“Art for all”: Della Robbia and the glazed sculptures of the Renaissance

In the 15th century city of Florence, Luca della Robbia goes on to create a recipe for the perfect glazed sculpture, an art form that, at the time, did not fit into the rigid cataloging art.

We are living in a difficult historical moment, in which each of us, myself included, in a more or less “blatant” way, has had the need to talk about covid. In this article, however, I would like to describe how covid spoke to me. Fortunately, I have not experienced the disease, but I have certainly experienced all the restrictions associated with it in a conscious way. The silence and being at home awakened in me memories: images and situations from the past that everyday life had made me put aside. With a different and certainly more mature awareness, I was able to clearly define what is important to me.

In particular, I really understood who was fundamental for my personal growth. I am talking about all those people who have given me a most precious gift by sharing their experiences and culture, giving rise to curiosity and aspects of my character that I never even imagined to possess, such as these discourses about art.

Obviously, I cannot fail to name parents and siblings, but these fall within that unique sphere I have already mentioned, but I have identified many other people who have come into my life by chance, or as a consequence of my personal choices. I remember Father Francesco who inspired my curiosity to read, my middle school teacher who gave me the skill to use words and understand their value. I fly over the hazy period of high school where only rarely did I perceive a nurturing warmth, to get to all the fantastic gifts I received during my university experience in Perugia.

Every work of art hides…

Above all, I experienced the exceptional teachings (both in form and content) of two professors: Pasquale Tuscano, who revealed new aspects of Italian literature and Giancarlo Gentilini, who helped me discover the marvels of modern art. It is not an exaggeration to speak of discovery because, despite my previous humanistic training, no one before him had been able to open my eyes to the message that every work of art hides. Both professors took me further than I had thought possible, making me discover a fantastic world that up to that moment, at least for me, had remained unexplored.

It is precisely among the various masterpieces that I only really got to know thanks to Professor Gentilini, that I chose the topic of this article: the glazed sculpture in the Renaissance, which is one of the topics to which his research is most associated. Indeed, I drew information from his research for this article.

