Caravaggio and the unveiling of truth

Each of us is constantly torn between comfortable facade truths, and those deep and real truths that sometimes elude us. For most people, it is relatively easy to keep the uncomfortable aspects of authentic truths hidden. In the case of artists, on the other hand, especially the best known ones, this secrecy is lost because their lives, and their works, are often under the lens of historical and stylistic research.

Certainly, the interpretative freedom of many scholars often triggers serious historical debate, but regardless of the undeniable subjectivity of the judgments of others, the objectivity of many works is so evident that they certainly do not need the words or the judgement of the great critics to be read and understood.

The light from the chiaroscuro

I usually look at and speak only of the art that I like and, after having internalised it, I try to translate and interpret it in the way that I feel most personal, with the secret hope of being able to grasp at least a glimmer of the truth lived in the hearts of the artists that I love most. Sometimes this truth is difficult to interpret and comment on; at other times, however, I find myself talking about paintings that seem to me to contain truths without filters, without idealisations, which while obviously hiding precise messages, are almost completely devoid of the philosophical fabric typical of art of the past.

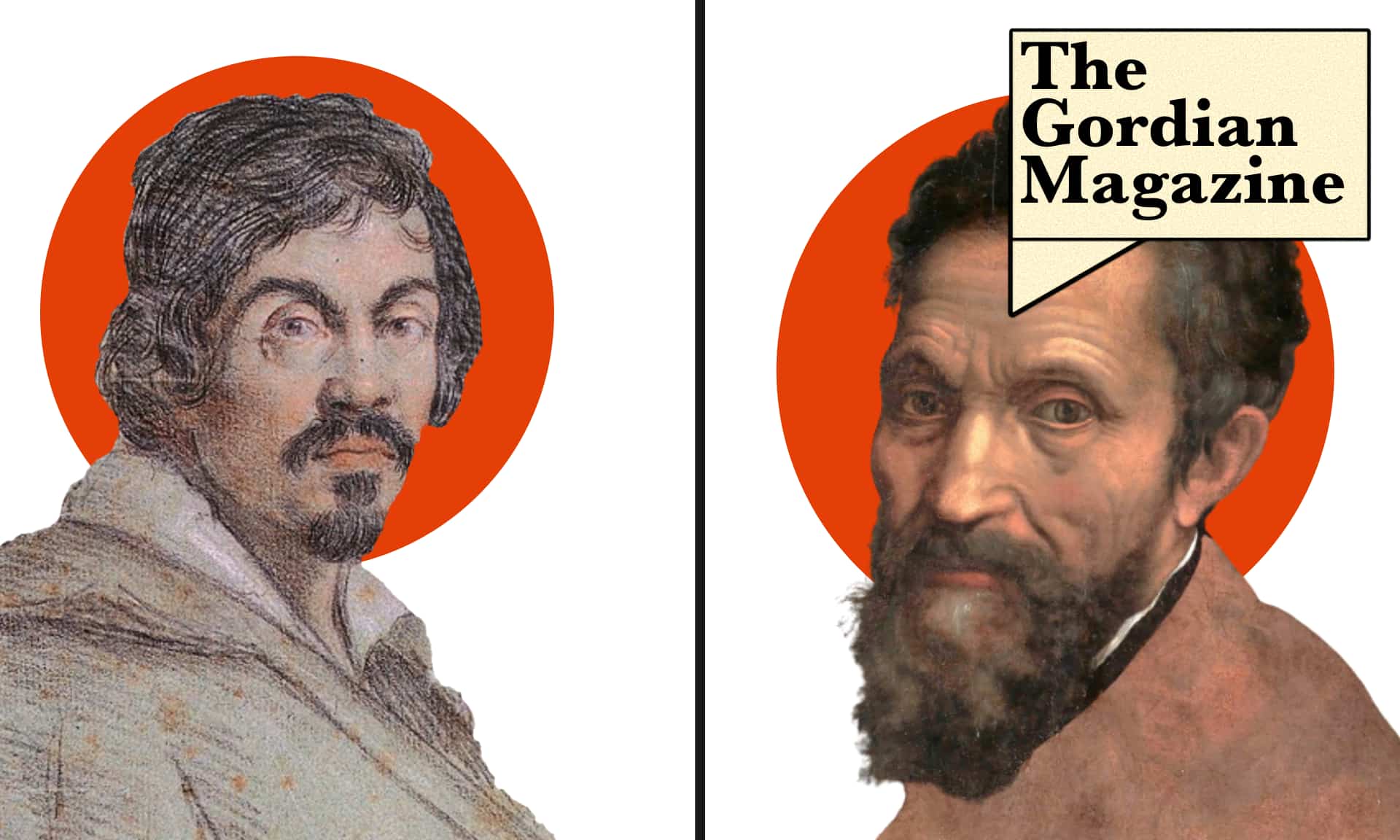

