Doni Tondo: A Visual Analysis of Michelangelo's Masterpiece

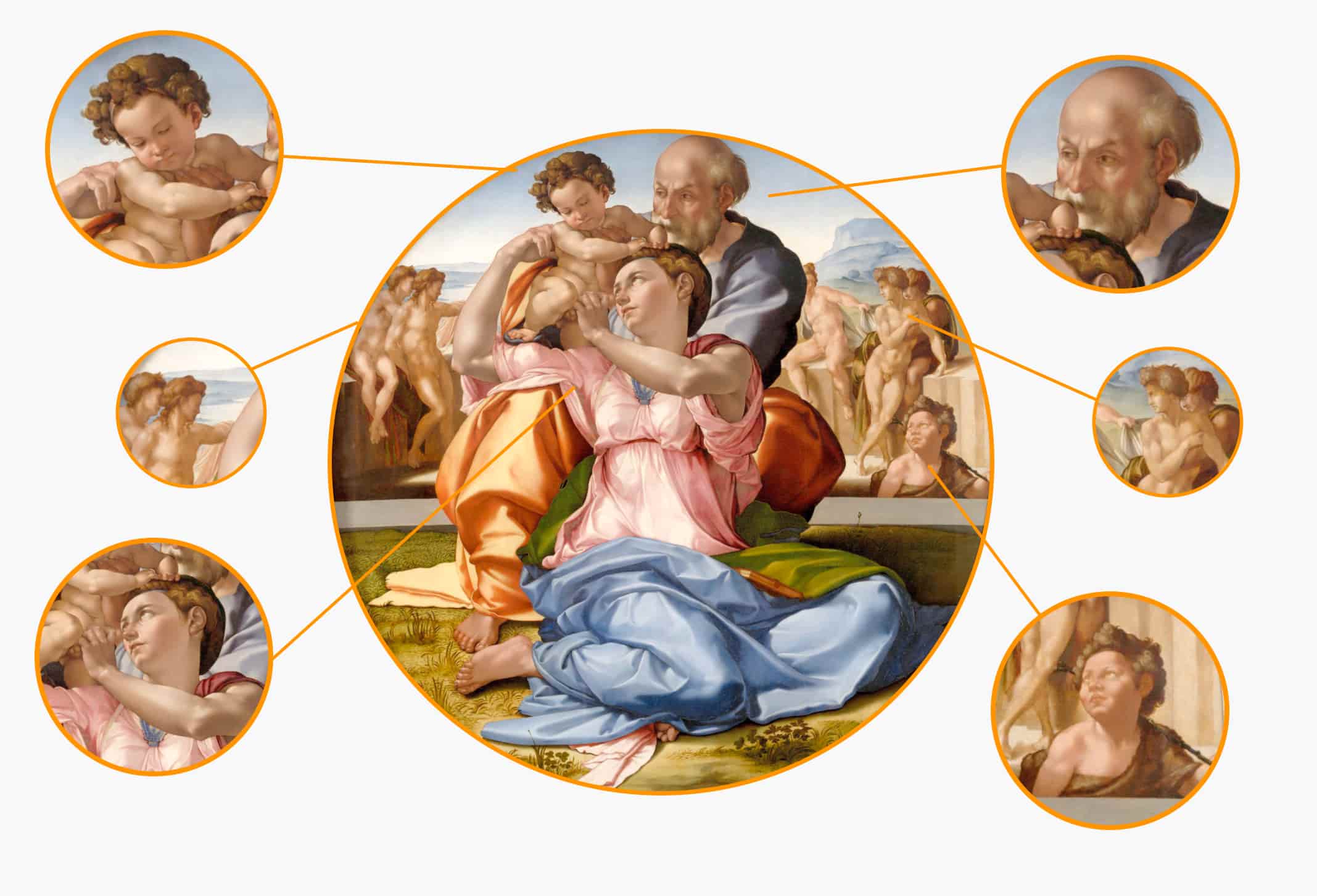

Located in the gallery of Uffizi, Michelangelo’s Doni Tondo (Tondo Doni) portrays the holy family and represents a unicum in Michelangelo's artistic production.

