David Herbert Lawrence: The Freudian who hated industrialisation

David Herbert Lawrence has captivated the imagination with his rich and substantial prose, painting a clear picture of reality with spontaneous language.

Early Life

David Herbert Lawrence was born on the 11th September 1885 at Eastwood, a poor small mining town near Nottingham. He was the fourth of five children. His father was an uneducated collier who was fond of drinking and having a good time. His mother, on the contrary, was a well-educated retired teacher whose determination and puritanical strength of character greatly influenced her son’s psyche. The social difference between D.H. Lawrence’s parents was the major cause of the endless quarrels and rows that used to take place in the Lawrence family.

At the age of thirteen, Lawrence applied for a scholarship to Nottingham High School and managed to win a 12 pound per annum grant. This meant that he could receive a secondary education which was quite unusual for a working-class boy at the end of the 19th century. By the age of 16 he was already working as a clerk with a firm that produced surgical goods. However, his life was to suffer its first major blow which was to change the course of his existence.

The cover of Sons and Mothers by David Lawrence.

Lawrence, who had always been a sickly child, fell seriously ill with pneumonia. Lydia Lawrence, his mother, dedicated her heart and soul to her son’s physical well-being and felt that she was going to lose him. This created an almost morbid attachment which was to emerge so vividly in one of D.H. Lawrence’s most famous novels, Sons and Lovers.

When Lawrence was on the mend, he began his visits to the Haggs, a farm which was managed by the Chambers family. These were the happiest years of his adolescence. The Chambers took to Lawrence immediately and enjoyed his company a great deal. Lawrence was to say later: “a new life began in me there”. One of the seven children of the Chambers, Jessie, was to play a very important role in Lawrence’s life. Her soft poetic nature mixed with an acute intelligence mesmerised him totally.

Together they read poetry and talked of nature and love. It was Jessie who recognized his creative talents and encouraged him to become an author. The two were engaged for some time. However, Lawrence’s jealous and domineering mother made life hell for them. They eventually broke up, but Lawrence immortalised Jessie in his novel Sons and Lovers in which Miriam was in fact a transference of Jessie herself.

Lawrence then went to Nottingham University College from where he obtained a teacher’s certificate. In 1908 he accepted his first post as a teacher at Davidson Road School in Croydon. His mother died 1910, but the scars that her possessive love had left on Lawrence were to remain forever. The following year he wrote his first novel, The White Peacock, and the year after, in 1912, he left Croydon and wrote The Trespasser, a novel on the experiences which he had had there.

In March of that year Lawrence met the person who was to become his lifelong partner, the German wife of his former Professor of French, Ernest Weekley. Her name was Frieda Von Richtofen and she already had three children of her own. Two months after their meeting they eloped to Germany and after her divorce they were married in 1914. The two were an unlikely couple. Frieda had a very strong character and was even five years older than Lawrence. She reacted fiercely to his erratic and domineering nature, and this combination, although sparking off violent scenes and endless quarrels, worked well for both of them. The couple eventually settled in the south of England.

David Herbert Lawrence & Frieda von Richthofen were married in 1914 and settled in south of England. Colorised photo: Photo by the UN-aligned design team.

After World War One broke out, Lawrence had to face two serious problems. The first was the hostility towards him by the British authorities, who were aware of his anti-war position and who regarded his wife, a German, with great suspicion. At one stage Lawrence was actually suspected of being a spy for Germany. Their passports were confiscated and life at Zennor, in Cornwall, where they had settled, became unbearable. The second problem for Lawrence was the British censorship, which labelled his work as obscene. The first novel which was the target of the Public Morality Council was The Rainbow, published in September 1915.

After the war the Lawrences could finally travel again. On the restitution of their passports, they left England for good and by March 1920 they settled in Taormina, in Sicily, where they remained for two years. Being totally fed up with Europe they then travelled the world, visiting Ceylon, Australia, America and Mexico.

They then settled in New Mexico where they had been invited to go by Mabel Dodge Sterne, a rich American eccentric who was married to her fourth husband, an American Indian called Tony Luhan. In Taos, New Mexico, Mabel had founded an artists’ colony and had hoped to entice Lawrence to become part of her eccentric dream. The experience lasted only until 1925, when Lawrence decided to return to Europe. At first, he settled in Italy and then in the south of France, where he died of tuberculosis on the 2nd of March 1930.

The restless and adventurous life of D.H. Lawrence has captivated the imagination of many artists and writers. A successful feature film called The Priest of Love, based on his life, was released in 1981. The film, which was taken from The Priest of Love by Harry T. Moore, was based on Lawrence’s letters and writings.

