbued with various symbols which dealt with life’s problems and complications:

One joins the movement in a valueless world,Choosing it, till both hurler and the hurled,One moves as well, always toward, toward.

Philip Larkin, on the other hand, can be best described with his own words.

“I write poems to preserve things I have seen/thought/felt (if I may so indicate a composite and complex experience) both for myself and for others, though I feel that my prime responsibility is to the experience itself, which I am trying to keep from oblivion for its own sake. Why I should do this I have no idea, but I think the impulse to preserve lies at the bottom of all art.”

Larkin published The Less Deceived in 1955, which clearly demonstrated that his “prime responsibility is to the experience itself’. Experience was often related to the passing of time, old age and death, themes that were recurring in his poetry.

Like Betjeman, who looked to the past for peace, or Thomas, who looked to the past for paradise, Larkin compared his present state of disillusionment with the childhood joys and aspirations of a promised happy and fulfilling future.

With Larkin, poetry completely broke from its ties with the difficult experimental verse of Eliot and the politically social poetry of the pre-war years. It was built within a lucid simple style, using metaphors and difficult figures of speech sparingly.

The Group: A Response to The Movement

In the expansive landscape of post-war poetry, an alternative school known as The Group arose. This collective, or rather, workshop of poets, was a thoughtful and defiant reaction to The Movement.

Left to right: Peter Porter, Edward Lucie-Smith and George Macbeth

The Group carved a distinct niche for themselves, representing a cadre of cultural elites, unapologetically crafting their work for a highly discerning reader.

Among the many noteworthy poets who were part of The Group, three figures stood out. Peter Porter, the Australian-born poet who imbued his work with a profound sense of irony reminiscent of John Donne, George Macbeth, whose lyrical narrative style echoed that of Dylan Thomas, and Edward Lucie-Smith, a critic and poet whose versatility and eclecticism bore a likeness to T.S. Eliot.

Ted Hughes: A Singular Voice

A poet who stood out for his individuality and who had no ties to any group or movement was Ted Hughes. His poetry was a blending of existential soul-searching with the exploration of animal life, nature and elemental forces.

Hughes’s first volume of poetry, The Hawk in the Rain (1957), was powerful and energetic, but, at the same time, graceful and lyrical. Other memorable works of his are Lupercal (1960), Wodwo (1967) and Crow: from the Life and Songs of the Crow (1970). Hughes became Poet Laureate in 1985, replacing John Betjeman who had died in 1984.

Ted Hughes

Seen as a whole, the picture presented by post-war poetry up to our days is one of striking characteristics. Human experience became the essence while epic, bombastic, heroic and tragic poetry was dropped altogether.

60s and 70s: Regionalist Poets, Eclectic Themes and Seamus Heaney

The 1960s and 1970s did not give rise to any specific poetic movements. The versatile and eclectic nature of poetry became more evident. Some regionalist poets were shifting the cultural fulcrum from London to other different cities.

Jon Silkin (1930-1997) to Newcastle, with his best work Poems New and Selected (1966), and Roy Fisher (1930-2017) to Birmingham with his Collected Poems, (1968). In this volume, Fisher portrays Birmingham with intense realism and factuality.

A poet who made a name for himself in the 1960s was Seamus Heaney. His first collection of poetry, Death of a Naturalist, established him as a well known and respected man of letters, a label which accompanied him up to 1995 when he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The literary style of Seamus Heaney is characterised by clarity and simplicity. Each word that the poet writes seems to evoke a special understanding between it and the reader.

The Times Literary Supplement once wrote of his work: “At the root of every word there is a tentacular handshake between the speaker and the thing spoken of.”

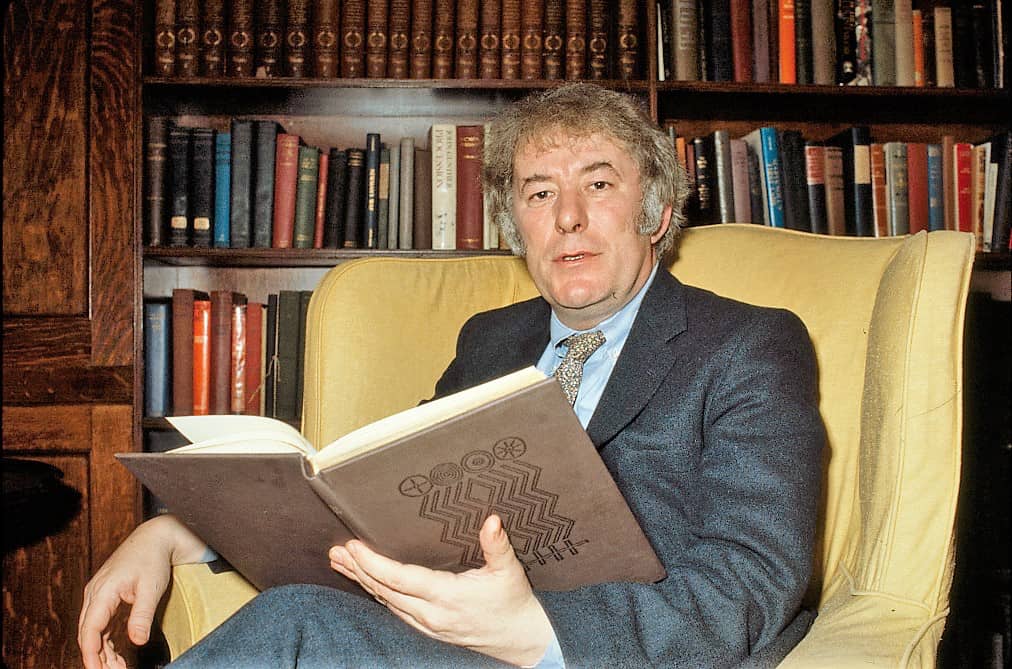

Heaney in 1982

His poems portray a particular love for Irish life and heritage, placing importance on the continuity of family traditions. The past is very dear to Heaney. He is very conservative in relation to his past and feels the need to preserve it. He believes that the past can remain, if we reinterpret it, in our present.

There is also the rural element in his work, which embraces the essence of his poetry. Even the symbolic search within himself is depicted as the rural act of digging, an inner digging within his consciousness.

His “dig” is also like an archaeological excavation into his roots. The critic Anne Stevenson wrote of his work in The New York Times Book Review.

“With an Archaeological deftness, he excavates his roots – now personal, now lost in the turf of saga, myth and history, yet sensitive always to the claims of equivalent language.”

Seamus Heaney is also a respected critic and has written various critical works on poets like William Wordsworth, Gerard Manley Hopkins and Robert Lowell. One of his best collections of essays was published in 1980 under the title Preoccupations; Selected Prose 1968/1978.

A Constantly Shifting Literary Landscape

Post-war English literature encapsulates the resilience and vibrancy of a society healing from war’s atrocities. This era bore witness to a diverse tapestry of voices and styles that offered unique interpretations of life’s experiences and societal concerns.

The landscape of literature during this period was continuously shifting, with no singular dominant movement but a series of individual, bold explorations by poets and authors alike.

The resilient energy of this literary period is best reflected in the words of the poet Charles Tomlison. “Anyone attempting to write on poetry today must inevitably feel the shifting of the ground under his feet: tomorrow is already here, and the arrival of a new poet or the republication of a neglected one has altered the sense of priorities.”