Doni Tondo, a renowned artwork by Michelangelo, has long been a source of inspiration for art enthusiasts and critics alike. But for me, this masterpiece holds a deeper significance, evoking a sense of personal validation and ego boost. Join me in exploring the depths of Michelangelo’s Doni Tondo as we analyse its style and history.

When was the Doni Tondo painted?

The Doni Tondo, a masterpiece created by Michelangelo Buonarroti, was painted between 1505 and 1507. Despite being a young artist at the time, Michelangelo had already achieved significant success with his earlier works, earning widespread praise from patrons and the public.

What was the significance of the Doni Tondo period in Michelangelo’s life?

During the period when the Doni Tondo was created, Michelangelo experienced a harmonious balance in his life, as his youthful energy and artistic success fuelled his growing confidence in his abilities and talent.

The Doni Tondo, a tempera painting, stands out as a singular piece in Michelangelo’s oeuvre, as it is the only work with definitive attribution to the artist that features a movable support.

What is the meaning of Tondo in art?

The term tondo is linked to the circular shape of both the work and the frame that encompasses it. The wooden surface of the frame enhances the beauty of the painting because it is conceptually connected to it. In fact, although it was made by the hands of Marco and Francesco del Tasso, it was executed according to a design by Michelangelo himself.

Who are the five figures on the Doni Tondo frame?

The Doni Tondo frame features intricate decorations, including intertwined plants, animals, and satyrs, as well as five small sculptures of heads that emerge from the base.

These heads symbolise Christ, prophets, and sibyls, and their positioning suggests that they are observing and emotionally engaging with the scene within the tondo. The painting itself portrays the Holy Family as the central focus, with a young Saint John the Baptist and additional captivating figures in the background.

What was the purpose of Michelangelo’s Doni Tondo?

Michelangelo’s Doni Tondo, featuring the Holy Family, reflects a common theme in the historical and artistic context of the time. Religious and civil virtues were the predominant subjects in artwork during this period. However, Michelangelo’s interpretation of this theme is uniquely original, offering fresh insights and philosophical perspectives that set it apart from other similar paintings.

Painting ennobled by the conceptuality of sculpture

A key observation of the Doni Tondo reveals Michelangelo’s belief about painting – that subjects should be created using the same preparatory criteria and meticulous attention to detail, particularly anatomical, as in sculpture. In essence, painting should be “ennobled” by incorporating the conceptuality of sculpture to achieve the perfection of the art of sculpting.