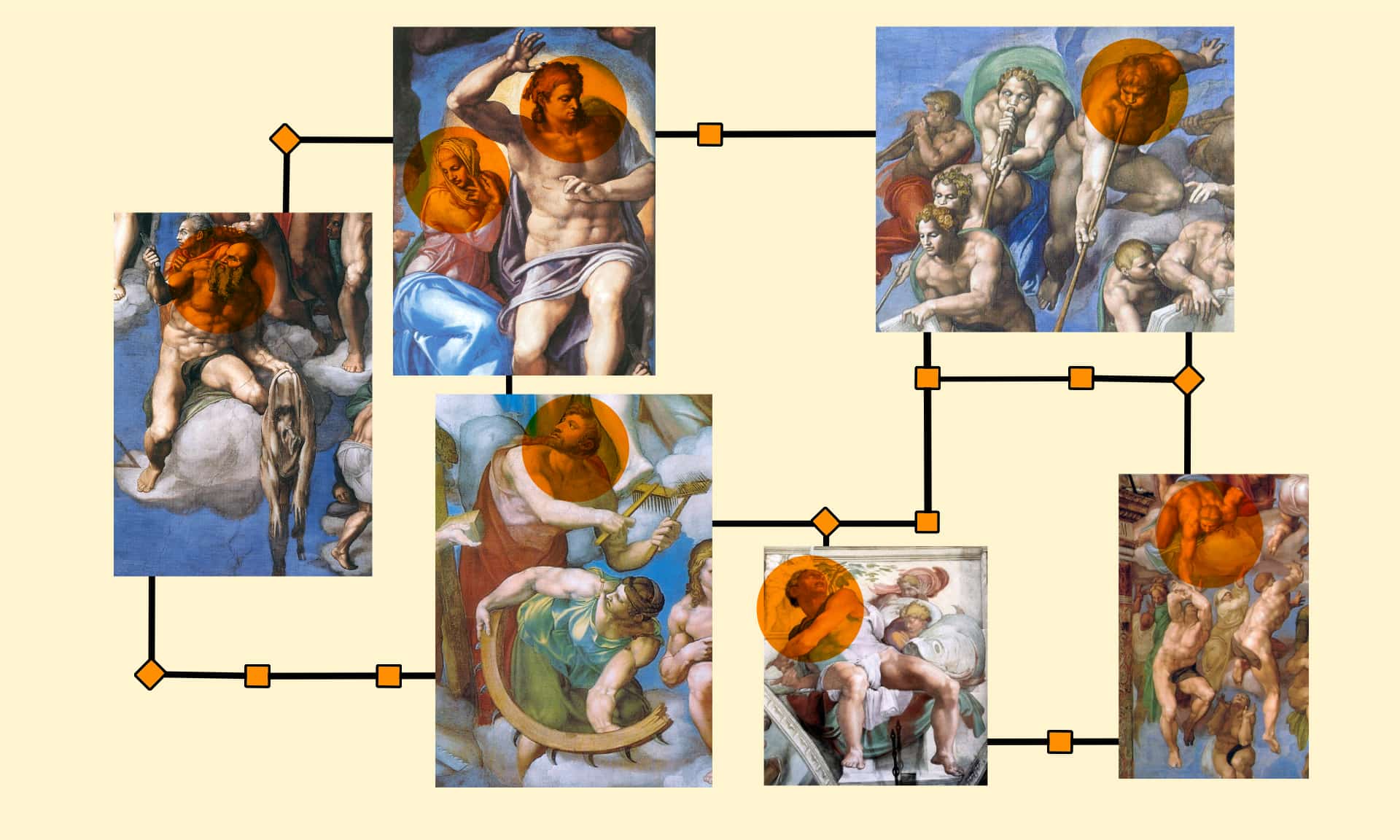

An example of this art, as beautiful as it is immediate, is undoubtedly offered by Michelangelo Merisi, better known as Caravaggio, who gave us clear and sharp images, almost as if they were snapshots of the moments narrated, even highly unlikely ones. His paintings can be perceived as a mirror of reality because they tell us the verisimilitude of the moment, even when this moment tells contexts and mysteries of the Christian faith, which were often depicted by other artists through the use of complex symbols that are difficult to decipher.

This same symbolism was so widespread that it was sometimes even present through the myths of antiquity, because these were often still interpreted from the perspective of the messianic message. The thematic and interpretative need linked to the sacred world was often determined by specific commission requirements of the work itself, which in many cases was so pressing as to lead the artists to a sort of self-censorship of their production, because a commissioned work could also be refused by the client if it did not correspond to the interpretative or taste needs of the time.

Reflecting a personal evolution

Free from these cultural and social constraints, which are sometimes even cryptic, Michelangelo Merisi in each of his works has told us stories through images capable of capturing the moment, with an immediacy that is sometimes so crude as to be almost offensive to his contemporaries.