The genius of Luca della Robbia

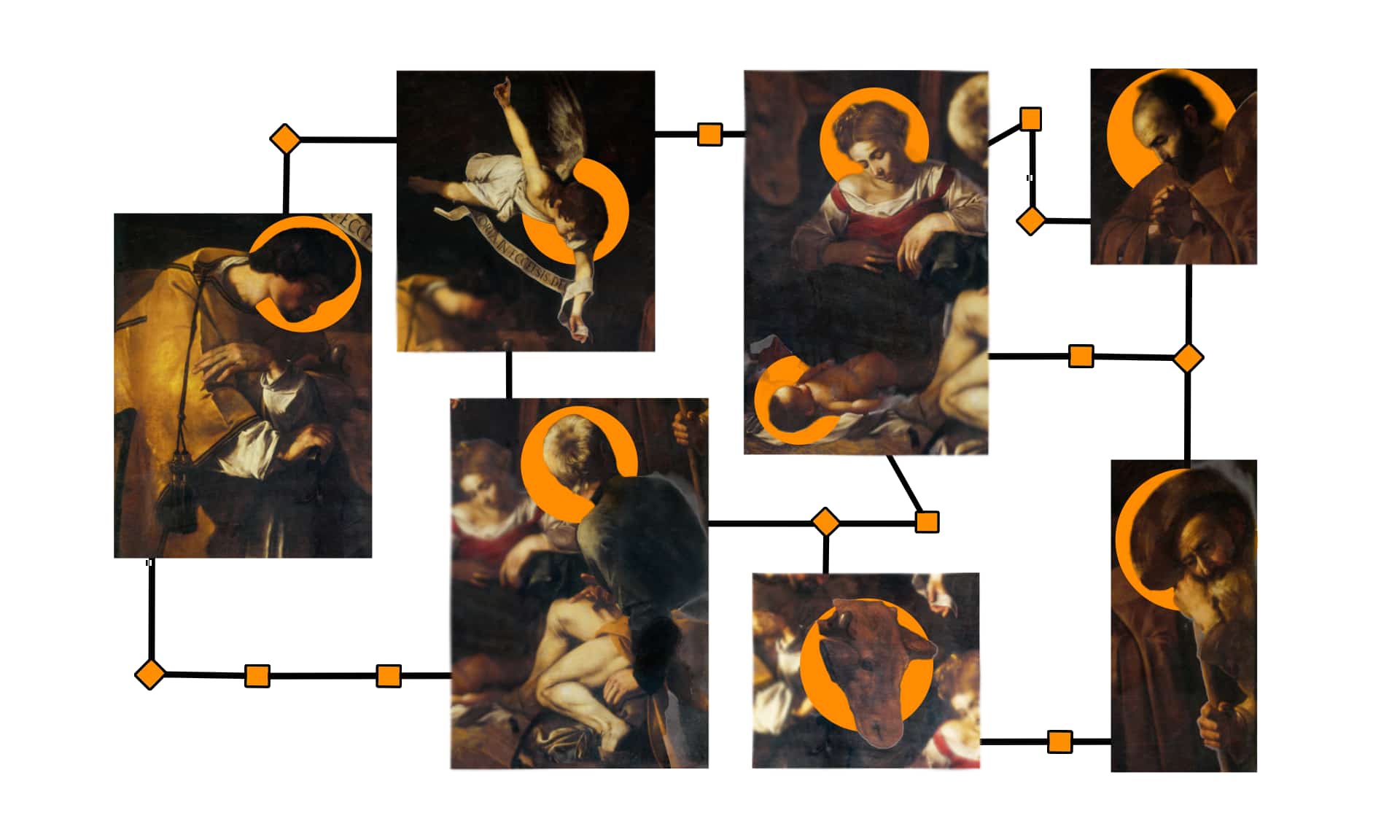

Luca della robbia, Nativity. Made around 1460

Taking the concept of art to the extreme, as many critics do, it could easily be said that art is basically divided into two major sectors.

There is the art of removing, namely sculpture; and the art of adding on, that is painting. In such a clear division, each artist should create works following the peculiarities of a single type of art, the one that they feel closest to. Therefore, from such a position, those who make sculpture should not paint and vice versa. In this rigid cataloging of art, it would be quite challenging to place glazed ceramics in the “right sector” because this, as we will see, represents a perfect fusion of the two ways of making art.

This type of technique immediately takes us to the city of Florence, where this art was born, thanks to the artistic intuition of Luca della Robbia (1400-1482).

The glazed terracotta and its “secret recipe”

In 1440, Luca reached the perfect balance between various elements to obtain his glazed terracotta. He then passed on the “recipe” of his works to the members of his family.