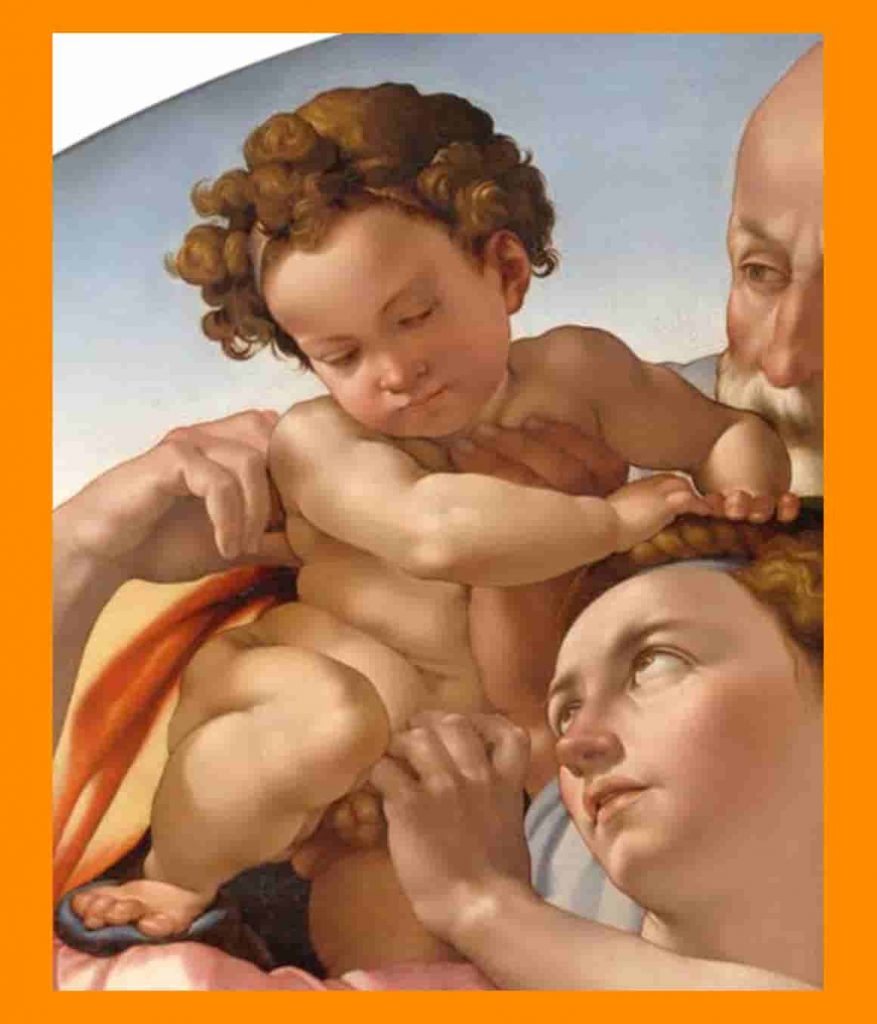

This concept is evident in the central group of the Doni Tondo, where the precise twist of Mary’s body in the foreground conveys tension and movement characteristic of Michelangelo’s sculptures. Joseph, holding Jesus on his lap, completes the harmonious composition.

Michelangelo’s emphasis on strength and muscular tension, typically seen in his sculptures, is achieved not only through the detailed anatomical drawing but also through the skilful use of chiaroscuro.

Lighting in Doni Tondo

In the Doni Tondo, the subjects are illuminated by a light source originating from the left, spreading across the painting’s surface and highlighting the figures and drapery with varying intensities. This distribution and angle of light result in unique vibrancy and depth in the colours of the garments, which Michelangelo carefully crafted through a harmonious chromatic balance.

Light serves as the key element that not only allowed Michelangelo to achieve unexpected colour shades but also enabled him to skilfully present the individual elements in an impeccable perspective.

What makes Michelangelo’s Doni Tondo a memorable masterpiece?

The Doni Tondo stands out as a memorable work from its historical period for several reasons. While the refined beauty of its drawing is certainly captivating, there is more to the painting than meets the eye. Michelangelo, a prominent figure of the Renaissance, demonstrates a thirst for infinity and a focus on the centrality of being.

His pursuit of beauty and essence, reminiscent of the classical period, is evident in every carefully considered and executed gesture. Michelangelo’s art communicates more than just the appearance of individual subjects; it conveys the knowledge and stories connected to them.

See also: The Perfected Thought by Michelangelo Buonarroti

Michelangelo’s work represents the fusion of art and culture at its finest. Examining each of his pieces is akin to exploring theology, philosophy, and the anatomy of the time, with the constant sense that the artwork is not only the pinnacle of artistic expression but also the culmination of a narrative that finds fulfilment and realisation within it.

Thus, the Holy Family in the Doni Tondo is more than just an idealistic and idealised representation of a family. It symbolises the culmination of humanity’s expectations, interpreted through the Christian perspective that influenced Michelangelo’s artistic vision.

Who are the figures in the Doni Tondo scene?

