Like Rings in The Water: Dante’s impact on Michelangelo

The divine complexity of Dante's Commedia has not only produced sterile admiration but has been able to generate new art in all the shapes and forms. This piece looks at Dante's impact on the Michelangelo.

When a stone is thrown into the water, the greater the power of the blow, the greater the number of circles produced on the surface. The image of these circles that indicate the passage of the stone in the water, is the symbol that most represents the power of art. In fact, creating a work of art means launching a message whose strength, just like that of a stone, cannot be confined to falling silently into the consciousness of the recipients of the art itself; the impact must generate waves.

Dante’s lasting impact

The divine complexity of Dante’s ‘Commedia’, no doubt fits In this discourse of power and resonance. It has not only produced sterile admiration but, as only a great masterpiece can do, it has been able to generate new art in the spectrum of all the languages of art.

He has given us new words, daring constructive choices, new images and new solicitations in the souls of those who, although not knowing how to express themselves through the languages of art, still manage to imagine new and different worlds within themselves. The list of those who have continued to make Dante live through their works has many names and has increased over the centuries.

This is a testimony to how the work as well as the man can survive their natural and inevitable temporal limits thanks to the very essence of art that makes true beauty, and those who have been able to express it, eternal.

Dante’s impact on Michelangelo

Rodin, Botticelli, Dalì and many others in their images and sculptures have given shape to Dante’s hell, but I find that no one has understood and brought its essence to life better than Michelangelo Buonarroti. What the former expressed in words was translated into images by the other, in what comes across as affinity between two similar souls. Two hundred and ten years of historical distance are cancelled by a unique interpretative closeness, the result not so much of the assimilation of a teaching between teacher and pupil, but rather clear testimony of a dialogue between minds and similar souls. A profound similarity that certainly originates from common factors.

First of all, Dante and Michelangelo’s training environment, albeit with different historical and social nuances, is the same. The political vivacity of Dante’s Florence resonates in the cultural vivacity and the intellectual dynamism of Medici Florence. This observation offers a complex discourse regarding these sublime minds, all the more so when we consider another common element, namely the temperament of the two artists.

Despite the apparent differences, I find that the coherence of ideals and style, as well as the confidence in expressing one’s abilities and talents, has produced the same fruits, despite all external elements such as the alternation of luck. Both would never have reached the perfection that characterises them if they had not been faithful to their feelings, displaying an integrity that has never made them bend to the will of others. They put themselves at the service of powerful patrons, but never by selling themselves. This is what allowed Dante first, then Michelangelo, to express themselves with authenticity and truth, giving shape only to their own vision and their own intimate and personal thoughts.