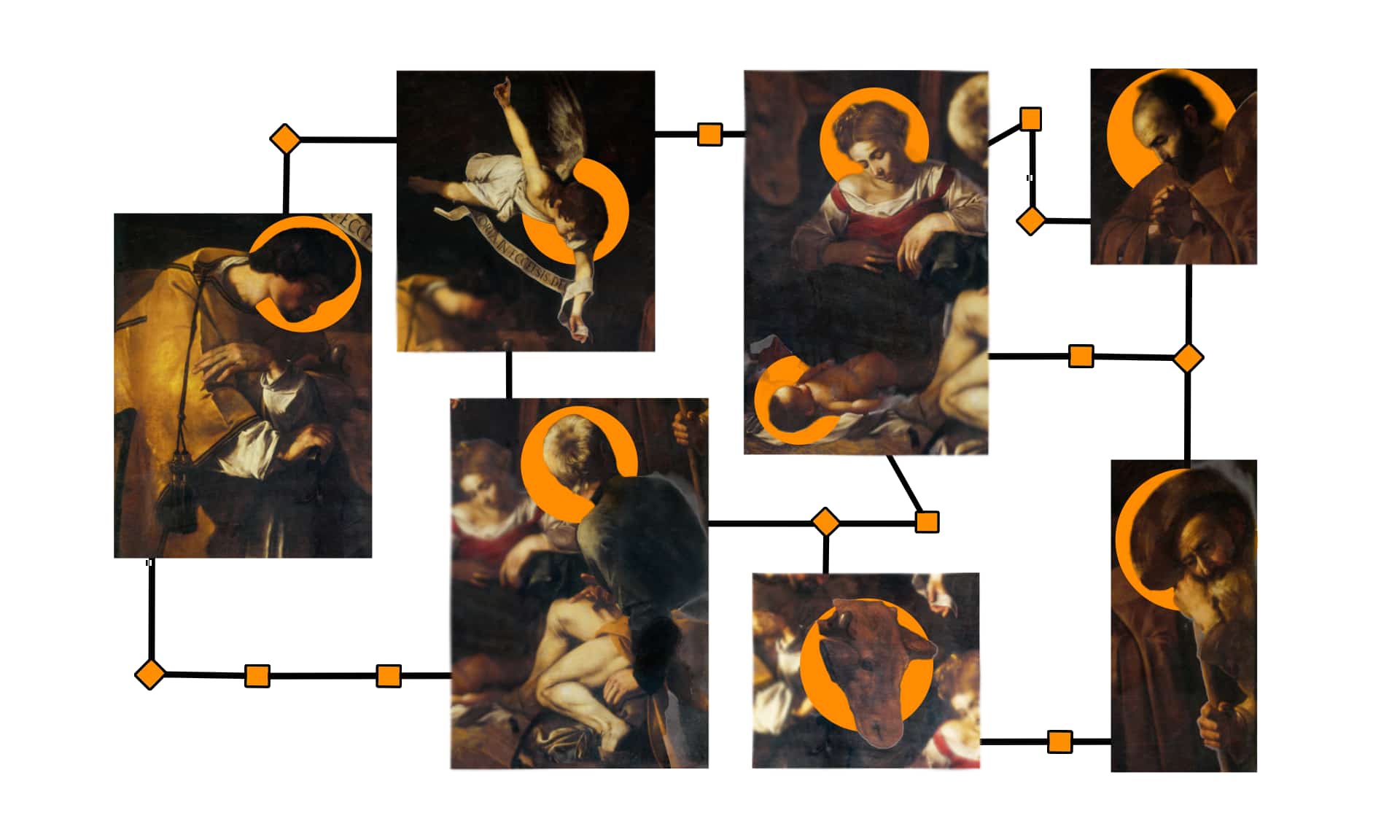

The comparison between Merisi’s works with others of the same period, allows us to understand how Caravaggio lived a completely personal and intimate stylistic evolution, free from pre-established schemes, or dependency on the inspiration of others.

After him, it is easy to come across painters who have made Merisi’s style their own. I am referring to the so-called Caravaggisti, but there are no artists imitated or “copied” by Caravaggio. The before and after that is captured in the style of his artistic production coincides with a before and after in the artist’s private life.