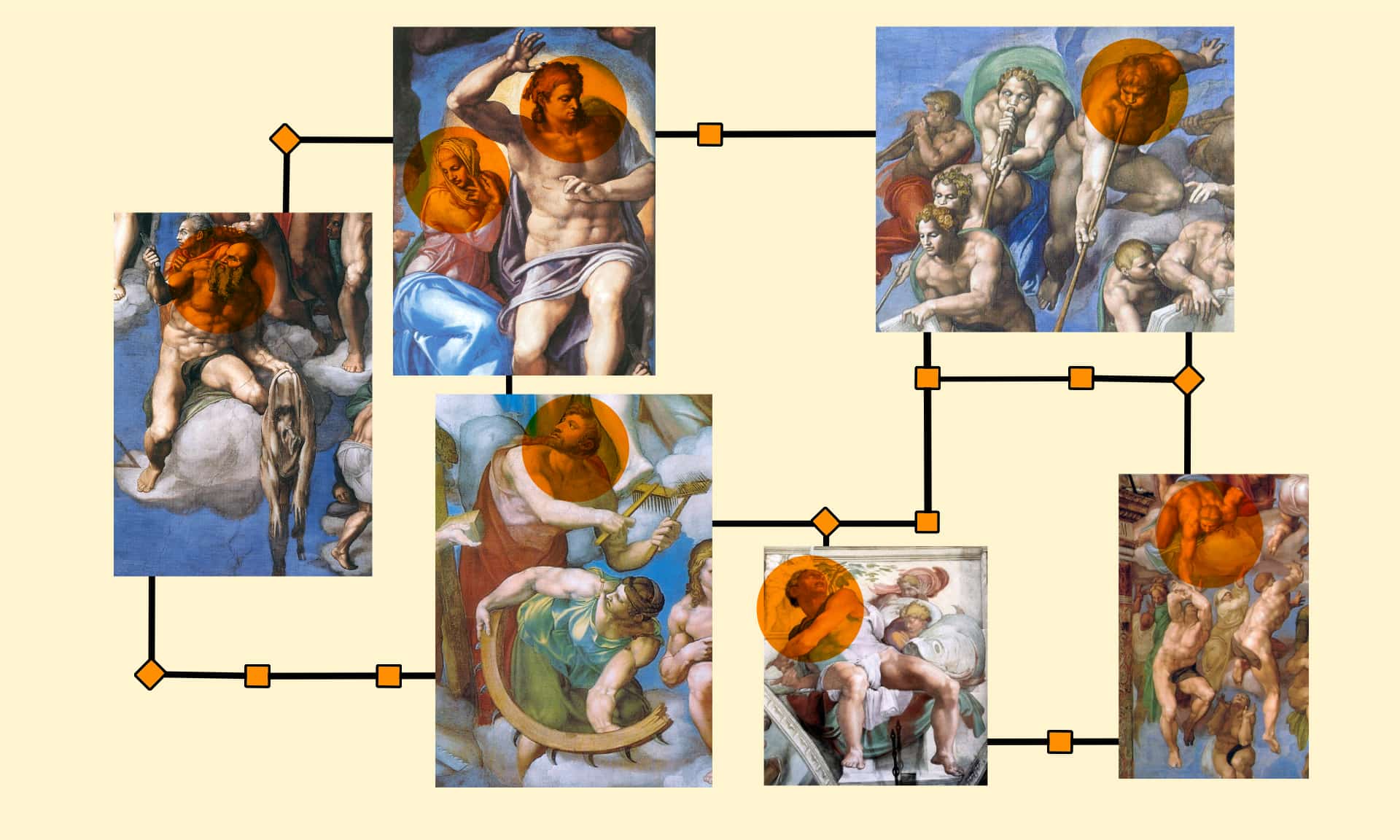

Doni Tondo by Michelangelo

The nude figures in Doni Tondo’s background symbolise humanity before Christ’s birth, representing people not, yet part of the salvation destined for humanity after Jesus’ arrival. These subjects are depicted naked, but their nakedness is not deformed by sin like the damned souls in the Last Judgment. Instead, it reflects their lack of the salvation message inherent in Christian thinking, much like Adam’s self-awareness in his naked state.

These figures may represent cultured and enlightened individuals influenced by ancient philosophy, but their nakedness signifies the limitations of classical philosophical thought alone.