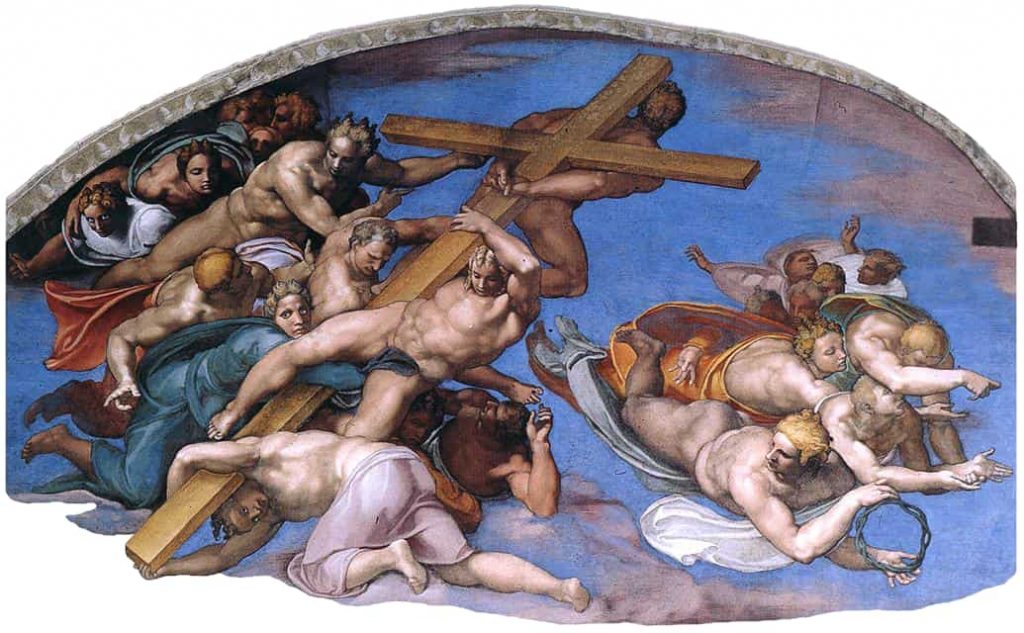

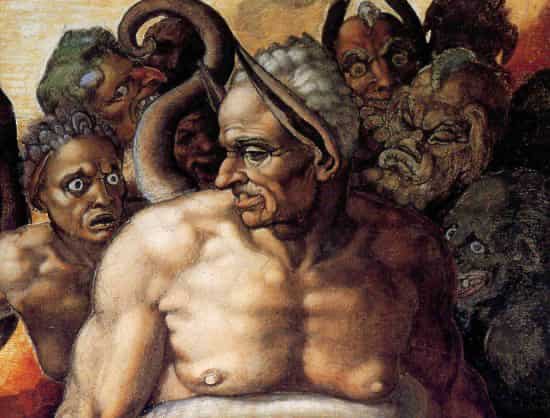

A scene from Michelangelo’s Last Judgment.

Another element that unites them does not come so much from the examination of their historical events, but from the stories they have told us. In fact, in both of their artistic productions they have done nothing but give shape to man in all of his facets. Man, understood as being aware of his most intimate nature and of all his actions. Man, whose beauty or poverty is exposed without filters, except those that the two have deliberately decided to put in order to facilitate their message for those who were able to grasp it. The cultural background of both was incredibly broad because it was free from self-imposed cultural limits. Nowadays culture is almost always limited to specific knowledge, purely curricular knowledge, aimed at building skills.

Dante and Michelangelo, on the other hand, have shown that they can move with fluidity and lightness through different fields of human knowledge such as ethics, philosophy, religion and anatomy.

Dante was able to play with words, giving them, through the use of rigid metric schemes, almost the same value and role of numbers in mathematical rules, without however making them prisoners of perfect form at the expense of substance. The same perfect form of Dante’s words is that of the characters in Michelangelo’s works where everybody, expression or pose does not stray from reality thanks to the artist’s careful study of painting techniques and human anatomy.

Just as Dante was able to describe the images with such intensity as to allow us to see them, so Michelangelo was able to translate his images, his drawings even, into words.

In fact, Buonarroti did not limit himself to expressing his feelings only through painting and sculpture, but also through the production of really interesting literary texts both in terms of form and content. This ability to express himself in different fields allowed Michelangelo to read Dante’s Divine Comedy with a deep awareness which, regardless of the considerations just made on closeness between the two, is certainly the element that most of all unites the two great artists.