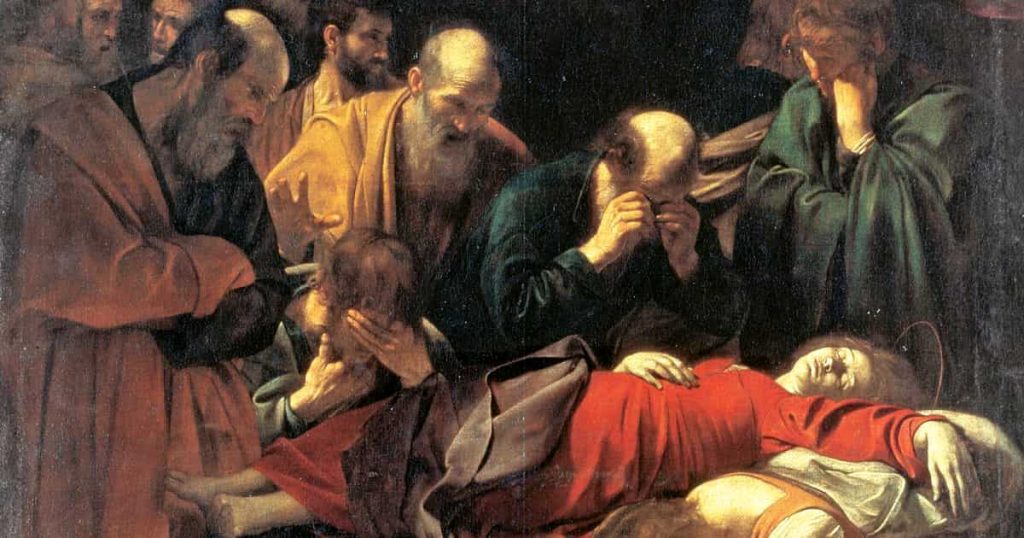

The personal event that acts as a watershed of this before and after was undoubtedly the murder, for trivial reasons, of Ranuccio Tommasoni in Rome in May 1606. In his art, this watershed is represented by the painting “Death of the Virgin”, made between 1604 and 1606, with stylistic and interpretative elements so far from the traditional iconographic tradition that they horrified both the client and the public at large.