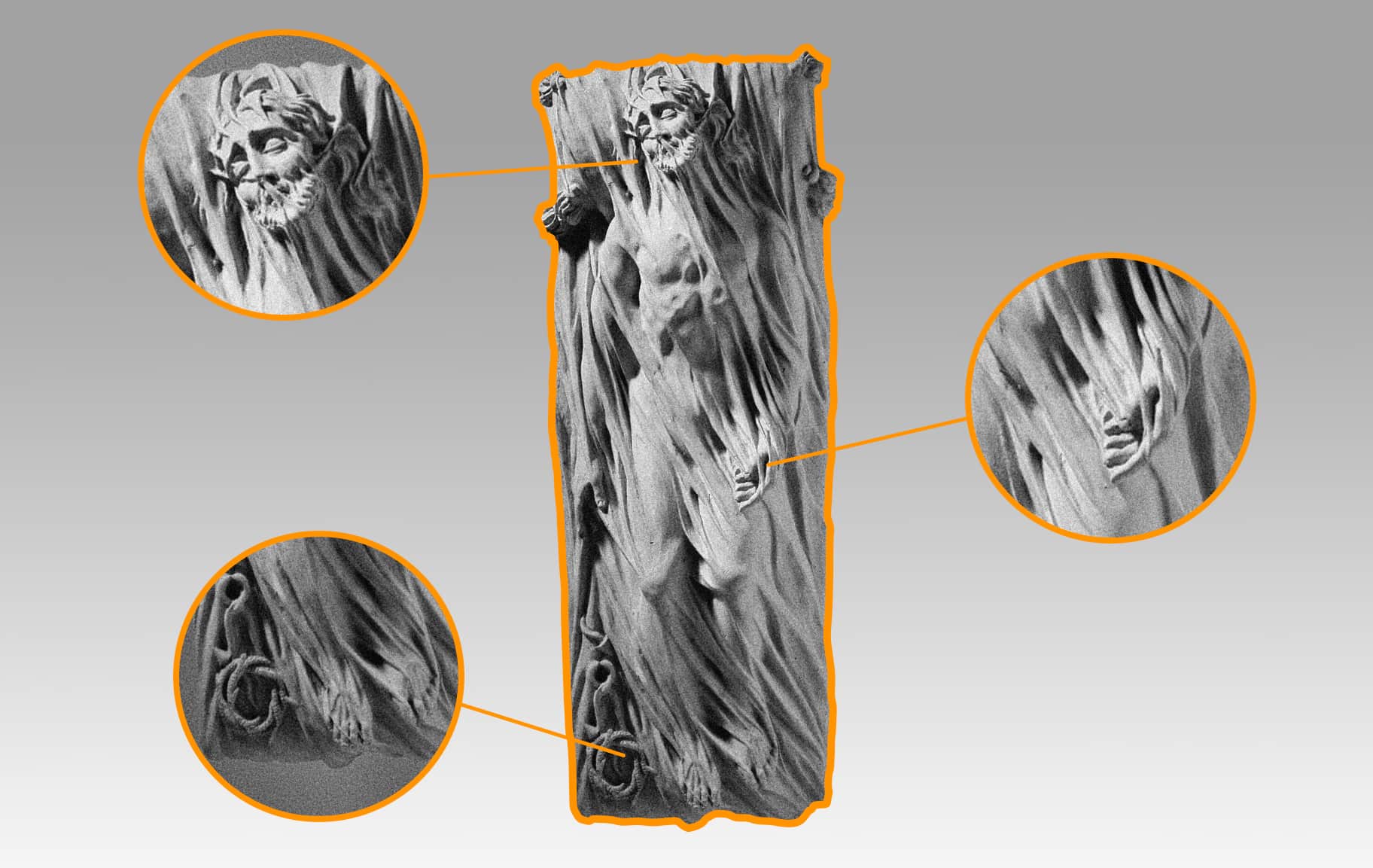

While in traditional sculpture the figure is obtained by subtracting layers of matter, in the case we are examining, the various works of art are obtained by adding elements. All this through a fusion of art and science, because the elements used for the sculptures are worked through a process that is not too far from that of fossilization. The material obtained by Luca della Robbia, through this process, has a consistency that guarantees resistance both to the passage of time and to the wear of atmospheric elements. This resistance is not only of the material itself, but also of the polychrome elements that are applied on it.

Recent scientific studies have been conducted by a group of researchers at the Louvre on various works carried out by Luca della Robbia and his family. The analysis with ion beams, mass spectrometry and fluorescence, have partially revealed the percentages of the elements used for obtain this terracotta, whose luster and vitreous effect, very similar to that of majolica, is obtained thanks to an enamel based on tin oxide, lead oxide and siliceous sands with an alkaline element. On the other hand, different metal oxides are used to obtain the different varieties of colors.