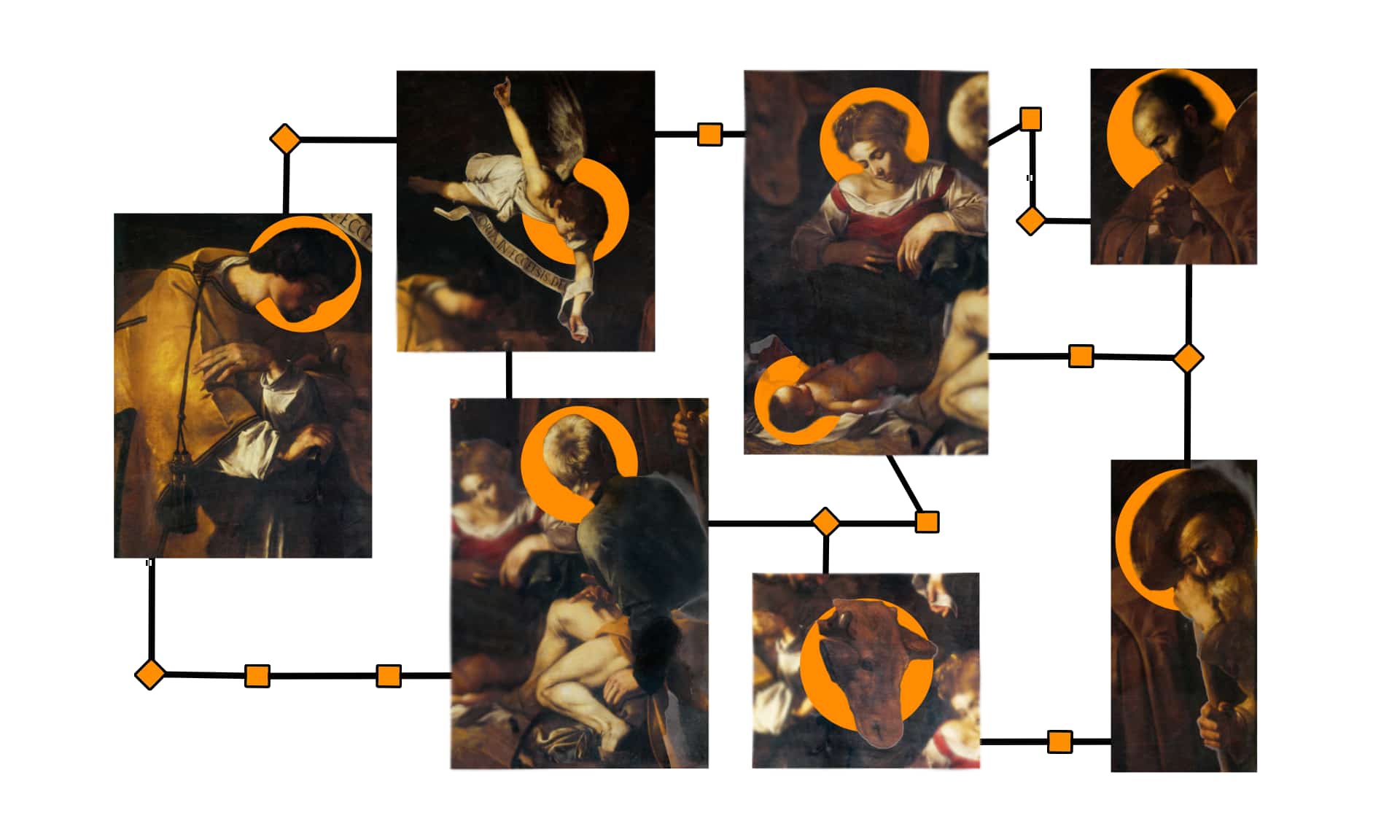

Within his Commedia’s afterlife, Dante had given “form” to the damned, their sin, and their thoughts, while Michelangelo, with the same deep and intimate feeling, gave colour and expression to the Last Judgement. You don’t need to be particularly expert in literature, much less in art, to identify Dantesque elements within the scene of Michelangelo’s Last Judgement: Minos and Charon in fact immediately and easily evoke the association between the two.

If this were the only element of association between the two works, the allusion would have simply been limited to a clever reference by Michelangelo. However, the element that really makes the feelings of the two artists similar, if not even equal, can be found in the reading of each of the detailed expressions of the saints, the blessed and the damned.

In the Divine Comedy, Dante describes people and characters, outlining their story through their guilt or bliss. In both cases he highlights the awareness that accompanies every single character who experiences every single moment of eternity, unlike living beings on earth.

Time and eternity

Michelangelo presents the same awareness, but he tells it to us at a given moment, that is, the one that unites present and finite time with eternity. The novelty, the uniqueness of this moment gives the expressions of the subjects depicted not only the same Dantesque expressive awareness, but also the feeling of amazement that accompanies every change. In the lower part of the fresco, in fact, the amazement of the bodies that wake up from the sleep of death is opposed to the awareness of those who have been living the afterlife for some time. Michelangelo’s fresco makes visible the pain of the damned and the beatitude of the blessed, with the same dynamic liveliness of the journey through Dante’s three otherworldly realms. As the poet, who while moving between the various circles escapes from dangerous demons, so in the fresco the bodies just awakened from the sleep of death elude the grasp of the devils who try to grab them.

Just as the souls of Dante give testimony and motivation of their otherworldly destiny, so the blessed souls of Michelangelo exhibit, almost as proof, the instruments of their martyrdom and therefore of their salvation.

A dig at one’s enemies

Minos was the son of Zeus and Europa. Every nine years, he made King Aegeus pick seven young boys and girls to be sent to be eaten by the Minotaur, a mythical creature who was part man and part bull.