The death of Virgin Mary by Caravaggio. On 29 May 1606, the great Italian Baroque painter Caravaggio killed Ranuccio Tommasoni in Rome. © Public domain

While the artistic changes could be read as a personal and conscious evolution of the painter to make himself a loyal interpreter of the truth, the historical information on Caravaggio transmit a much more complex picture characterised by emotional turmoil. This was most likely due to the effects of Merisi’s prolonged contact with toxic substances contained in the pigments used at the time, which led him to no longer control the most violent and extreme instincts of his character. The consequences of these breakdowns that took place in different areas over time, began to close in on him.

As a penalty for the murder of Ranuccio, Caravaggio was sentenced to immediate beheading by anyone who recognized him on the street. This led the painter to escape from Rome, starting a long pilgrimage that ended only with his death. The sentence, in fact, was never carried out by anyone, but at least symbolically it was carried out by Caravaggio himself. In fact, from the moment he was convicted, he began to obsessively paint severed heads, which most of the time depicted a self-portrait of the painter himself.

The thematic choices that characterised the works created during this period were not the only consequence of this change of life. In fact, the most significant consequence was the greater diffusion of his work, which without this condemnation would almost certainly have remained connected to a single court or town reality.

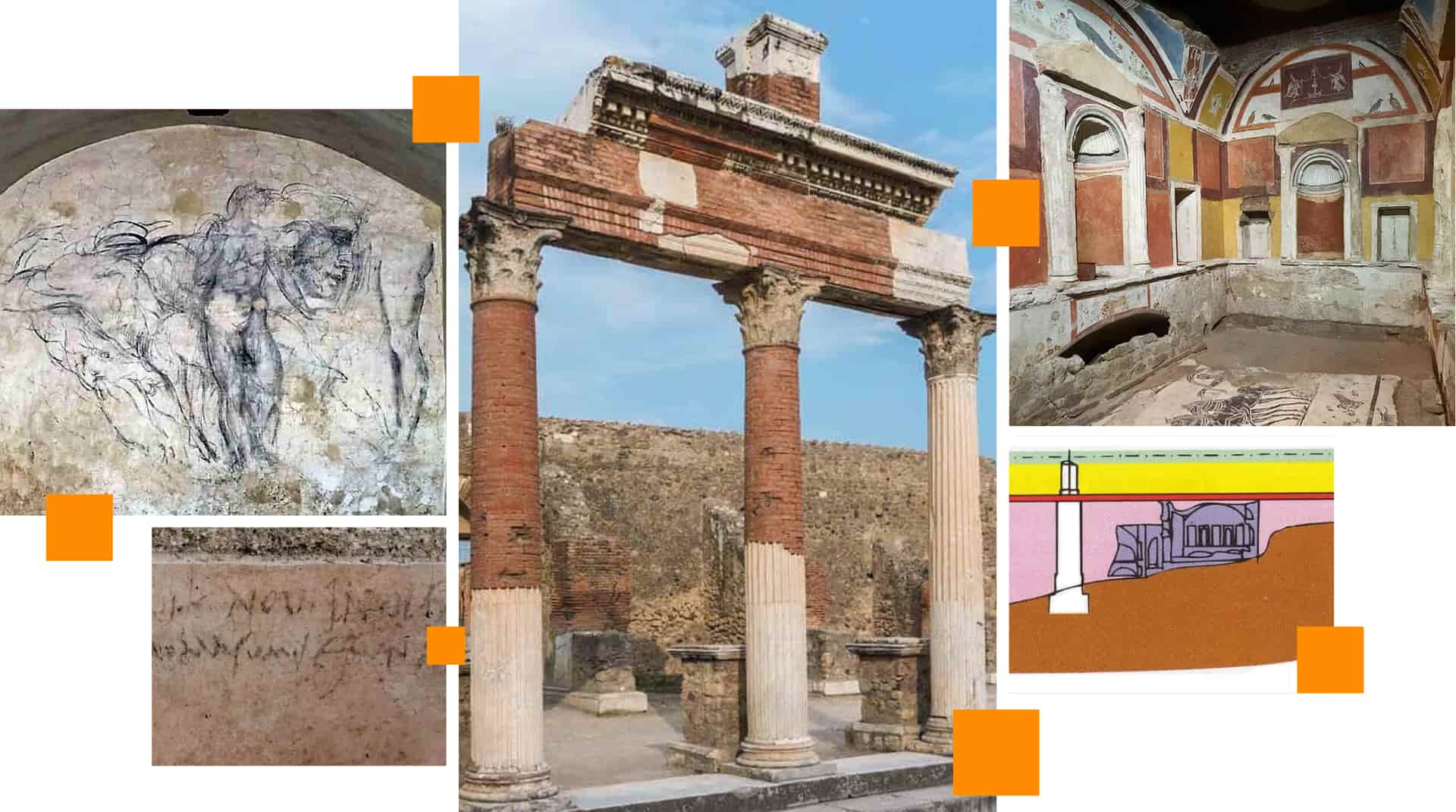

Shield with the head of Medusa

However, in Caravaggio’s artistic production there is a work that, while reproducing a severed head, does not coincide with the chronology of the painter’s post-conviction depiction obsession: the “shield with the head of Medusa”, an almost prophetic theme considering the date of its realisation. There are actually two versions of the shield, one begun in 1571 and known as the Medusa Murtola, and the second one, commissioned by Cardinal Del Monte for Ferdinando dè Medici, begun in 1598.