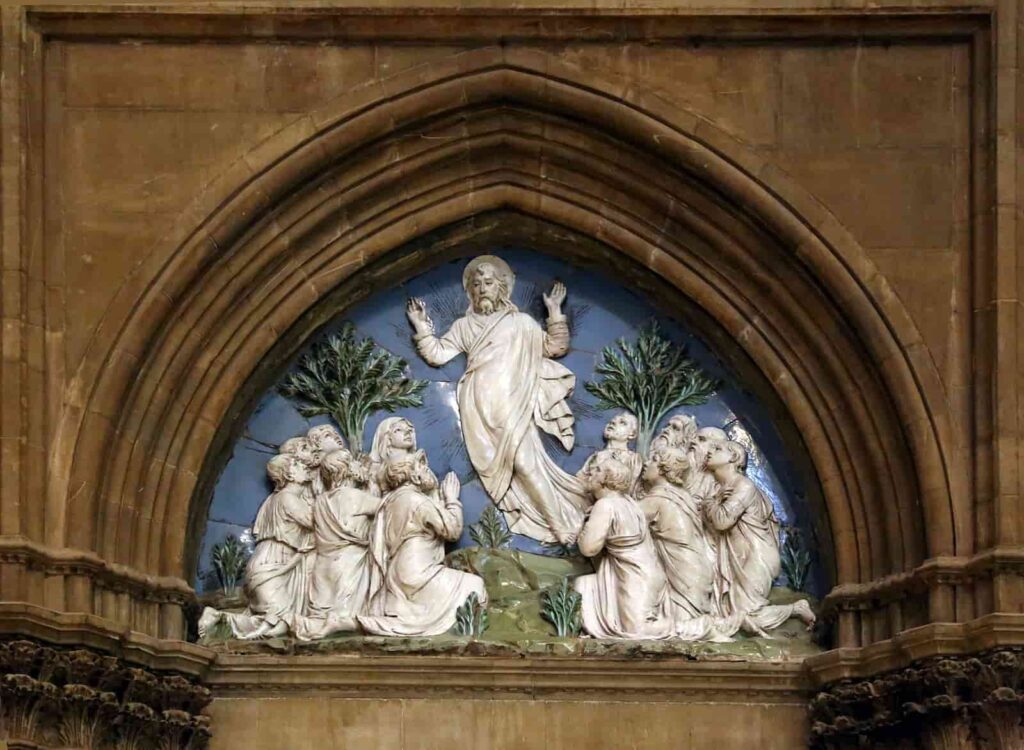

Many of Luca’s early works have very simple coloring, with the prevalence of blue and white tones. With time and the development of the technique, yellow, green (in the shade of turquoise), brown and black were added to the basic range of colors.

Santa Maria del Fiore (Florence) - Sagrestia dei Canonici

The glazed terracotta of the della Robbia, starting from the mid-15th century, met with enormous success, because the works created with this technique had such characteristics that they could be exhibited both outside to give luster to the buildings, and inside, where the brilliance of the surface made the characteristics of the exhibited work very evident, even when the lighting was poor.

Not only a brilliant, but also made for everybody

Many Renaissance works are rightly considered elite, not only for the genius of those who created them, but also for the social class of the clients who requested them by paying really significant sums to the artists concerned.

The works of the della Robbia, without detracting from the quality and beauty of the works they made, could almost be referred to as “popular”, because they were really within everyone’s reach. In fact, by studying the documents of the time that have come down to us, we can see that the clientele that first turned to Luca and then to his family members, was really wide, ranging from the upper middle class to the clergy, from brotherhoods to the popular classes. This is because once the technique was perfected, the della Robbia created molds that were able to easily reproduce works that were most in demand.

The numerous tabernacles reproducing the Virgin and Child, which responded precisely to the needs of popular devotion, are an obvious example of this large production. With such a large audience, the della Robbia obviously did not only perform religious works, but also family or corporation coats of arms, and other subjects suited to the life of the courts. Thanks to Luca’s nephews Girolamo and Luca della Robbia the Younger, who worked in the French court of Francis I, glazed terracotta spread beyond regional and national limits.

The best known Renaissance works, the most studied ones, as I mentioned earlier, have characteristics that certainly make them materially and conceptually unrepeatable. Conversely, the art of the della Robbia can be characterised by a uniqueness of thought rather than an exclusivity of diffusion. Suffice it to say that more than four thousand works were made in their family’s workshop.

In addition to having created a new and revolutionary material, I believe that the della Robbia family had above all the special merit of having given dignity to this technique, because before them the terracotta sculptures were made only as sketches for sculptural works. Above all, I believe they have given dignity to the users of this new form of art, thanks to which everyone could finally afford to touch the beauty with their own hands.