To the right, St. John the Baptist contemplates the Holy Family. His presence is more than just a decorative element for balancing the overall composition; it symbolises the end of messianic expectation and the fulfilment of the divine promise. As the last of the prophets and the only one to witness the ancient promise’s fulfilment, St. John plays a crucial role in Michelangelo’s Doni Tondo.

Intriguing characters placed behind Saint John the Baptist

Absolute perfection is undoubtedly achieved in Doni Tondo’s central group, where the beauty of the depicted bodies contrasts with the nude figures behind them. This distinction lies in the dignity and awareness of the central figures, symbolising the fulfilment of an expectation through each chosen pose and, notably, the closed book on Mary’s lap.

Baby Jesus in Doni Tondo

While some interpret the closed book as a text announcing Jesus’ Passion to Mary, it can also be seen as a symbol of the end of a waiting period, marked by the acceptance of Joseph and Mary, the scene’s protagonists, along with their child.

The chromatic choice in the central group serves not only as a stylistic device but also as a means to emphasise the scene’s conceptual construction.

The study of Doni Tondo encompasses not just philosophical and conceptual aspects but also practical elements, enabling a deeper appreciation of the work’s small details. Both the choice of subjects and the shape of the tondo demonstrate an artist’s response to the specific needs of a commissioned piece.

Who is commissioned Michelangelo Doni Tondo?

Agnolo Doni commissioned Michelangelo’s Doni Tondo as a gift for his wife, Maddalena Strozzi, whom he married in 1504. The painting’s creation was likely prompted by either their marriage or the birth and baptism of their firstborn, Mary, in 1507. The Baptist’s presence in the painting supports the latter possibility. Both significant dates align with the chosen subject and the form of the piece.

Understanding the context in which a work of art was created is crucial for its accurate interpretation. Artistic creations are influenced not only by the specific artistic style of the time but also by the social reality and general culture in which they were conceived.

Agnolo Doni and Maddalena. Agnolo was the commissioner of Doni Tondo. Portraits by Raffaello Sanzio.

In a society as deeply rooted in religious thought as the Renaissance, it is fitting that the birth of a family would be celebrated by using the Holy Family as a reference model. Marriages during this period aimed to generate offspring who would ensure the continuity of one’s family line and, often, provide an adequate workforce. For noble marriages, like that of Agnolo and Maddalena, children also served as the element that sealed new alliances between affluent families.

Considering the significance of children during that time, we can now discuss the unique rounded shape of Doni Tondo. Although tondos were not entirely new in the artistic production of the period, this particular tondo stands out as a “desco da parto,” a round tray often painted on both sides and used by noble families to serve food to women who had recently given birth.

Desco da parto was a significant symbolic gift to celebrate successful births in medieval Florence and Siena.

This defining element of the work supports both proposed dates by historians, as it signifies either a wish for prosperity if given during the wedding or a celebration of a happy event following tradition if given upon the birth of a child.

Regardless of the specific timing or reasons for its creation, the Doni Tondo would not have come into existence without this social custom. Its connection to tradition and the story it tells make it easy to remember the various elements of the painting, allowing for a deeper understanding and internalisation of the piece beyond sterile technical data.

Final Words

The essence of art appreciation lies in understanding and contextualising a piece, rather than simply memorising dates and technical data. A personal anecdote illustrates this point: during a Medieval Art History examination, the author was asked to recall the birth and death dates of Robert Guiscard, a condottiero rather than an artist. Despite having prepared diligently, the author was unable to provide the exact dates and failed the exam.

In the next attempt, the author approached the exam with a focus on memorising numbers and dates, but years later, none of these details were retained. In contrast, every single detail of subsequent art studies, including the Doni Tondo and other remarkable works, was remembered vividly because they were understood and contextualised.

The true value of art appreciation comes from immersing oneself in the story and context behind a work of art, enabling a deeper connection and understanding that goes beyond sterile facts and figures.