Being shields we are obviously talking about portable works and it is precisely the shape of the support that makes the result obtained in both cases by Caravaggio even more particular. The two works, although with different shades, have a green background, the elements of the head of Medusa, the only and undisputed protagonist of the work, despite some slight final chromatic difference, appear roughly the same.

Two versions of Medusa were created by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, one in 1596 and the other in 1597, depicting the exact moment she was executed by Perseus. © Public Domain

The first shield, also known as the Murtola wheel is a preparatory work for the perfect rendering of the second shield. This hypothesis would be confirmed by the fact that the preparatory drawing of the wheel was made in charcoal, precisely in order to be easily corrected to obtain the illusion of a concave base.

The study of these technicalities, which in many cases may seem sterile, are in this case fundamental because it is only through the perfect balance obtained between design and colour that Caravaggio was able to reproduce the effect of Perseus’s shield, shiny like a mirror.

Let’s not forget that Medusa, a mythological monster with a head covered with snakes, had the power to petrify anyone who looked into her eyes and it was only thanks to the image of the gorgon reflected on the shield that Perseus, protected by Minerva and Mercury, managed to kill her by chopping off her head.

Caravaggio did not depict the moment of the killing because that would have been perfect for a large canvas rather than for a shield, which conceptually had to simply recall the apotropaic value of the Medusa. Caravaggio decided to depict the precise, subtle and mysterious moment of the passage between life and death, the moment in which the amazement of the last breath gives way to elusive awareness of fear in the face of the mystery of death.