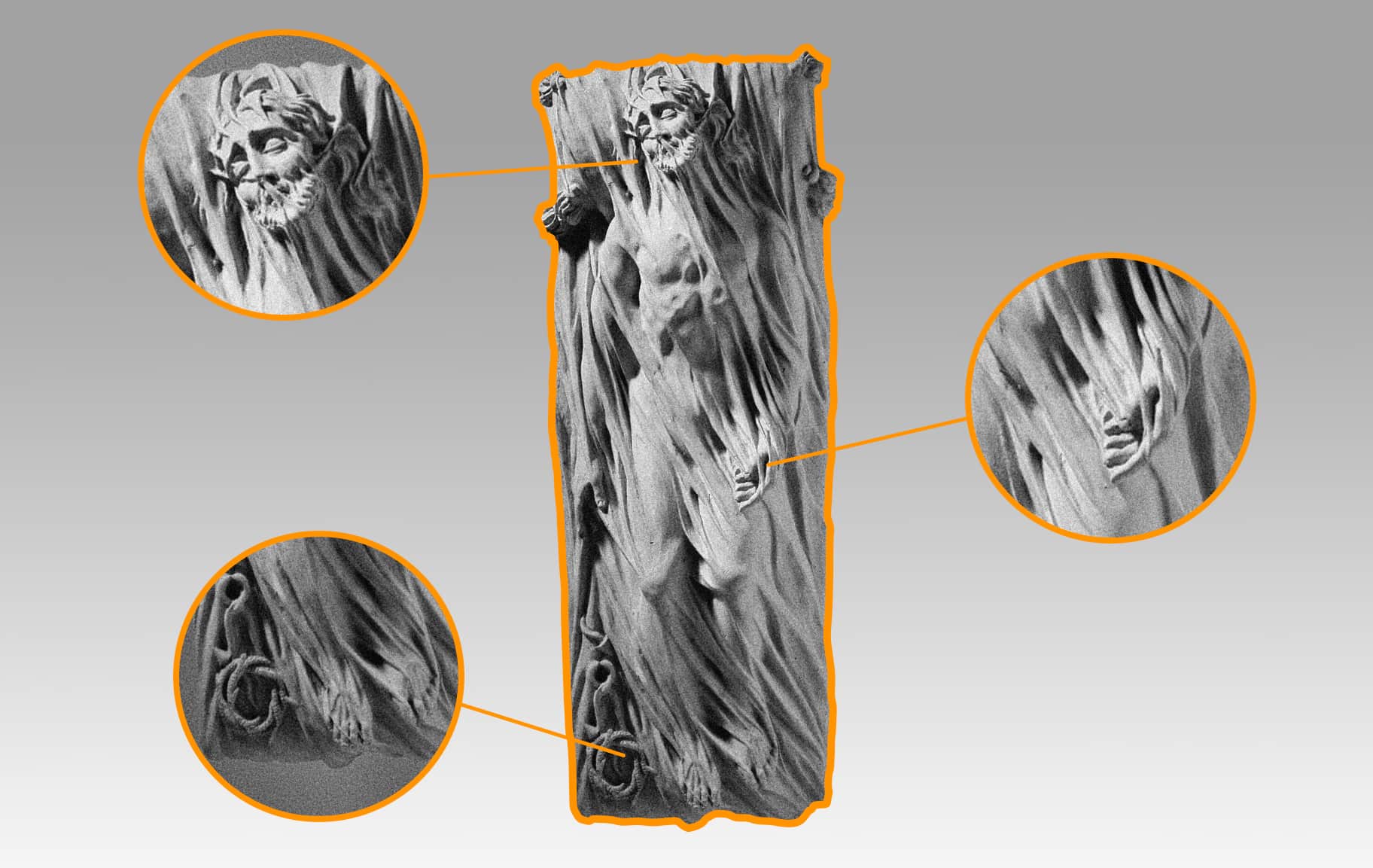

In this discourse of similarities and parallels, the figure of Minos has always struck me, particularly because it contains a strong conceptual link between the two artists. It is known how Dante, out of a spirit of justice and personal revenge, reserved for his political enemies, who were responsible for his condemnation and therefore for his exile, a place in the afterlife among the spirits of the damned. Michelangelo also acted following the same instinct, choosing Biagio Martinelli as a “model” for Minos. The papal Master of Ceremonies, better known as Biagio da Cesena, had been called to express himself about the fresco that Michelangelo was painting and chose to label the painter “dishonest” for depicting naked bodies inside a sacred place. As Vasari recounts, Michelangelo did not tolerate this comment, above all due to the dubious conduct of the Master of Ceremonies, whose habits were anything but religious.

Both Dante and Michelangelo had complex personalities and a great awareness of their own value, yet both represented themselves in their works on tiptoe. Dante presents himself as a mere spectator of the divine will, Michelangelo as a skin without a body in the face of the greatness of what was happening. The two artists wanted to celebrate their thoughts and their inspiration more than their personal glory. In so doing, they have given us messages that after centuries continue to vibrate in the souls of those who know how to welcome them.