Literary Career

The cover of The White Peacock which was Lawrence’s first novel.

D.H. Lawrence started writing his first novels when he was still in his early twenties at Croydon. In 1911 he released The White Peacock which was his very first publication, and in the following year The Trespasser. The former novel, published by Heinemann, foreshadowed Lawrence’s interest in the intricate relationships between men and women, while the latter portrayed his life in Croydon.

Lawrence had also been working on an autobiographical novel which he entitled Paul Morel. This novel was eventually published in 1913 as Sons and Lovers and is one of his most well-known books. Jessie Chambers, who had read the manuscript before its publication, noted that “Lawrence possessed the miraculous power of translating the raw material of life into magnificent form”. The novel reflected his own experience with his mother, her stifling love which verged on obsession and his own subsequent psychological development.

Lawrence returned to the man-woman relationship and sexuality in The Rainbow, published in 1915. Between 1915 and 1920 Lawrence wrote some significant poetry like Amores (1916), Look! We have Come Through (1917), New Poems (1918) and Bay (1919). 1920 saw the publication of the novel Women in Love which was a basic variation on the theme of the man-woman relationship. In the same year he published The Lost Girl and the play Touch and Go.

In 1922 Lawrence published the novel Aaron’s Rod, a collection of short stories, England, My England, and another of poetry, Tortoises. In 1923 he released another autobiographical novel based on his links with Australia and his relationship with the war, entitled Kangaroo. In 1925 he published another collection of short stories, St. Mawr & The Princess. He also wrote an account of his adventures in Mexico, focusing on Mexican primitive values, in the novel The Plumed Serpent.

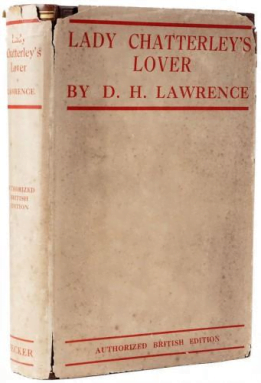

Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover was banned as obscene only to be released in its full edition in 1960, over 30 years after its publication.

In 1928 Lawrence saw the publication and subsequent confiscation of his most notorious novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover. The novel explored the psychology of sexuality and of social standing and it attacked industrialism in general. The story revolved around Lady Chatterley who was happily married to a handsome, upper-class lord. Tragically, due to a war injury, he became totally impotent. He obviously still loved his wife and she loved him. They lived on happily together, but their sexless relationship developed into frustration. Her need for sexual satisfaction was finally appeased when she commenced a relationship with the low-class gamekeeper who, although uncouth and unrefined, made Lady Chatterley feel her womanhood and her sexuality. The Freudian implications and the deep psychoanalytical study of sexuality was unfortunately not appreciated by British society. The book was banned as obscene only to be released in its full edition in 1960, over 30 years after its publication. Just before his death, in 1930, Lawrence wrote a very interesting essay on his notorious publication, A Propos of Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1930).

Style and Themes

Together with James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, D.H. Lawrence was the greatest innovative modernist writer. He, like Joyce and Woolf, broke away from Victorian tradition by creating a new approach through his novels. However, he differed from Joyce and Woolf because he focused on content rather than on style. He did not, for example, use the stream-of-consciousness technique, nor did he juggle around with punctuation and grammar.

His prose was rich and substantial, painting a clear picture of reality with spontaneous language. He emphasised the content which, for him, became more important than style. His writing was, however, veiled by a poetic aura which echoed the Romantics and the Pre-Raphaelites. The love of nature and naturalness was effectively expressed both in his prose and poetry through a simple and direct language. He eventually chose to write poetry in free verse to underline his belief that even language should be instinctive and not created logically.

The Supremacy of instinct over cerebral consciousness

A typical feature of Lawrence is his hatred for industrialisation which had removed the population from the natural beauty of the countryside to the squalor of the town. The slow metamorphosis of rural England into the cold industrialisation of the urban environment is vividly portrayed in both his major works. Sons and Lovers and Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

A very important characteristic of D.H. Lawrence is his belief in the Supremacy of instinct over cerebral consciousness. He honestly believed that the puritan heritage of England was the cause of most of the evils of his society; a society in which humans were forced to reject their natural instincts to follow an alien, bigoted logic. His ideas were closely associated with Freudian theories of sexual instincts and subconscious motivations. Lawrence believed that people could only be really free by following their primordial instincts and by refusing all logical interpretations.

He summed this up in 1912 by writing: “My great religion is a belief in the blood, the flesh being wiser than the intellect. We can go wrong in our minds, but what the blood feels, and believes, and says, is always true.”