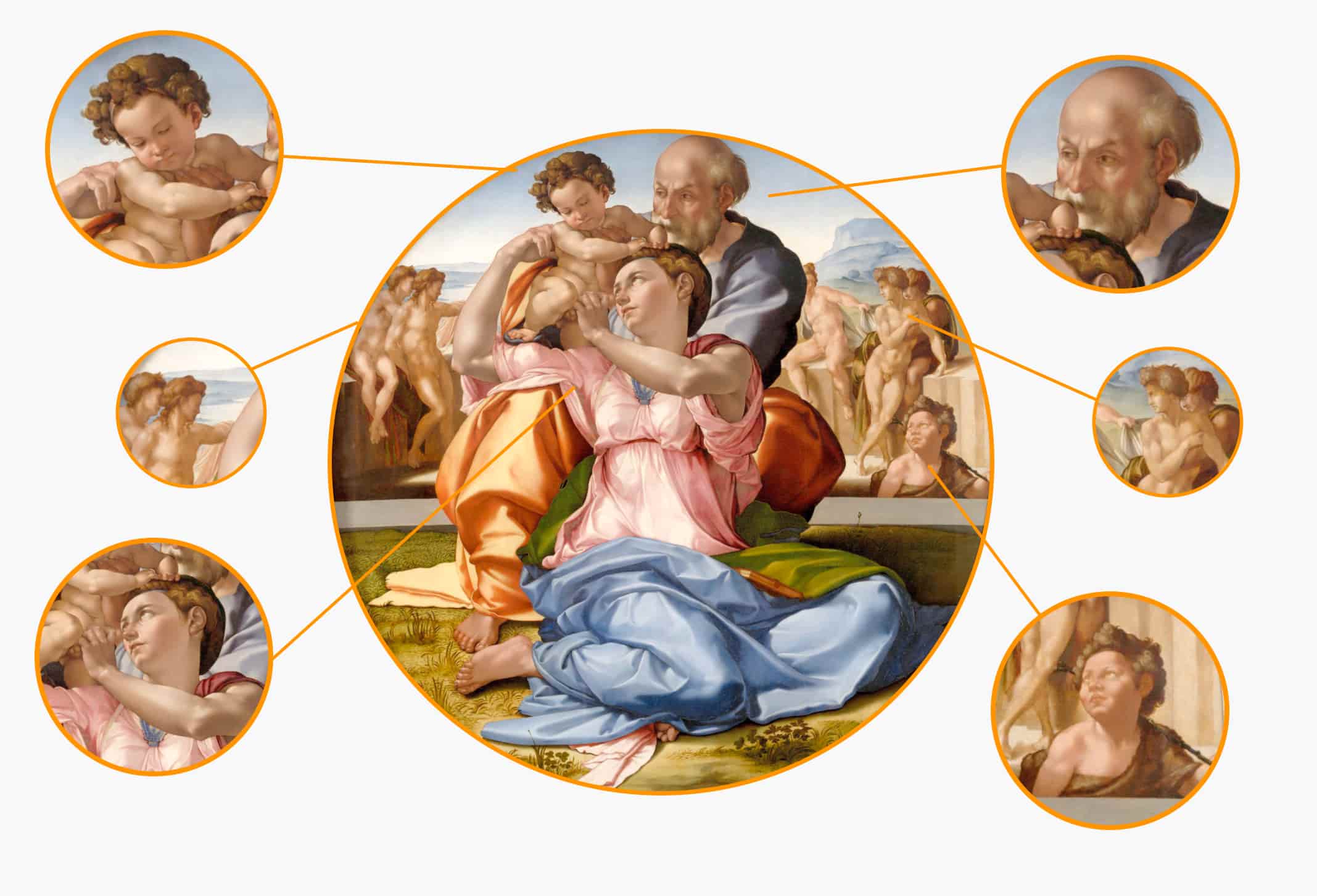

A name written in blood

Pain, fear and wonder, animate the head that is deprived of its body. It should no longer transmit any expression, any kind of feeling; instead just like the blood that comes out of Medusa’s severed head, so the human emotions that reside in the depths of the soul, continue to flow in those eyes once dispensers of death for those who looked at them.

Now, paradoxically, the head is still full of life, generating a scream, a pain that escapes from the mouth of Medusa and continues to resonate at first in the eyes, and then in the ears of the observer. The serpents making up her monstrous hair are still alive just like the gorgon’s head, and they perform sinuous movements that seem more real than realistic.

That scream, that frightened and crazy look that those who closely observe death have, are the scream and the look of Caravaggio. He painted himself on the head of Medusa and signed himself in the blood that comes out of the severed head with “Michelangelo fecit”. A latter formula that we will also find years later in the altarpiece of the “Slaughtered Baptist”, when the name Michelangelo and the fecit were imprinted again in the blood as if to seal a consecration, a complete belonging to art.